Lab 5: Bayesian models#

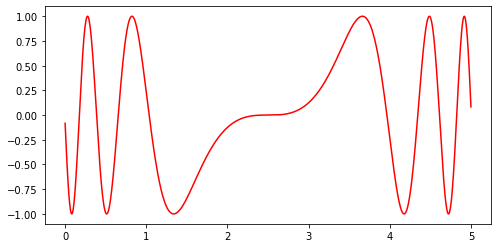

We will first learn a GP regressor for an artificial, non-linear function to illustrate some basic aspects of GPs. To this end, we consider a sinusoidal function from which we sample a dataset.

# General imports

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

The function to predict and the dataset we create from it:

def f(x):

"""The function to predict."""

return np.sin((x - 2.5) ** 3)

plt.figure(figsize=(8,4))

t = np.linspace(0,5,1000)

plt.plot(t, f(t), 'r', label = 'original f(x)')

[<matplotlib.lines.Line2D at 0x12d6a0580>]

The dataset we create based on the function:

# Dataset sampled from a sine function

rng = np.random.RandomState(4)

X_ = rng.uniform(0, 5, 1000)[:, np.newaxis]

y_ = f(X_).ravel()

def plot_gp(g, X_train, y_train, X_full, y_full, y_pred_mean, y_pred_std, use_title="yes"):

"""

Visualizes the GP predictions, training points and original function

Attributes:

X_train -- The training data

y_train -- The correct labels

X_full -- The data to calculate predictions

y_full -- The correct labels of the prediction data

y_pred_mean -- the predicted means

y_pred_std -- the predicted st. devs.

"""

x_ = np.linspace(0, 5, 1000)[:,np.newaxis]

idx = np.argsort(X_full[:,0])

# Original function

a = X_full[idx]

b = y_full[idx]

plt.figure(figsize=(8,4))

plt.plot(a,

b, 'r', label = 'original f(x)')

# Training points

plt.scatter(X_train, y_train, c='r', s=50, zorder=10, edgecolors=(0, 0, 0))

# Prediction

d = y_pred_mean[idx]

e = y_pred_std[idx]

plt.plot(a, d, 'k', lw=1, zorder=9)

plt.fill_between(a[:,0], d - 1.96*e, d + 1.96*e, alpha=0.2, color='k')

if use_title == "yes":

plt.title("Posterior (kernel: %s)\n Log-Likelihood: %.3f"

% (g.kernel_, g.log_marginal_likelihood(g.kernel_.theta)),

fontsize=12)

plt.tight_layout()

Exercise 1: visualizing predictions#

Train a GP regressor with a RBF kernel with default hyperparameters on a 1% sample of the sine data. Note that by learning a GP the hyperparameters of the chosen kernel are tuned automatically. To visualize what the GP has learned, use the model to predict values for the entire dataset. Plot the original function, the predictions and the training data points. You can use the function plot_gp() to assist with plotting.

Exercise 2: reducing the uncertainty#

Fit a model using 5% and 10% of the data. Now try setting n_restarts_optimizer in the GaussianProcessRegressor constructor. Plot the results. What differences do you see?

Exercise 3: Kernels#

Like SVMs, kernels play a major role in GPs. Using a 5% sample of the data, train one GP with each of the following kernels:

RBF

RationalQuadratic

ExpSineSquared

DotProduct

Matern

What differences do you see in the log-likelihood? Which model fit best the training data?

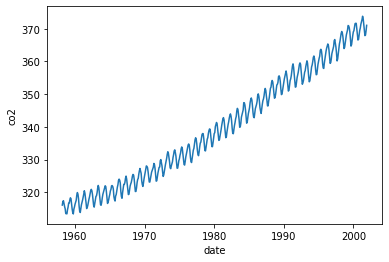

Exercise 4: Mauna Loa data#

We now look at the problem of predicting the monthly average CO2 concentrations collected at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, between 1958 and 2001. This is a time-series data.

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

# originally from sci-kit learn

def load_mauna_loa_atmospheric_co2():

ml_data = fetch_openml(data_id=41187, as_frame=False)

months = []

ppmv_sums = []

counts = []

y = ml_data.data[:, 0]

m = ml_data.data[:, 1]

month_float = y + (m - 1) / 12

ppmvs = ml_data.target

for month, ppmv in zip(month_float, ppmvs):

if not months or month != months[-1]:

months.append(month)

ppmv_sums.append(ppmv)

counts.append(1)

else:

# aggregate monthly sum to produce average

ppmv_sums[-1] += ppmv

counts[-1] += 1

months = np.asarray(months).reshape(-1, 1)

avg_ppmvs = np.asarray(ppmv_sums) / counts

return months, avg_ppmvs

X_mauna, y_mauna = load_mauna_loa_atmospheric_co2()

Quick visualization:

#Quick visualization

plt.plot(X_mauna,y_mauna)

plt.xlabel('date')

plt.ylabel('co2')

Text(0, 0.5, 'co2')

Exercise 4.1#

Signals like this usually consist of a combination of different “sub-signals”, e.g. a long-term component, a seasonal component, a noise component, and so on. When defining a GP kernel, you can combine multiple kernels, such as:

A RBF kernel can be used to explain long-term, smooth patterns.

The seasonal component can be modeled by an

ExpSineSquaredcomponent.Small and medium-term irregularities can be modeled by a

RationalQuadraticcomponent.WhiteNoisekernel to model white noise.

Train a GP using the first 75% data points as training data using the kernel below. Experiment with removing one or more kernels and check the results visually (you can use plot_gp). What do you observe?

from sklearn.gaussian_process.kernels import WhiteKernel, RBF, ExpSineSquared, RationalQuadratic

k1 = 50.0**2 * RBF(length_scale=50.0) # long term smooth rising trend

k2 = 2.0**2 * RBF(length_scale=100.0) \

* ExpSineSquared(length_scale=1.0, periodicity=1.0,

periodicity_bounds="fixed") # seasonal component

# medium term irregularities

k3 = 0.5**2 * RationalQuadratic(length_scale=1.0, alpha=1.0)

k4 = 0.1**2 * RBF(length_scale=0.1) \

+ WhiteKernel(noise_level=0.1**2,

noise_level_bounds=(1e-5, np.inf)) # noise terms

kernel = k1 + k2 + k3 + k4