Can I trust you?

Joaquin Vanschoren

Source

# Auto-setup when running on Google Colab

import os

if 'google.colab' in str(get_ipython()) and not os.path.exists('/content/master'):

!git clone -q https://github.com/ML-course/master.git /content/master

!pip --quiet install -r /content/master/requirements_colab.txt

%cd master/notebooks

# Global imports and settings

%matplotlib inline

from preamble import *

interactive = False # Set to True for interactive plots

if interactive:

fig_scale = 0.5

plt.rcParams.update(print_config)

else:

fig_scale = 1.25Evaluation¶

To know whether we can trust our method or system, we need to evaluate it.

Model selection: choose between different models in a data-driven way.

If you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it.

Convince others that your work is meaningful

Peers, leadership, clients, yourself(!)

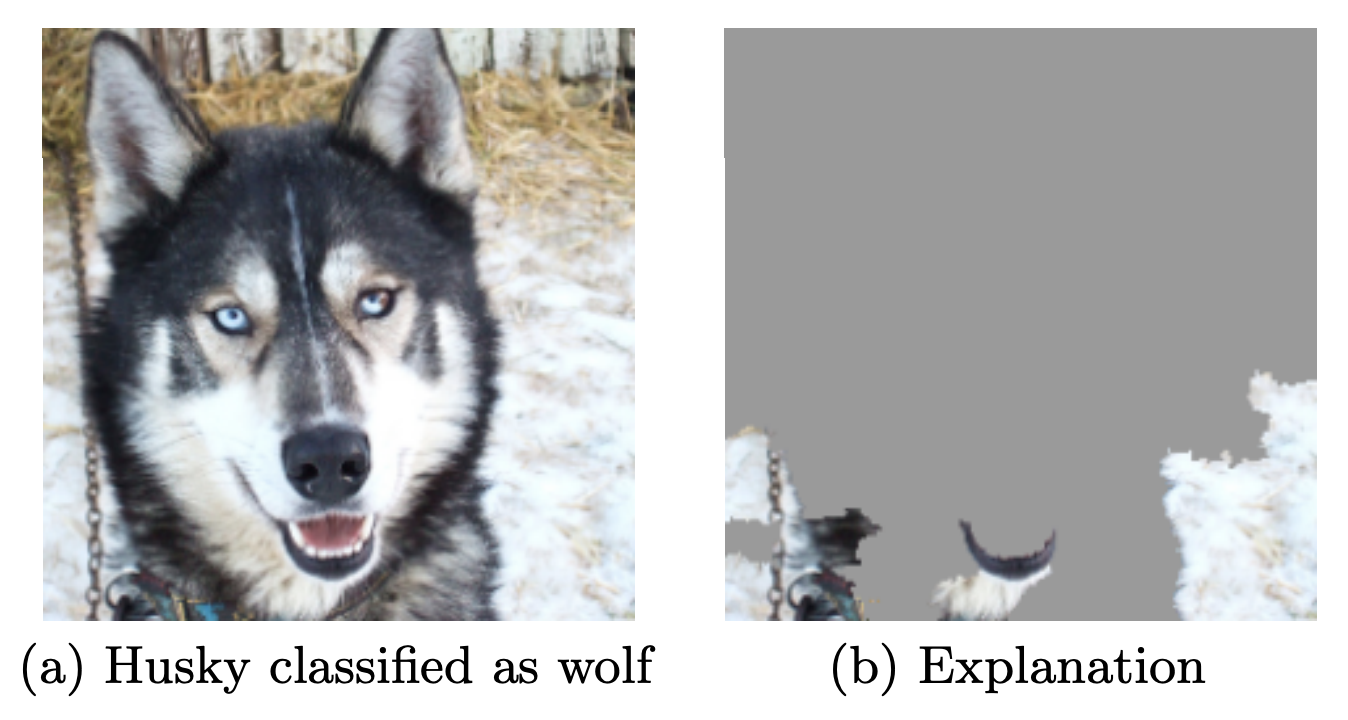

When possible, try to interpret what your model has learned

The signal your model found may just be an artifact of your biased data

See ‘Why Should I Trust You?’ by Marco Ribeiro et al.

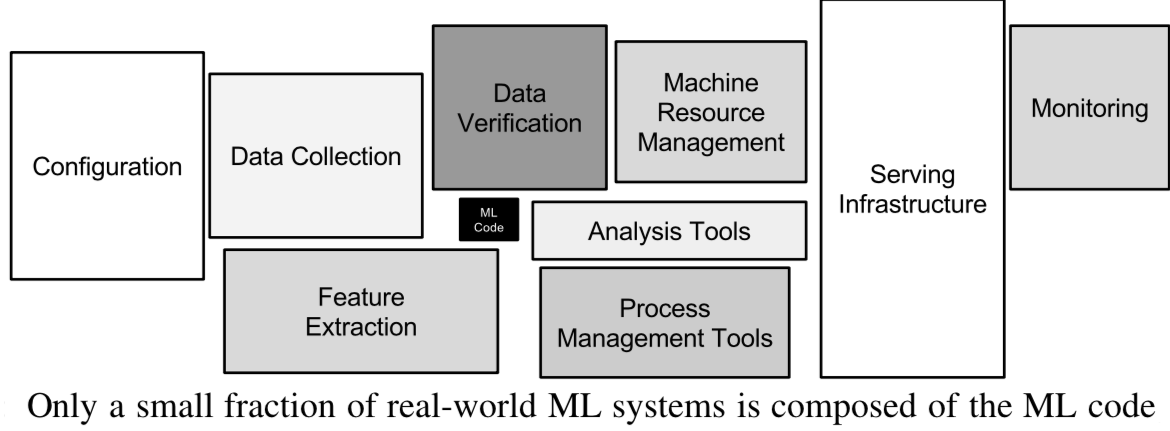

Designing Machine Learning systems¶

Just running your favourite algorithm is usually not a great way to start

Consider the problem: How to measure success? Are there costs involved?

Do you want to understand phenomena or do black box modelling?

Analyze your model’s mistakes. Don’t just finetune endlessly.

Build early prototypes. Should you collect more, or additional data?

Should the task be reformulated?

Overly complex machine learning systems are hard to maintain

See ‘Machine Learning: The High Interest Credit Card of Technical Debt’

Real world evaluations¶

Evaluate predictions, but also how outcomes improve because of them

Beware of feedback loops: predictions can influence future input data

Medical recommendations, spam filtering, trading algorithms,...

Evaluate algorithms in the wild.

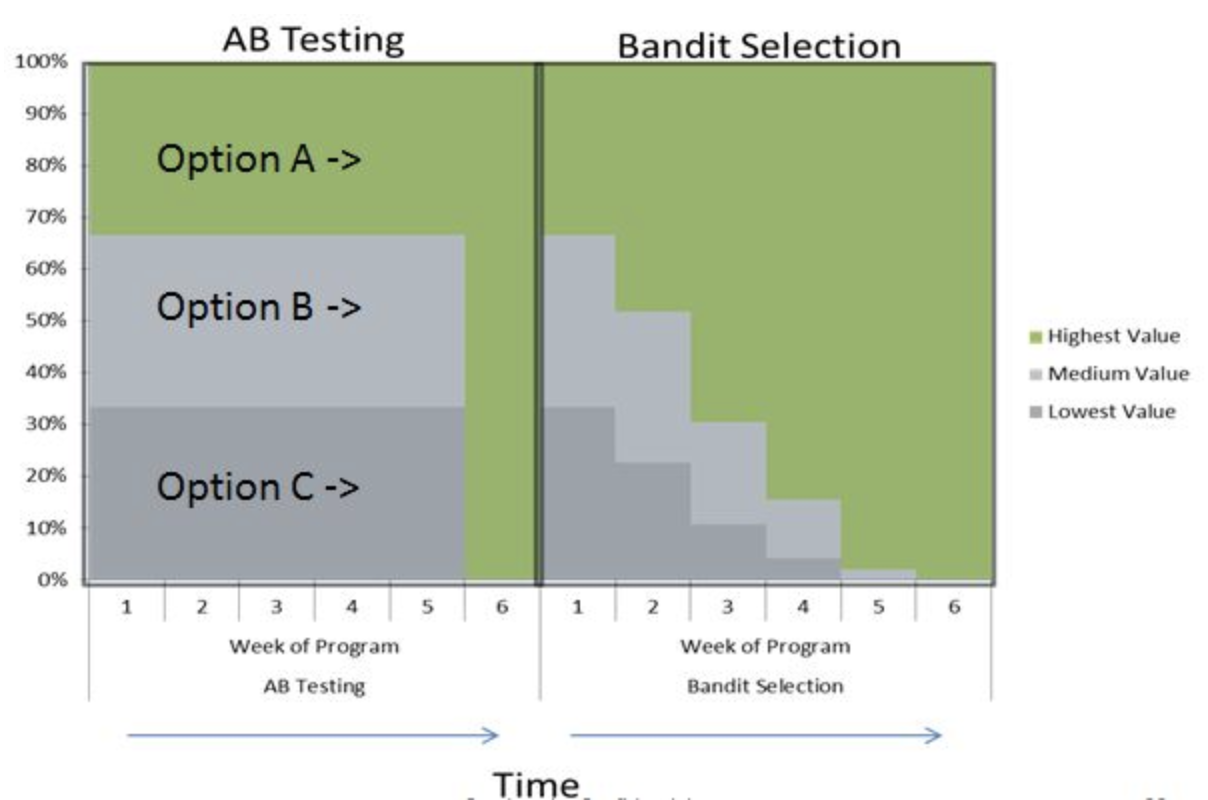

A/B testing: split users in groups, test different models in parallel

Bandit testing: gradually direct more users to the winning system

Performance estimation techniques¶

Always evaluate models as if they are predicting future data

We do not have access to future data, so we pretend that some data is hidden

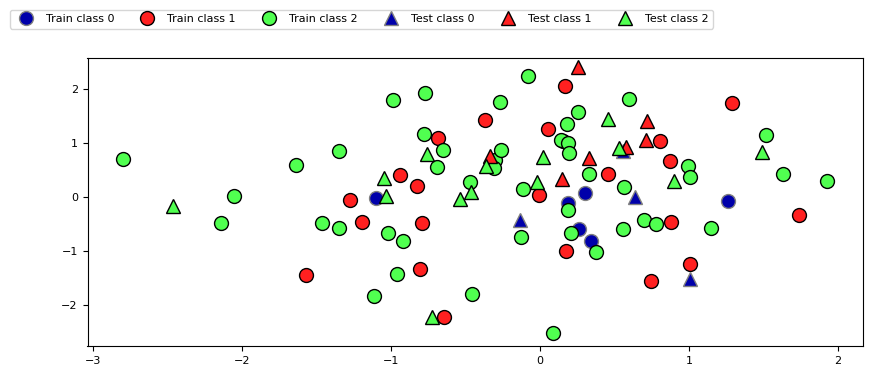

Simplest way: the holdout (simple train-test split)

Randomly split data (and corresponding labels) into training and test set (e.g. 75%-25%)

Train (fit) a model on the training data, score on the test data

Source

from sklearn.model_selection import (TimeSeriesSplit, KFold, ShuffleSplit, train_test_split,

StratifiedKFold, GroupShuffleSplit,

GroupKFold, StratifiedShuffleSplit)

from matplotlib.patches import Patch

np.random.seed(1338)

cmap_data = plt.cm.brg

cmap_group = plt.cm.Paired

cmap_cv = plt.cm.coolwarm

n_splits = 4

# Generate the class/group data

n_points = 100

X = np.random.randn(100, 10)

percentiles_classes = [.1, .3, .6]

y = np.hstack([[ii] * int(100 * perc)

for ii, perc in enumerate(percentiles_classes)])

# Evenly spaced groups repeated once

rng = np.random.RandomState(42)

group_prior = rng.dirichlet([2]*10)

rng.multinomial(100, group_prior)

groups = np.repeat(np.arange(10), rng.multinomial(100, group_prior))Source

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, random_state=0)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X_train[:, 0], X_train[:, 1], y_train,

markers='o', ax=ax)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X_test[:, 0], X_test[:, 1], y_test,

markers='^', ax=ax)

ax.legend(["Train class 0", "Train class 1", "Train class 2", "Test class 0",

"Test class 1", "Test class 2"], ncol=6, loc=(-0.1, 1.1));

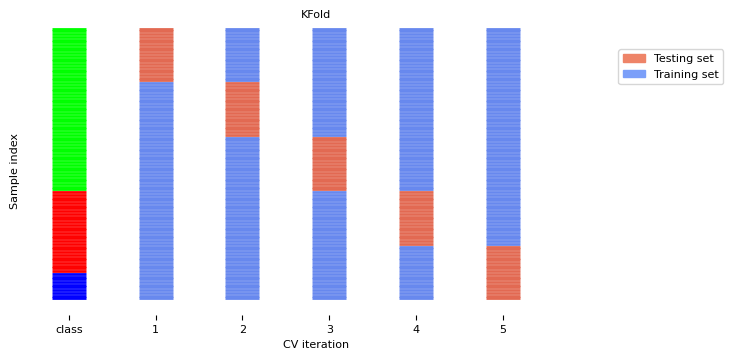

K-fold Cross-validation¶

Each random split can yield very different models (and scores)

e.g. all easy (of hard) examples could end up in the test set

Split data into k equal-sized parts, called folds

Create k splits, each time using a different fold as the test set

Compute k evaluation scores, aggregate afterwards (e.g. take the mean)

Examine the score variance to see how sensitive (unstable) models are

Large k gives better estimates (more training data), but is expensive

Source

def plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, group, ax, lw=2, show_groups=False, s=700, legend=True):

"""Create a sample plot for indices of a cross-validation object."""

n_splits = cv.get_n_splits(X, y, group)

# Generate the training/testing visualizations for each CV split

for ii, (tr, tt) in enumerate(cv.split(X=X, y=y, groups=group)):

# Fill in indices with the training/test groups

indices = np.array([np.nan] * len(X))

indices[tt] = 1

indices[tr] = 0

# Visualize the results

ax.scatter([n_splits - ii - 1] * len(indices), range(len(indices)),

c=indices, marker='_', lw=lw, cmap=cmap_cv,

vmin=-.2, vmax=1.2, s=s)

# Plot the data classes and groups at the end

ax.scatter([-1] * len(X), range(len(X)),

c=y, marker='_', lw=lw, cmap=cmap_data, s=s)

yticklabels = ['class'] + list(range(1, n_splits + 1))

if show_groups:

ax.scatter([-2] * len(X), range(len(X)),

c=group, marker='_', lw=lw, cmap=cmap_group, s=s)

yticklabels.insert(0, 'group')

# Formatting

ax.set(xticks=np.arange(-1 - show_groups, n_splits), xticklabels=yticklabels,

ylabel='Sample index', xlabel="CV iteration",

xlim=[-1.5 - show_groups, n_splits+.2], ylim=[-6, 100])

ax.set_title('{}'.format(type(cv).__name__), fontsize=8)

if legend:

ax.legend([Patch(color=cmap_cv(.8)), Patch(color=cmap_cv(.2))],

['Testing set', 'Training set'], loc=(1.02, .8))

ax.spines['top'].set_visible(False)

ax.spines['right'].set_visible(False)

ax.spines['left'].set_visible(False)

ax.spines['bottom'].set_visible(False)

ax.set_yticks(())

return axSource

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = KFold(5)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, s=600);

Can you explain this result?

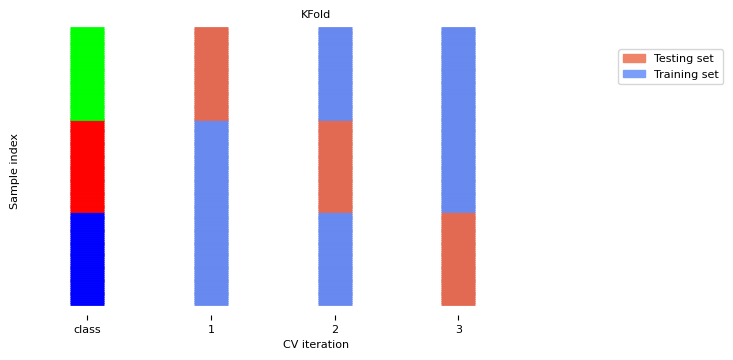

kfold = KFold(n_splits=3)

cross_val_score(logistic_regression, iris.data, iris.target, cv=kfold)Source

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold, StratifiedKFold, cross_val_score

from sklearn.datasets import load_iris

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

iris = load_iris()

logreg = LogisticRegression()

kfold = KFold(n_splits=3)

print("Cross-validation scores KFold(n_splits=3):\n{}".format(

cross_val_score(logreg, iris.data, iris.target, cv=kfold)))Cross-validation scores KFold(n_splits=3):

[0. 0. 0.]

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

plot_cv_indices(kfold, iris.data, iris.target, iris.target, ax, s=600)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 150));

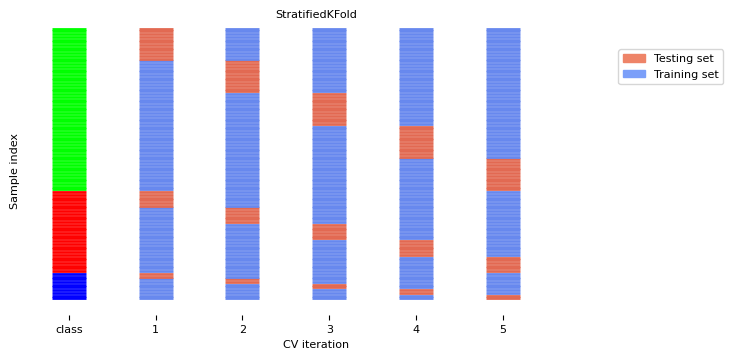

Stratified K-Fold cross-validation¶

If the data is unbalanced, some classes have only few samples

Likely that some classes are not present in the test set

Stratification: proportions between classes are conserved in each fold

Order examples per class

Separate the samples of each class in k sets (strata)

Combine corresponding strata into folds

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = StratifiedKFold(5)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, s=600)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100));

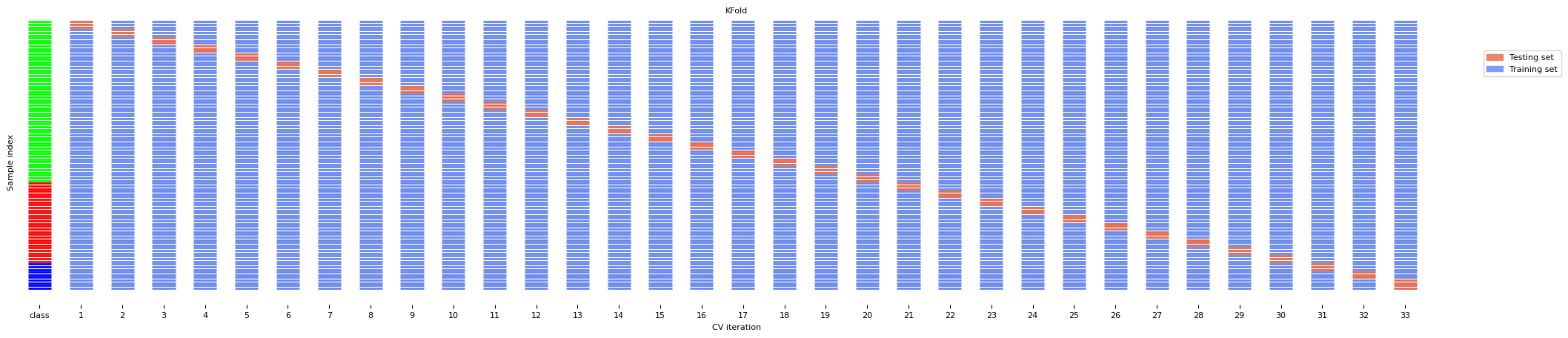

Leave-One-Out cross-validation¶

k fold cross-validation with k equal to the number of samples

Completely unbiased (in terms of data splits), but computationally expensive

Actually generalizes less well towards unseen data

The training sets are correlated (overlap heavily)

Overfits on the data used for (the entire) evaluation

A different sample of the data can yield different results

Recommended only for small datasets

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(20*fig_scale, 4*fig_scale))

cv = KFold(33) # There are more than 33 classes, but this visualizes better.

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, s=500)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100));

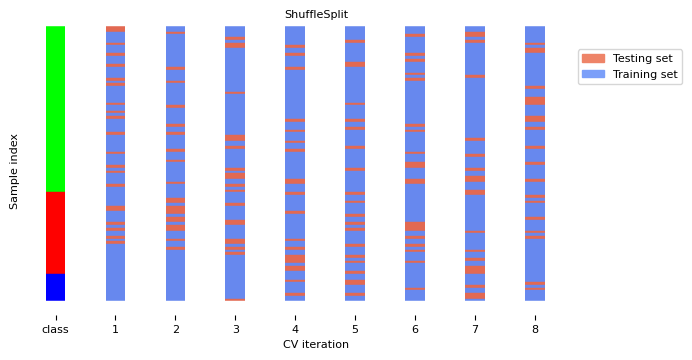

Shuffle-Split cross-validation¶

Shuffles the data, samples (

train_size) points randomly as the training setCan also use a smaller (

test_size), handy with very large datasetsNever use if the data is ordered (e.g. time series)

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = ShuffleSplit(8, test_size=.2)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, n_splits, s=200)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100))

ax.legend([Patch(color=cmap_cv(.8)), Patch(color=cmap_cv(.2))],

['Testing set', 'Training set'], loc=(.95, .8));

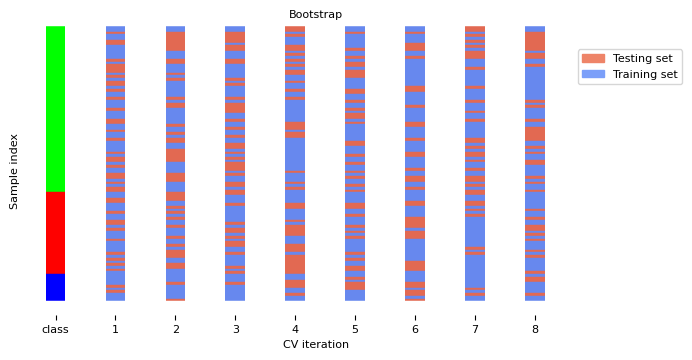

The Bootstrap¶

Sample n (dataset size) data points, with replacement, as training set (the bootstrap)

On average, bootstraps include 66% of all data points (some are duplicates)

Use the unsampled (out-of-bootstrap) samples as the test set

Repeat times to obtain scores

Similar to Shuffle-Split with

train_size=0.66,test_size=0.34but without duplicates

Source

from sklearn.utils import resample

# Toy implementation of bootstrapping

class Bootstrap:

def __init__(self, nr):

self.nr = nr

def get_n_splits(self, X, y, groups=None):

return self.nr

def split(self, X, y, groups=None):

indices = range(len(X))

splits = []

for i in range(self.nr):

train = resample(indices, replace=True, n_samples=len(X), random_state=i)

test = list(set(indices) - set(train))

splits.append((train, test))

return splits

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = Bootstrap(8)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, n_splits, s=200)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100))

ax.legend([Patch(color=cmap_cv(.8)), Patch(color=cmap_cv(.2))],

['Testing set', 'Training set'], loc=(.95, .8));

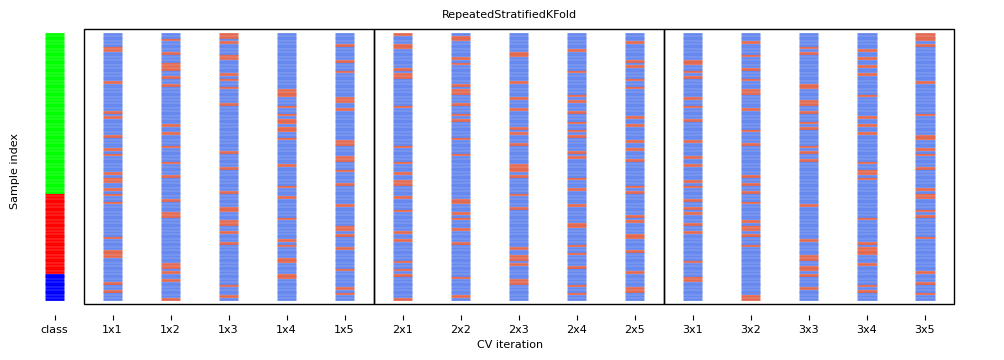

Repeated cross-validation¶

Cross-validation is still biased in that the initial split can be made in many ways

Repeated, or n-times-k-fold cross-validation:

Shuffle data randomly, do k-fold cross-validation

Repeat n times, yields n times k scores

Unbiased, very robust, but n times more expensive

Source

from sklearn.model_selection import RepeatedStratifiedKFold

from matplotlib.patches import Rectangle

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = RepeatedStratifiedKFold(n_splits=5, n_repeats=3)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, lw=2, s=200, legend=False)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 102))

xticklabels = ["class"] + [f"{repeat}x{split}" for repeat in range(1, 4) for split in range(1, 6)]

ax.set_xticklabels(xticklabels)

for i in range(3):

rect = Rectangle((-.5 + i * 5, -2.), 5, 103, edgecolor='k', facecolor='none')

ax.add_artist(rect)

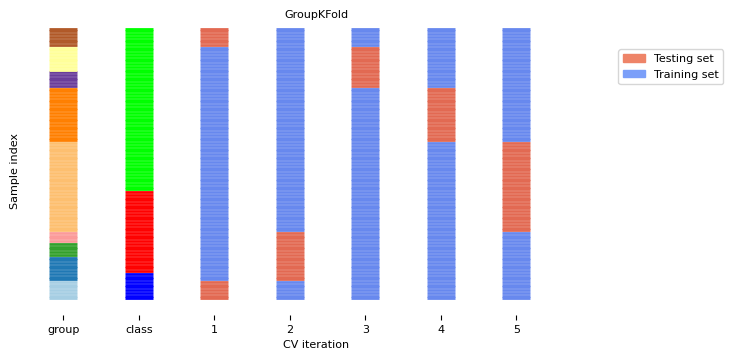

Cross-validation with groups¶

Sometimes the data contains inherent groups:

Multiple samples from same patient, images from same person,...

Data from the same person may end up in the training and test set

We want to measure how well the model generalizes to other people

Make sure that data from one person are in either the train or test set

This is called grouping or blocking

Leave-one-subject-out cross-validation: test set for each subject/group

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = GroupKFold(5)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, y, groups, ax, s=400, show_groups=True)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100));

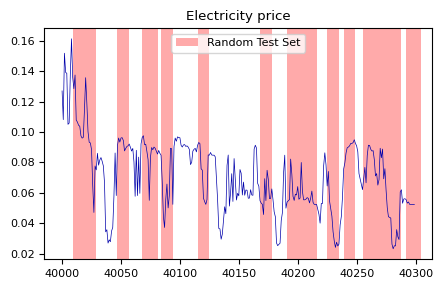

Time series¶

When the data is ordered, random test sets are not a good idea

Source

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

electricity_data = fetch_openml(name="electricity", as_frame=True)

X_C, y_C = electricity_data.data, electricity_data.target

X_C = X_C.iloc[40000:40300]

X_C.nswprice.plot()

ax = plt.gca()

plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (12*fig_scale,6*fig_scale)

ax.set_xlabel("")

xlim, ylim = ax.get_xlim(), ax.get_ylim()

for i in range(20):

rect = Rectangle((np.random.randint(40000, xlim[1]), ylim[0]), 10, ylim[1]-ylim[0], facecolor='#FFAAAA')

ax.add_artist(rect)

plt.title("Electricity price")

plt.legend([rect], ['Random Test Set'] );

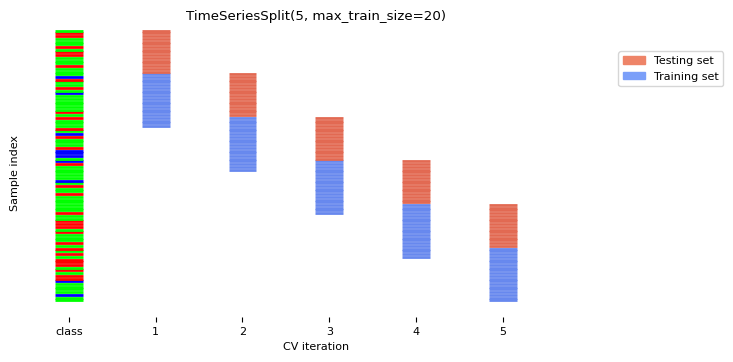

Test-then-train (prequential evaluation)¶

Every new sample is evaluated only once, then added to the training set

Can also be done in batches (of n samples at a time)

TimeSeriesSplitIn the kth split, the first k folds are the train set and the (k+1)th fold as the test set

Often, a maximum training set size (or window) is used

more robust against concept drift (change in data over time)

Source

from sklearn.utils import shuffle

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

cv = TimeSeriesSplit(5, max_train_size=20)

plot_cv_indices(cv, X, shuffle(y), groups, ax, s=400, lw=2)

ax.set_ylim((-6, 100))

ax.set_title("TimeSeriesSplit(5, max_train_size=20)");

Choosing a performance estimation procedure¶

No strict rules, only guidelines:

Always use stratification for classification (sklearn does this by default)

Use holdout for very large datasets (e.g. >1.000.000 examples)

Or when learners don’t always converge (e.g. deep learning)

Choose k depending on dataset size and resources

Use leave-one-out for very small datasets (e.g. <100 examples)

Use cross-validation otherwise

Most popular (and theoretically sound): 10-fold CV

Literature suggests 5x2-fold CV is better

Use grouping or leave-one-subject-out for grouped data

Use train-then-test for time series

Evaluation Metrics for Classification¶

Evaluation vs Optimization¶

Each algorithm optimizes a given objective function (on the training data)

E.g. remember L2 loss in Ridge regression

The choice of function is limited by what can be efficiently optimized

However, we evaluate the resulting model with a score that makes sense in the real world

Percentage of correct predictions (on a test set)

The actual cost of mistakes (e.g. in money, time, lives,...)

We also tune the algorithm’s hyperparameters to maximize that score

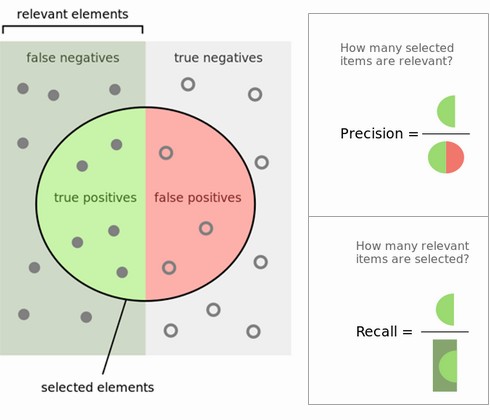

Binary classification¶

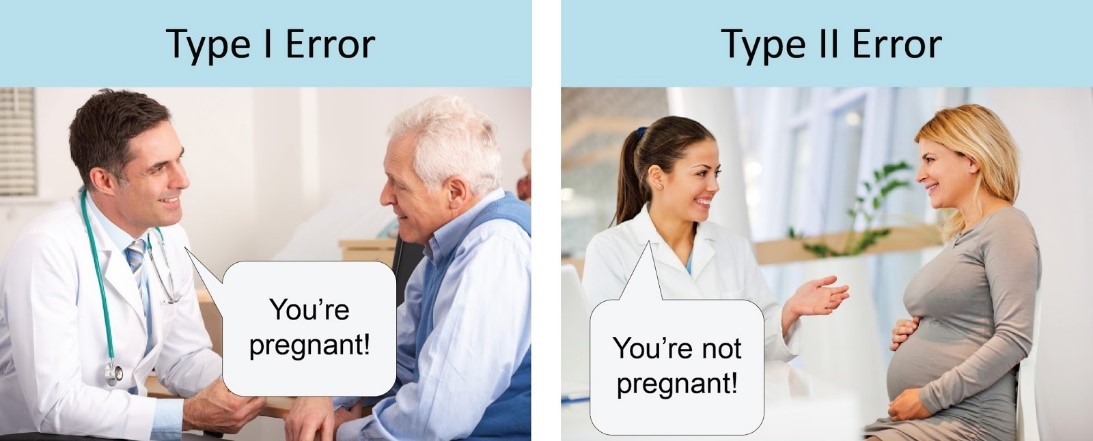

We have a positive and a negative class

2 different kind of errors:

False Positive (type I error): model predicts positive while true label is negative

False Negative (type II error): model predicts negative while true label is positive

They are not always equally important

Which side do you want to err on for a medical test?

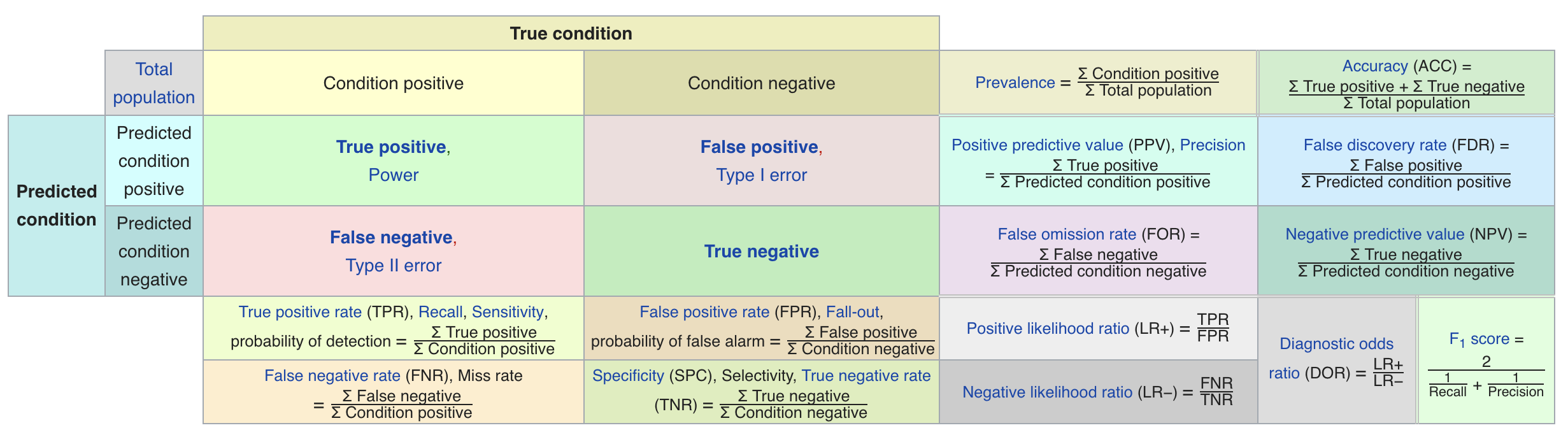

Confusion matrices¶

We can represent all predictions (correct and incorrect) in a confusion matrix

n by n array (n is the number of classes)

Rows correspond to true classes, columns to predicted classes

Count how often samples belonging to a class C are classified as C or any other class.

For binary classification, we label these true negative (TN), true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP)

| Predicted Neg | Predicted Pos | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Neg | TN | FP |

| Actual Pos | FN | TP |

Source

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score, confusion_matrix

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

data = load_breast_cancer()

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

data.data, data.target, stratify=data.target, random_state=0)

lr = LogisticRegression().fit(X_train, y_train)

y_pred = lr.predict(X_test)

print("confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred): \n", confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred))confusion_matrix(y_test, y_pred):

[[49 4]

[ 5 85]]

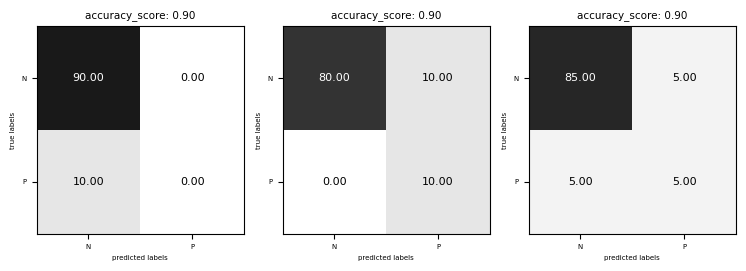

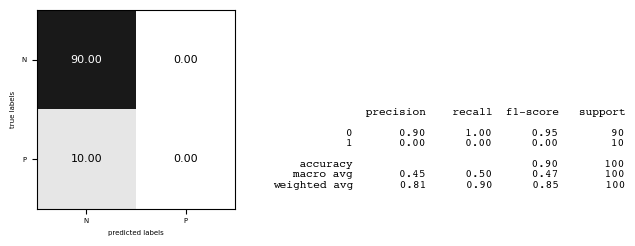

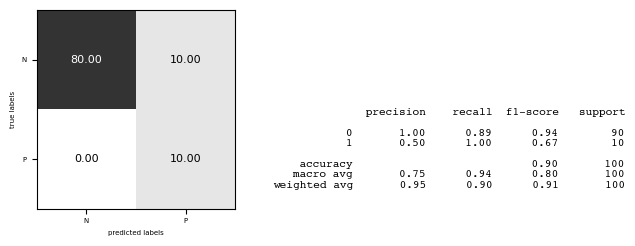

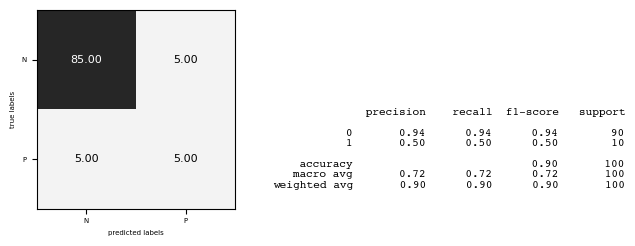

Predictive accuracy¶

Accuracy can be computed based on the confusion matrix

Not useful if the dataset is very imbalanced

E.g. credit card fraud: is 99.99% accuracy good enough?

3 models: very different predictions, same accuracy:

def plot_confusion_matrix(values, xlabel="predicted labels", ylabel="true labels", xticklabels=None,

yticklabels=None, cmap=None, vmin=None, vmax=None, ax=None,

fmt="{:.2f}", xtickrotation=45, norm=None, fsize=8):

if ax is None:

ax = plt.gca()

ax.figure.set_size_inches(6*fig_scale, 6*fig_scale)

values = np.array(values) # Ensure 'values' is a numpy array for consistent handling

img = ax.pcolormesh(values, cmap=cmap, vmin=vmin, vmax=vmax, norm=norm)

ax.set_xlabel(xlabel, fontsize=5)

ax.set_ylabel(ylabel, fontsize=5)

# Setting the tick labels

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(values.shape[1]) + 0.5, minor=False)

ax.set_yticks(np.arange(values.shape[0]) + 0.5, minor=False)

ax.set_xticklabels(xticklabels or [], minor=False, rotation=xtickrotation, fontsize=5)

ax.set_yticklabels(yticklabels or [], minor=False, fontsize=5)

# Loop over data dimensions and create text annotations.

for i in range(values.shape[0]):

for j in range(values.shape[1]):

ax.text(j + 0.5, i + 0.5, fmt.format(values[i, j]),

ha="center", va="center", color="white" if values[i, j] > vmax/2 else "black", fontsize=8)

ax.set_aspect('equal') # Optional: set aspect ratio to be equal

ax.invert_yaxis()

return axSource

# Artificial 90-10 imbalanced target

y_true = np.zeros(100, dtype=int)

y_true[:10] = 1

y_pred_1 = np.zeros(100, dtype=int)

y_pred_2 = y_true.copy()

y_pred_2[10:20] = 1

y_pred_3 = y_true.copy()

y_pred_3[5:15] = 1 - y_pred_3[5:15]

def plot_measure(measure):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3)

for i, (ax, y_pred) in enumerate(zip(axes, [y_pred_1, y_pred_2, y_pred_3])):

plot_confusion_matrix(confusion_matrix(y_true, y_pred), cmap='gray_r', ax=ax,

xticklabels=["N", "P"], yticklabels=["N", "P"], xtickrotation=0, vmin=0, vmax=100)

ax.set_title("{}: {:.2f}".format(measure.__name__,measure(y_true, y_pred)), fontsize=6*fig_scale)

plt.tight_layout()Source

plot_measure(accuracy_score)

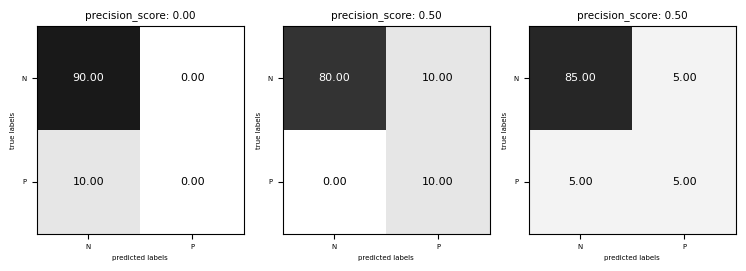

Precision¶

Use when the goal is to limit FPs

Clinical trails: you only want to test drugs that really work

Search engines: you want to avoid bad search results

Source

from sklearn.metrics import precision_score

plot_measure(precision_score)

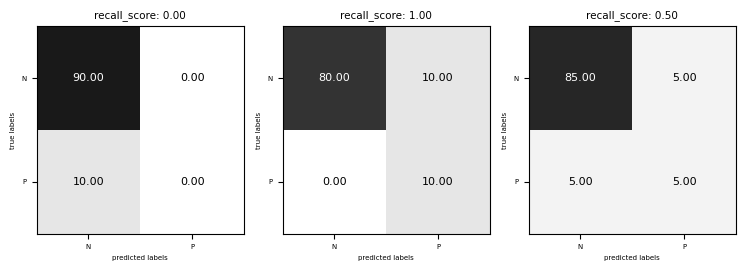

Recall¶

Use when the goal is to limit FNs

Cancer diagnosis: you don’t want to miss a serious disease

Search engines: You don’t want to omit important hits

Also know as sensitivity, hit rate, true positive rate (TPR)

Source

from sklearn.metrics import recall_score

plot_measure(recall_score)

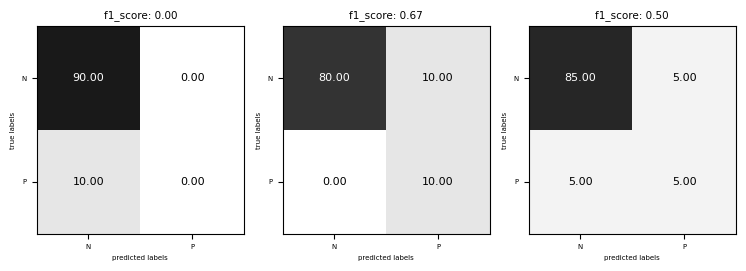

Comparison

Source

from sklearn.metrics import f1_score

plot_measure(f1_score)

Classification measure Zoo

Multi-class classification¶

Train models per class : one class viewed as positive, other(s) als negative, then average

micro-averaging: count total TP, FP, TN, FN (every sample equally important)

micro-precision, micro-recall, micro-F1, accuracy are all the same

macro-averaging: average of scores obtained on each class

Preferable for imbalanced classes (if all classes are equally important)

macro-averaged recall is also called balanced accuracy

weighted averaging (: ratio of examples of class , aka support):

Source

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

def report(y_pred):

fig = plt.figure()

ax = plt.subplot(111)

plot_confusion_matrix(confusion_matrix(y_true, y_pred), cmap='gray_r', ax=ax,

xticklabels=["N", "P"], yticklabels=["N", "P"], xtickrotation=0, vmin=0, vmax=100, fsize=2.5)

ax.figure.set_size_inches(2*fig_scale, 2*fig_scale)

plt.gcf().text(1.1, 0.2, classification_report(y_true, y_pred), fontsize=8, fontname="Courier")

plt.tight_layout()

report(y_pred_1)

report(y_pred_2)

report(y_pred_3)

Other useful classification metrics¶

Cohen’s Kappa

Measures ‘agreement’ between different models (aka inter-rater agreement)

To evaluate a single model, compare it against a model that does random guessing

Similar to accuracy, but taking into account the possibility of predicting the right class by chance

Can be weighted: different misclassifications given different weights

1: perfect prediction, 0: random prediction, negative: worse than random

With = accuracy, and = accuracy of random classifier:

Matthews correlation coefficient

Corrects for imbalanced data, alternative for balanced accuracy or AUROC

1: perfect prediction, 0: random prediction, -1: inverse prediction

Probabilistic evaluation¶

Classifiers can often provide uncertainty estimates of predictions.

Remember that linear models actually return a numeric value.

When , predict class -1, otherwise predict class +1

In practice, you are often interested in how certain a classifier is about each class prediction (e.g. cancer treatments).

Most learning methods can return at least one measure of confidence in their predicions.

Decision function: floating point value for each sample (higher: more confident)

Probability: estimated probability for each class

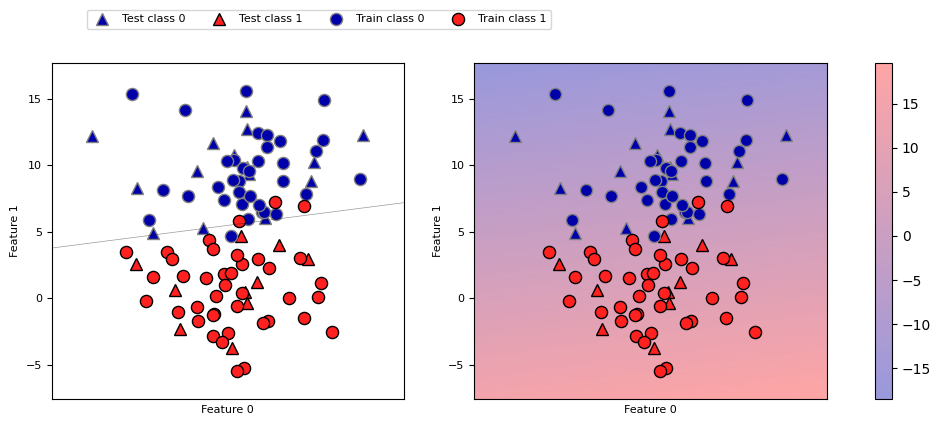

The decision function¶

In the binary classification case, the return value of the decision function encodes how strongly the model believes a data point belongs to the “positive” class.

Positive values indicate preference for the positive class.

The range can be arbitrary, and can be affected by hyperparameters. Hard to interpret.

Source

# create and split a synthetic dataset

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

Xs, ys = make_blobs(centers=2, cluster_std=2.5, random_state=8)

# we rename the classes "blue" and "red"

ys_named = np.array(["blue", "red"])[ys]

# we can call train test split with arbitrary many arrays

# all will be split in a consistent manner

Xs_train, Xs_test, ys_train_named, ys_test_named, ys_train, ys_test = \

train_test_split(Xs, ys_named, ys, random_state=0)

# build the logistic regression model

lr = LogisticRegression()

lr.fit(Xs_train, ys_train_named)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10*fig_scale, 3.5*fig_scale))

mglearn.tools.plot_2d_separator(lr, Xs, ax=axes[0], alpha=.4,

fill=False, cm=mglearn.cm2)

scores_image = mglearn.tools.plot_2d_scores(lr, Xs, ax=axes[1],

alpha=.4, cm=mglearn.ReBl)

for ax in axes:

# plot training and test points

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xs_test[:, 0], Xs_test[:, 1], ys_test,

markers='^', ax=ax, s=7*fig_scale)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xs_train[:, 0], Xs_train[:, 1], ys_train,

markers='o', ax=ax, s=7*fig_scale)

ax.set_xlabel("Feature 0")

ax.set_ylabel("Feature 1")

cbar = plt.colorbar(scores_image, ax=axes.tolist())

cbar.set_alpha(1)

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=8*fig_scale)

axes[0].legend(["Test class 0", "Test class 1", "Train class 0",

"Train class 1"], ncol=4, loc=(.1, 1.1));

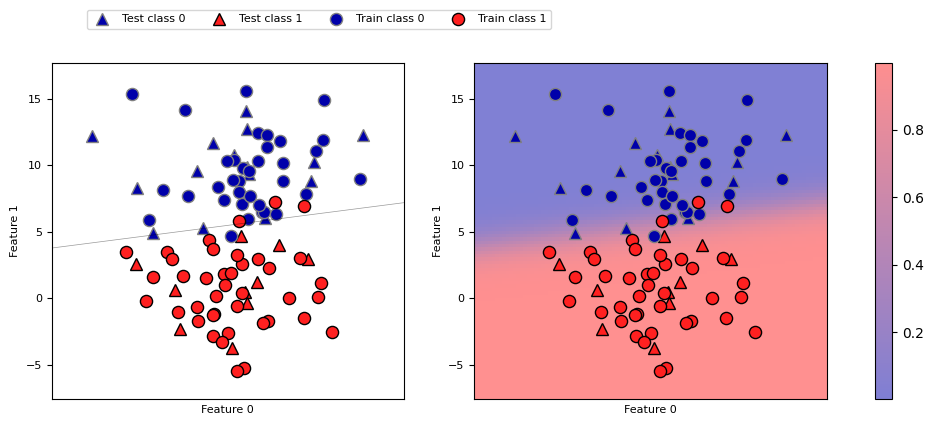

Predicting probabilities¶

Some models can also return a probability for each class with every prediction. These sum up to 1. We can visualize them again. Note that the gradient looks different now.

Source

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10*fig_scale, 3.5*fig_scale))

mglearn.tools.plot_2d_separator(

lr, Xs, ax=axes[0], alpha=.4, fill=False, cm=mglearn.cm2)

scores_image = mglearn.tools.plot_2d_scores(

lr, Xs, ax=axes[1], alpha=.5, cm=mglearn.ReBl, function='predict_proba')

for ax in axes:

# plot training and test points

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xs_test[:, 0], Xs_test[:, 1], ys_test,

markers='^', ax=ax, s=7*fig_scale)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xs_train[:, 0], Xs_train[:, 1], ys_train,

markers='o', ax=ax, s=7*fig_scale)

ax.set_xlabel("Feature 0")

ax.set_ylabel("Feature 1")

# don't want a transparent colorbar

cbar = plt.colorbar(scores_image, ax=axes.tolist())

cbar.set_alpha(1)

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=8*fig_scale)

axes[0].legend(["Test class 0", "Test class 1", "Train class 0",

"Train class 1"], ncol=4, loc=(.1, 1.1));

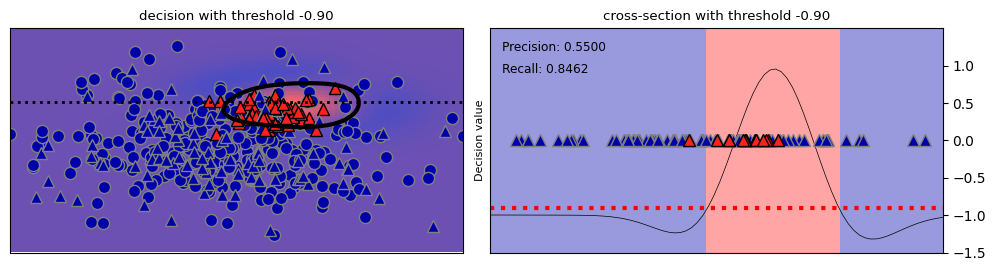

Threshold calibration¶

By default, we threshold at 0 for

decision_functionand 0.5 forpredict_probaDepending on the application, you may want to threshold differently

Lower threshold yields fewer FN (better recall), more FP (worse precision), and vice-versa

Source

from mglearn.datasets import make_blobs

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from mglearn.tools import plot_2d_separator, plot_2d_scores, cm, discrete_scatter

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interact_manual

Xs, ys = make_blobs(n_samples=(400, 50), centers=2, cluster_std=[7.0, 2],

random_state=22)

Xs_train, Xs_test, ys_train, ys_test = train_test_split(Xs, ys, stratify=ys, random_state=0)

svc1 = SVC(gamma=.04).fit(Xs_train, ys_train)

@interact

def plot_decision_threshold(threshold=(-1.2,1.3,0.1)):

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(8*fig_scale, 2.2*fig_scale), subplot_kw={'xticks': (), 'yticks': ()})

line = np.linspace(Xs_train.min(), Xs_train.max(), 100)

axes[0].set_title("decision with threshold {:.2f}".format(threshold))

discrete_scatter(Xs_train[:, 0], Xs_train[:, 1], ys_train, ax=axes[0], s=7*fig_scale)

discrete_scatter(Xs_test[:, 0], Xs_test[:, 1], ys_test, ax=axes[0], markers='^', s=7*fig_scale)

plot_2d_scores(svc1, Xs_train, function="decision_function", alpha=.7,

ax=axes[0], cm=mglearn.ReBl)

plot_2d_separator(svc1, Xs_train, linewidth=3, ax=axes[0], threshold=threshold)

axes[0].set_xlim(Xs_train[:, 0].min(), Xs_train[:, 0].max())

axes[0].plot(line, np.array([10 for i in range(len(line))]), 'k:', linewidth=2)

axes[1].set_title("cross-section with threshold {:.2f}".format(threshold))

axes[1].plot(line, svc1.decision_function(np.c_[line, 10 * np.ones(100)]), c='k')

dec = svc1.decision_function(np.c_[line, 10 * np.ones(100)])

contour = (dec > threshold).reshape(1, -1).repeat(10, axis=0)

axes[1].contourf(line, np.linspace(-1.5, 1.5, 10), contour, linewidth=2, alpha=0.4, cmap=cm)

discrete_scatter(Xs_test[:, 0], Xs_test[:, 1]*0, ys_test, ax=axes[1], markers='^', s=7*fig_scale)

axes[1].plot(line, np.array([threshold for i in range(len(line))]), 'r:', linewidth=3)

axes[1].tick_params(labelsize=8*fig_scale)

axes[0].set_xlim(Xs_train[:, 0].min(), Xs_train[:, 0].max())

axes[1].set_xlim(Xs_train[:, 0].min(), Xs_train[:, 0].max())

axes[1].set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

axes[1].set_xticks(())

axes[1].set_yticks(np.arange(-1.5, 1.5, 0.5))

axes[1].yaxis.tick_right()

axes[1].set_ylabel("Decision value")

y_pred = svc1.decision_function(Xs_test)

y_pred = y_pred > threshold

axes[1].text(Xs_train.min()+1,1.2,"Precision: {:.4f}".format(precision_score(ys_test,y_pred)), size=7*fig_scale)

axes[1].text(Xs_train.min()+1,0.9,"Recall: {:.4f}".format(recall_score(ys_test,y_pred)), size=7*fig_scale)

plt.tight_layout();

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_decision_threshold(0)

plot_decision_threshold(-0.9)<Figure size 1500x750 with 0 Axes>

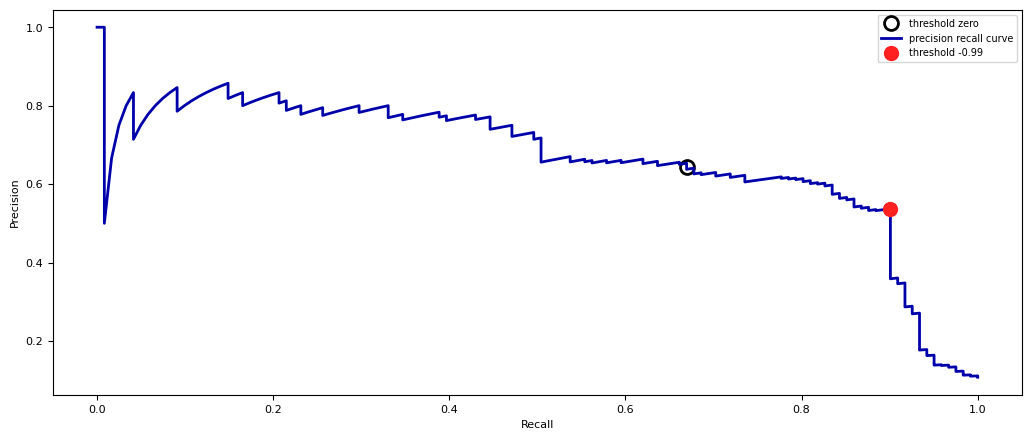

Precision-Recall curve¶

The best trade-off between precision and recall depends on your application

You can have arbitrary high recall, but you often want reasonable precision, too.

Plotting precision against recall for all possible thresholds yields a precision-recall curve

Change the treshold until you find a sweet spot in the precision-recall trade-off

Often jagged at high thresholds, when there are few positive examples left

Source

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

# create a similar dataset as before, but with more samples

# to get a smoother curve

Xp, yp = make_blobs(n_samples=(4000, 500), centers=2, cluster_std=[7.0, 2], random_state=22)

Xp_train, Xp_test, yp_train, yp_test = train_test_split(Xp, yp, random_state=0)

svc2 = SVC(gamma=.05).fit(Xp_train, yp_train)

rf2 = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100).fit(Xp_train, yp_train)

@interact

def plot_PR_curve(threshold=(-3.19,1.4,0.1), model=[svc2, rf2]):

if hasattr(model, "predict_proba"):

precision, recall, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(

yp_test, model.predict_proba(Xp_test)[:, 1])

else:

precision, recall, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(

yp_test, model.decision_function(Xp_test))

# find existing threshold closest to zero

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds))

plt.figure(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plt.plot(recall[close_zero], precision[close_zero], 'o', markersize=10,

label="threshold zero", fillstyle="none", c='k', mew=2)

plt.plot(recall, precision, lw=2, label="precision recall curve")

if hasattr(model, "predict_proba"):

yp_pred = model.predict_proba(Xp_test)[:, 1] > threshold

else:

yp_pred = model.decision_function(Xp_test) > threshold

plt.plot(recall_score(yp_test,yp_pred), precision_score(yp_test,yp_pred), 'o', markersize=10, label="threshold {:.2f}".format(threshold))

plt.ylabel("Precision")

plt.xlabel("Recall")

plt.legend(loc="best", prop={"size":7});

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_PR_curve(threshold=-0.99,model=svc2)

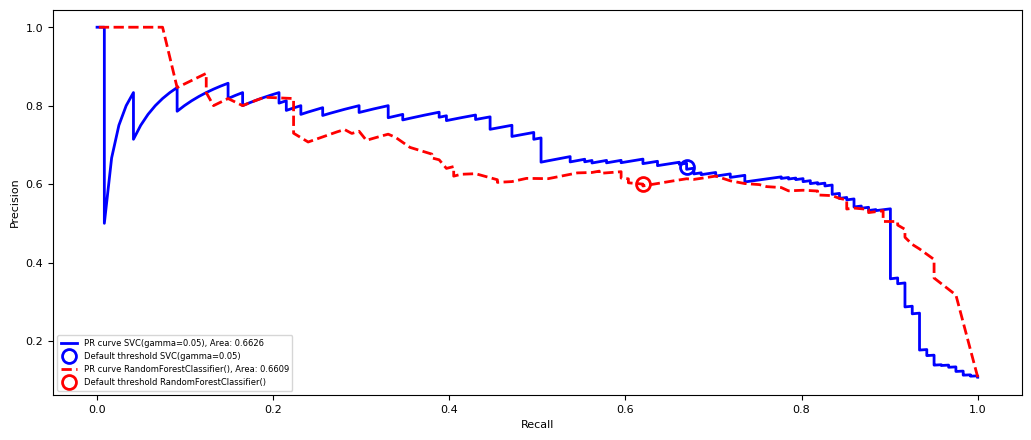

Model selection¶

Some models can achieve trade-offs that others can’t

Your application may require very high recall (or very high precision)

Choose the model that offers the best trade-off, given your application

The area under the PR curve (AUPRC) gives the best overall model

Source

from sklearn.metrics import auc

colors=['b','r','g','y']

def plot_PR_curves(models):

plt.figure(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

for i, model in enumerate(models):

if hasattr(model, "predict_proba"):

precision, recall, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(

yp_test, model.predict_proba(Xp_test)[:, 1])

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds-0.5))

else:

precision, recall, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(

yp_test, model.decision_function(Xp_test))

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds))

plt.plot(recall, precision, lw=2, c=colors[i], label="PR curve {}, Area: {:.4f}".format(model, auc(recall, precision)))

plt.plot(recall[close_zero], precision[close_zero], 'o', markersize=10,

fillstyle="none", c=colors[i], mew=2, label="Default threshold {}".format(model))

plt.ylabel("Precision")

plt.xlabel("Recall")

plt.legend(loc="lower left", prop={"size":6});

#svc2 = SVC(gamma=0.01).fit(X_train, y_train)

plot_PR_curves([svc2, rf2])

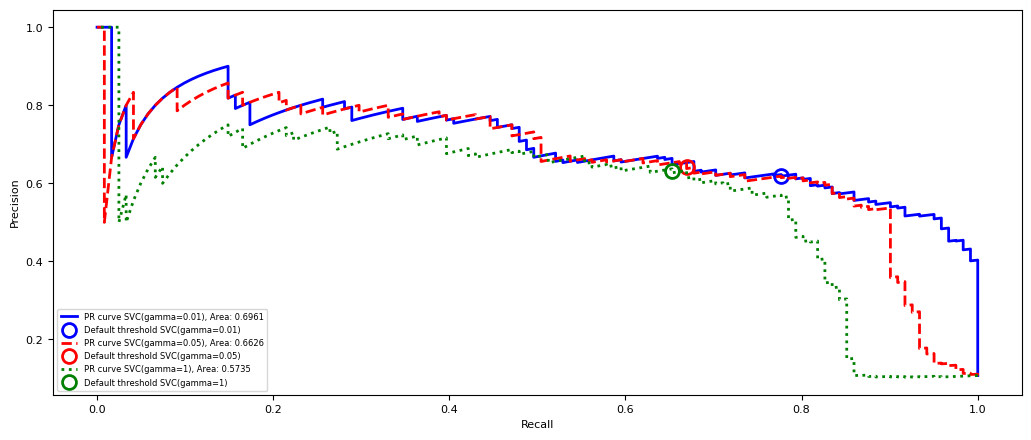

Hyperparameter effects¶

Of course, hyperparameters affect predictions and hence also the shape of the curve

Source

svc3 = SVC(gamma=0.01).fit(Xp_train, yp_train)

svc4 = SVC(gamma=1).fit(Xp_train, yp_train)

plot_PR_curves([svc3, svc2, svc4])

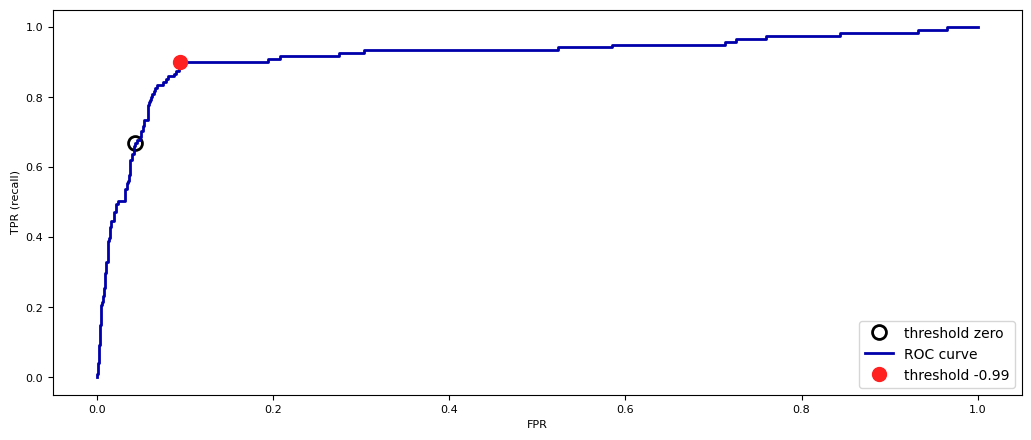

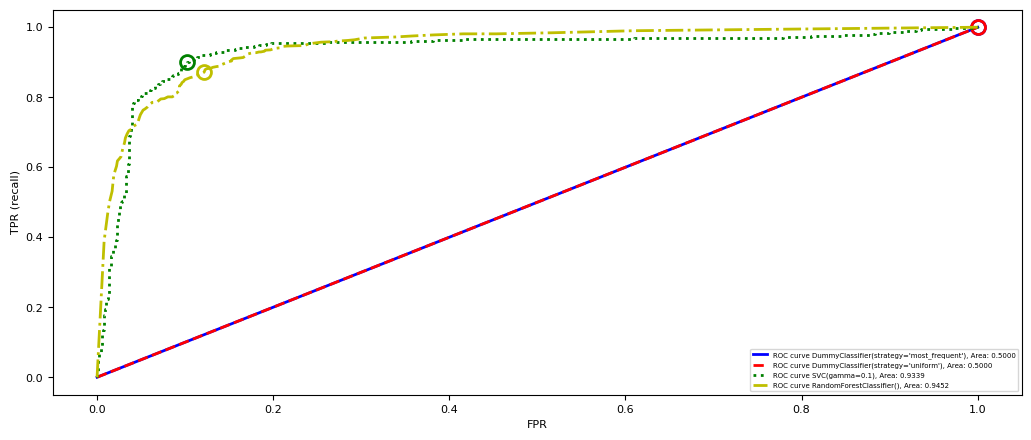

Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC)¶

Trade off true positive rate with false positive rate

Plotting TPR against FPR for all possible thresholds yields a Receiver Operating Characteristics curve

Change the treshold until you find a sweet spot in the TPR-FPR trade-off

Lower thresholds yield higher TPR (recall), higher FPR, and vice versa

Source

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve

@interact

def plot_ROC_curve(threshold=(-3.19,1.4,0.1), model=[svc2, rf2]):

if hasattr(model, "predict_proba"):

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(yp_test, model.predict_proba(Xp_test)[:, 1])

else:

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(yp_test, model.decision_function(Xp_test))

# find existing threshold closest to zero

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds))

plt.figure(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plt.plot(fpr[close_zero], tpr[close_zero], 'o', markersize=10, label="threshold zero", fillstyle="none", c='k', mew=2)

plt.plot(fpr, tpr, lw=2, label="ROC curve")

closest = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds-threshold))

plt.plot(fpr[closest], tpr[closest], 'o', markersize=10, label="threshold {:.2f}".format(threshold))

plt.ylabel("TPR (recall)")

plt.xlabel("FPR")

plt.legend(loc="best", prop={"size":10});

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_ROC_curve(threshold=-0.99,model=svc2)

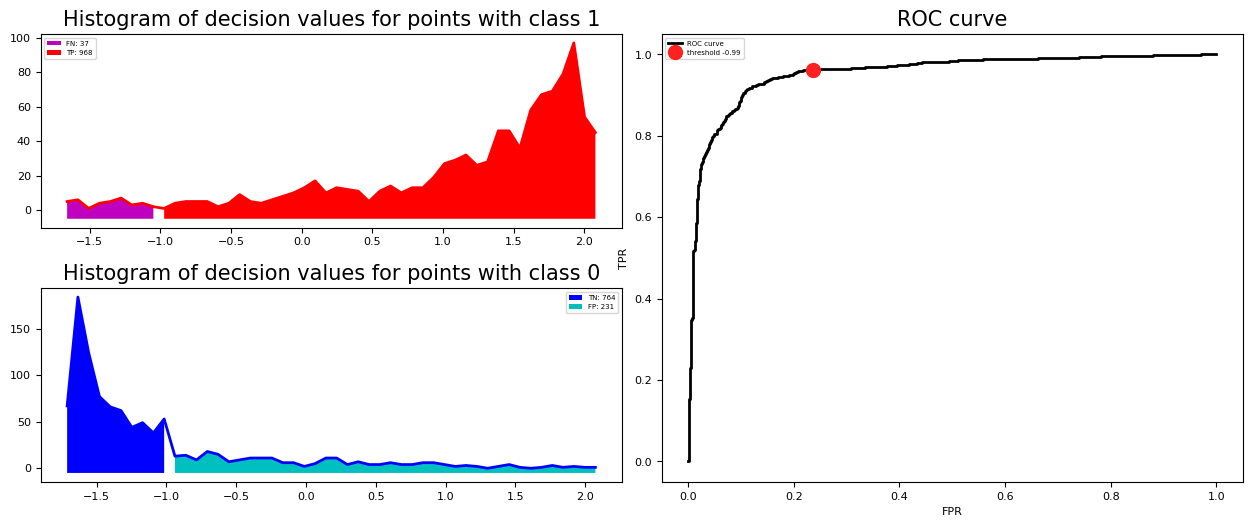

Visualization¶

Histograms show the amount of points with a certain decision value (for each class)

can be seen from the positive predictions (top histogram)

can be seen from the negative predictions (bottom histogram)

Source

# More data for a smoother curve

Xb, yb = make_blobs(n_samples=(4000, 4000), centers=2, cluster_std=[3, 3], random_state=7)

Xb_train, Xb_test, yb_train, yb_test = train_test_split(Xb, yb, random_state=0)

svc_roc = SVC(C=2).fit(Xb_train, yb_train)

probs_roc = svc_roc.decision_function(Xb_test)

@interact

def plot_roc_threshold(threshold=(-2,2,0.1)):

fig = plt.figure(constrained_layout=True, figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

axes = []

gs = fig.add_gridspec(2, 2)

axes.append(fig.add_subplot(gs[0, :-1]))

axes.append(fig.add_subplot(gs[1, :-1]))

axes.append(fig.add_subplot(gs[:, 1]))

n=50 # number of histogram bins

color=['b','r']

color_fill=['b','c','m','r']

labels=['TN','FP','FN','TP']

# Histograms

for label in range(2):

ps = probs_roc[yb_test == label] # get prediction for given label

p, x = np.histogram(ps, bins=n) # bin it into n bins

x = x[:-1] + (x[1] - x[0])/2 # convert bin edges to center

axes[1-label].plot(x, p, c=color[label], lw=2)

axes[1-label].fill_between(x[x<threshold], p[x<threshold], -5, facecolor=color_fill[2*label], label='{}: {}'.format(labels[2*label],np.sum(p[x<threshold])))

axes[1-label].fill_between(x[x>=threshold], p[x>threshold], -5, facecolor=color_fill[2*label+1], label='{}: {}'.format(labels[2*label+1],np.sum(p[x>=threshold])))

axes[1-label].set_title('Histogram of decision values for points with class {}'.format(label), fontsize=12*fig_scale)

axes[1-label].legend(prop={"size":5})

#ROC curve

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(yb_test, svc_roc.decision_function(Xb_test))

axes[2].plot(fpr, tpr, lw=2, label="ROC curve", c='k')

closest = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds-threshold))

axes[2].plot(fpr[closest], tpr[closest], 'o', markersize=10, label="threshold {:.2f}".format(threshold))

axes[2].set_title('ROC curve', fontsize=12*fig_scale)

axes[2].set_xlabel("FPR")

axes[2].set_ylabel("TPR")

axes[2].legend(prop={"size":5})

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_roc_threshold(threshold=-0.99)

Model selection¶

Again, some models can achieve trade-offs that others can’t

Your application may require minizing FPR (low FP), or maximizing TPR (low FN)

The area under the ROC curve (AUROC or AUC) gives the best overall model

Frequently used for evaluating models on imbalanced data

Random guessing (TPR=FPR) or predicting majority class (TPR=FPR=1): 0.5 AUC

Source

from sklearn.metrics import auc

from sklearn.dummy import DummyClassifier

def plot_ROC_curves(models):

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

for i, model in enumerate(models):

if hasattr(model, "predict_proba"):

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(

yb_test, model.predict_proba(Xb_test)[:, 1])

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds-0.5))

else:

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(

yb_test, model.decision_function(Xb_test))

close_zero = np.argmin(np.abs(thresholds))

plt.plot(fpr, tpr, lw=2, c=colors[i], label="ROC curve {}, Area: {:.4f}".format(model, auc(fpr, tpr)))

plt.plot(fpr[close_zero], tpr[close_zero], 'o', markersize=10,

fillstyle="none", c=colors[i], mew=2) #label="Default threshold {}".format(model)

plt.ylabel("TPR (recall)")

plt.xlabel("FPR")

plt.legend(loc="lower right",prop={"size":5});

svc = SVC(gamma=.1).fit(Xb_train, yb_train)

rf = RandomForestClassifier(n_estimators=100).fit(Xb_train, yb_train)

dc = DummyClassifier(strategy='most_frequent').fit(Xb_train, yb_train)

dc2 = DummyClassifier(strategy='uniform').fit(Xb_train, yb_train)

plot_ROC_curves([dc, dc2, svc, rf])

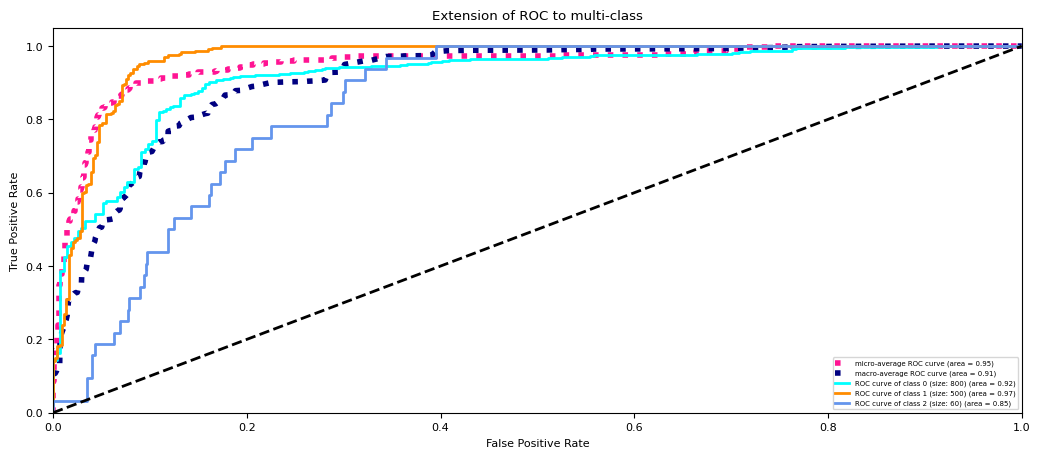

Multi-class AUROC (or AUPRC)¶

We again need to choose between micro- or macro averaging TPR and FPR.

Micro-average if every sample is equally important (irrespective of class)

Macro-average if every class is equally important, especially for imbalanced data

Source

from itertools import cycle

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve, auc

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import label_binarize

from sklearn.multiclass import OneVsRestClassifier

from numpy import interp

from sklearn.metrics import roc_auc_score

# 3 class imbalanced data

Xi, yi = make_blobs(n_samples=(800, 500, 60), centers=3, cluster_std=[7.0, 2, 3.0], random_state=22)

sizes = [800, 500, 60]

# Binarize the output

yi = label_binarize(yi, classes=[0, 1, 2])

n_classes = yi.shape[1]

Xi_train, Xi_test, yi_train, yi_test = train_test_split(Xi, yi, test_size=.5, random_state=0)

# Learn to predict each class against the other

classifier = OneVsRestClassifier(SVC(probability=True))

y_score = classifier.fit(Xi_train, yi_train).decision_function(Xi_test)

# Compute ROC curve and ROC area for each class

fpr = dict()

tpr = dict()

roc_auc = dict()

for i in range(n_classes):

fpr[i], tpr[i], _ = roc_curve(yi_test[:, i], y_score[:, i])

roc_auc[i] = auc(fpr[i], tpr[i])

# Compute micro-average ROC curve and ROC area

fpr["micro"], tpr["micro"], _ = roc_curve(yi_test.ravel(), y_score.ravel())

roc_auc["micro"] = auc(fpr["micro"], tpr["micro"])

# First aggregate all false positive rates

all_fpr = np.unique(np.concatenate([fpr[i] for i in range(n_classes)]))

# Then interpolate all ROC curves at this points

mean_tpr = np.zeros_like(all_fpr)

for i in range(n_classes):

mean_tpr += interp(all_fpr, fpr[i], tpr[i])

# Finally average it and compute AUC

mean_tpr /= n_classes

fpr["macro"] = all_fpr

tpr["macro"] = mean_tpr

roc_auc["macro"] = auc(fpr["macro"], tpr["macro"])

# Plot all ROC curves

plt.figure(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plt.plot(fpr["micro"], tpr["micro"],

label='micro-average ROC curve (area = {0:0.2f})'

''.format(roc_auc["micro"]),

color='deeppink', linestyle=':', linewidth=4)

plt.plot(fpr["macro"], tpr["macro"],

label='macro-average ROC curve (area = {0:0.2f})'

''.format(roc_auc["macro"]),

color='navy', linestyle=':', linewidth=4)

colors = cycle(['aqua', 'darkorange', 'cornflowerblue'])

for i, color in zip(range(n_classes), colors):

plt.plot(fpr[i], tpr[i], color=color, lw=2, linestyle='-',

label='ROC curve of class {} (size: {}) (area = {:0.2f})'

''.format(i, sizes[i], roc_auc[i]))

plt.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], 'k--', lw=2)

plt.xlim([0.0, 1.0])

plt.ylim([0.0, 1.05])

plt.xlabel('False Positive Rate')

plt.ylabel('True Positive Rate')

plt.title('Extension of ROC to multi-class')

plt.legend(loc="lower right", prop={"size":5})

plt.show()

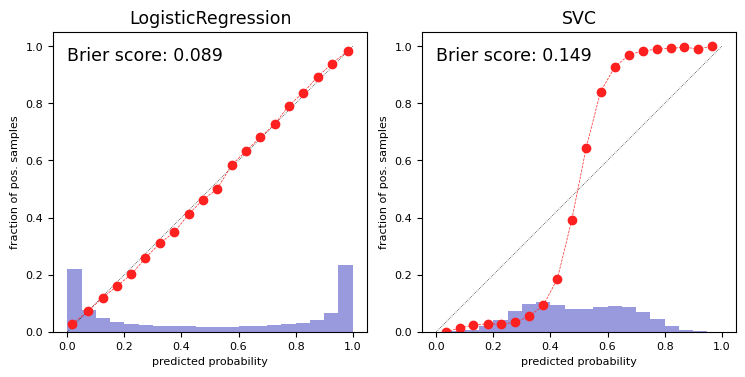

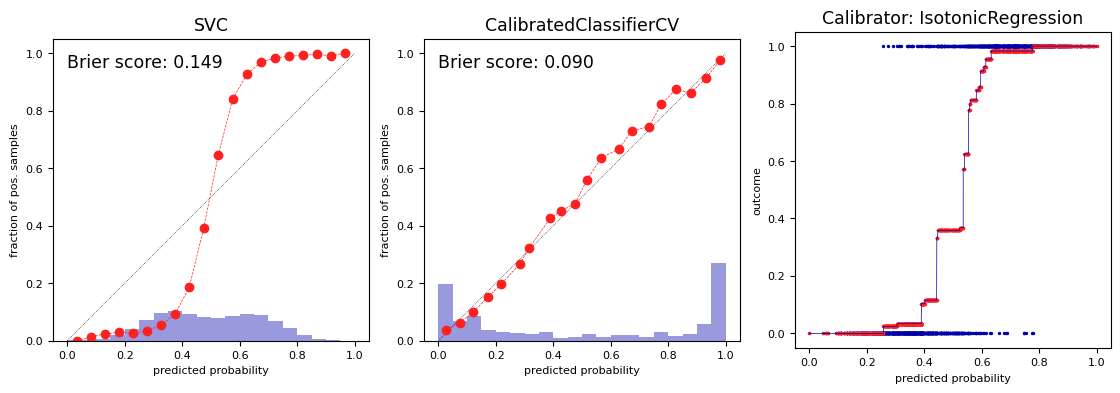

Model calibration¶

For some models, the predicted uncertainty does not reflect the actual uncertainty

If a model is 90% sure that samples are positive, is it also 90% accurate on these?

A model is called calibrated if the reported uncertainty actually matches how correct it is

Overfitted models also tend to be over-confident

LogisticRegression models are well calibrated since they learn probabilities

SVMs are not well calibrated. Biased towards points close to the decision boundary.

Source

from sklearn.svm import SVC

from sklearn.datasets import make_classification

from sklearn.calibration import calibration_curve

from sklearn.metrics import brier_score_loss, accuracy_score

def load_data():

X, y = make_classification(n_samples=100000, n_features=20, random_state=0)

train_samples = 2000 # Samples used for training the models

X_train = X[:train_samples]

X_test = X[train_samples:]

y_train = y[:train_samples]

y_test = y[train_samples:]

return X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test

Xc_train, Xc_test, yc_train, yc_test = load_data()

def plot_calibration_curve(y_true, y_prob, n_bins=5, ax=None, hist=True, normalize=False):

prob_true, prob_pred = calibration_curve(y_true, y_prob, n_bins=n_bins)

if ax is None:

ax = plt.gca()

if hist:

ax.hist(y_prob, weights=np.ones_like(y_prob) / len(y_prob), alpha=.4,

bins=np.maximum(10, n_bins))

ax.plot([0, 1], [0, 1], ':', c='k')

curve = ax.plot(prob_pred, prob_true, marker="o")

ax.set_xlabel("predicted probability")

ax.set_ylabel("fraction of pos. samples")

ax.set(aspect='equal')

return curve

# Plot calibration curves for `models`, optionally show a calibrator run on a calibratee

def plot_calibration_comparison(models, calibrator=None, calibratee=None):

def get_probabilities(clf, X):

if hasattr(clf, "predict_proba"): # Use probabilities if classifier has predict_proba

prob_pos = clf.predict_proba(X)[:, 1]

else: # Otherwise, use decision function and scale

prob_pos = clf.decision_function(X)

prob_pos = (prob_pos - prob_pos.min()) / (prob_pos.max() - prob_pos.min())

return prob_pos

nr_plots = len(models)

if calibrator:

nr_plots += 1

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, nr_plots, figsize=(3*nr_plots*fig_scale, 4*nr_plots*fig_scale))

for ax, clf in zip(axes[:len(models)], models):

clf.fit(Xc_train, yc_train)

prob_pos = get_probabilities(clf,Xc_test)

bs = brier_score_loss(yc_test,prob_pos)

plot_calibration_curve(yc_test, prob_pos, n_bins=20, ax=ax)

ax.set_title(clf.__class__.__name__, fontsize=10*fig_scale)

ax.text(0,0.95,"Brier score: {:.3f}".format(bs), size=10*fig_scale)

if calibrator:

calibratee.fit(Xc_train, yc_train)

# We're visualizing the trained calibrator, hence let it predict the training data

prob_pos = get_probabilities(calibratee, Xc_train) # get uncalibrated predictions

y_sort = [x for _,x in sorted(zip(prob_pos,yc_train))] # sort for nicer plots

prob_pos.sort()

cal_prob = calibrator.fit(prob_pos, y_sort).predict(prob_pos) # fit calibrator

axes[-1].scatter(prob_pos,y_sort, s=2)

axes[-1].scatter(prob_pos,cal_prob, s=2)

axes[-1].plot(prob_pos,cal_prob)

axes[-1].set_title("Calibrator: {}".format(calibrator.__class__.__name__), fontsize=10*fig_scale)

axes[-1].set_xlabel("predicted probability")

axes[-1].set_ylabel("outcome")

axes[-1].set(aspect='equal')

plt.tight_layout()

plot_calibration_comparison([LogisticRegression(), SVC()])

Brier score¶

You may want to select models based on how accurate the class confidences are.

The Brier score loss: squared loss between predicted probability and actual outcome

Lower is better

Source

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

XC_train, XC_test, yC_train, yC_test = train_test_split(cancer.data, cancer.target, test_size=.5, random_state=0)

# LogReg

logreg = LogisticRegression().fit(XC_train, yC_train)

probs = logreg.predict_proba(XC_test)[:,1]

print("Logistic Regression Brier score loss: {:.4f}".format(brier_score_loss(yC_test,probs)))

# SVM: scale decision functions

svc = SVC().fit(XC_train, yC_train)

prob_pos = svc.decision_function(XC_test)

prob_pos = (prob_pos - prob_pos.min()) / (prob_pos.max() - prob_pos.min())

print("SVM Brier score loss: {:.4f}".format(brier_score_loss(yC_test,prob_pos)))Logistic Regression Brier score loss: 0.0322

SVM Brier score loss: 0.0795

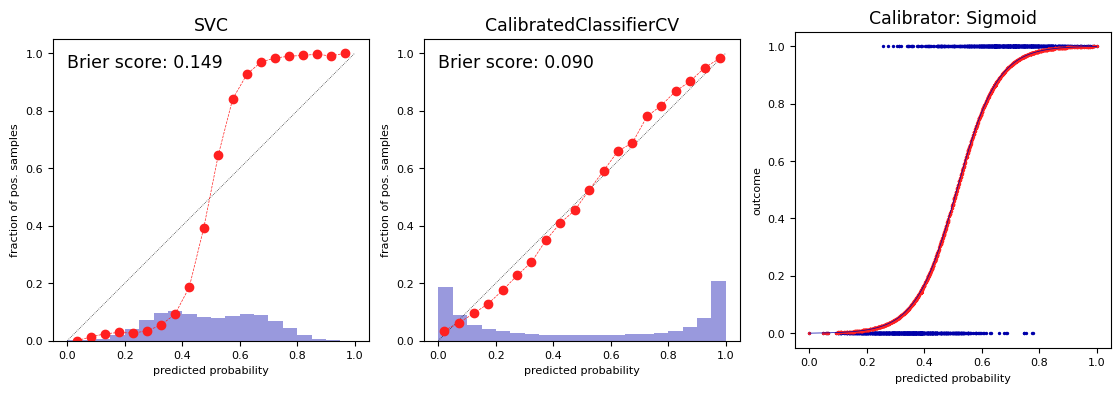

Model calibration techniques¶

We can post-process trained models to make them more calibrated.

Fit a regression model (a calibrator) to map the model’s outcomes to a calibrated probability in [0,1]

returns the decision values or probability estimates

is fitted on the training data to map these to the correct outcome

Often an internal cross-validation with few folds is used

Multi-class models require one calibrator per class

Source

from sklearn.calibration import CalibratedClassifierCV

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

# Wrapped LogisticRegression to get sigmoid predictions

class Sigmoid():

model = LogisticRegression()

def fit(self, X, y):

self.model.fit(X.reshape(-1, 1),y)

return self

def predict(self, X):

return self.model.predict_proba(X.reshape(-1, 1))[:, 1]

svm = SVC()

svm_platt = CalibratedClassifierCV(svm, cv=2, method='sigmoid')

plot_calibration_comparison([svm, svm_platt],Sigmoid(),svm)

Isotonic regression¶

Maps input to an output so that increases monotonically with and minimizes loss

Predictions are made by interpolating the predicted

Fit to minimize the loss between the uncalibrated predictions and the actual labels

Corrects any monotonic distortion, but tends to overfit on small samples

Source

from sklearn.isotonic import IsotonicRegression

model = SVC()

iso = CalibratedClassifierCV(model, cv=2, method='isotonic')

plot_calibration_comparison([model, iso],IsotonicRegression(),model)

Cost-sensitive classification (dealing with imbalance)¶

In the real world, different kinds of misclassification can have different costs

Misclassifying certain classes can be more costly than others

Misclassifying certain samples can be more costly than others

Cost-sensitive resampling: resample (or reweight) the data to represent real-world expectations

oversample minority classes (or undersample majority) to ‘correct’ imbalance

increase weight of misclassified samples (e.g. in boosting)

decrease weight of misclassified (noisy) samples (e.g. in model compression)

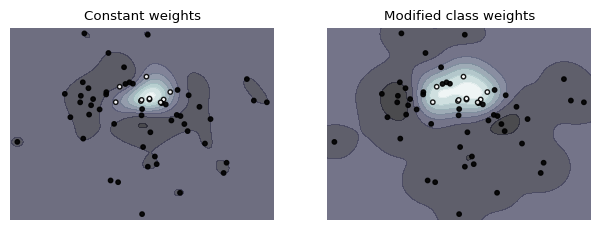

Class weighting¶

If some classes are more important than others, we can give them more weight

E.g. for imbalanced data, we can give more weight to minority classes

Most classification models can include it in their loss function and optimize for it

E.g. Logistic regression: add a class weight in the log loss function

Source

def plot_decision_function(classifier, X, y, sample_weight, axis, title):

# plot the decision function

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.linspace(np.min(X[:,0])-1, np.max(X[:,0])+1, 500), np.linspace(np.min(X[:,1])-1, np.max(X[:,1])+1, 500))

Z = classifier.decision_function(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

# plot the line, the points, and the nearest vectors to the plane

axis.contourf(xx, yy, Z, alpha=0.75, cmap=plt.cm.bone)

axis.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=y, s=10 * sample_weight, alpha=0.9,

cmap=plt.cm.bone, edgecolors='black')

axis.axis('off')

axis.set_title(title)

def plot_class_weights():

X, y = make_blobs(n_samples=(50, 10), centers=2, cluster_std=[7.0, 2], random_state=4)

# fit the models

clf_weights = SVC(gamma=0.1, C=0.1, class_weight={1: 10}).fit(X, y)

clf_no_weights = SVC(gamma=0.1, C=0.1).fit(X, y)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(6*fig_scale, 2*fig_scale))

plot_decision_function(clf_no_weights, X, y, 1, axes[0],

"Constant weights")

plot_decision_function(clf_weights, X, y, 1, axes[1],

"Modified class weights")

plot_class_weights()

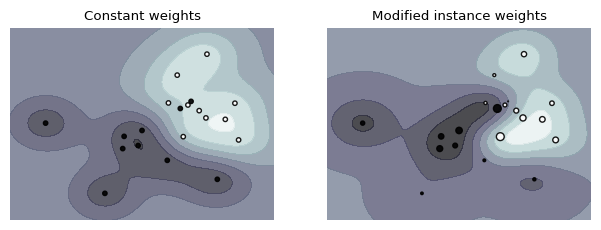

Instance weighting¶

If some training instances are important to get right, we can give them more weight

E.g. when some examples are from groups underrepresented in the data

These are passed during training (fit), and included in the loss function

E.g. Logistic regression: add a instance weight in the log loss function

Source

# Example from https://scikit-learn.org/stable/auto_examples/svm/plot_weighted_samples.html

def plot_instance_weights():

np.random.seed(0)

X = np.r_[np.random.randn(10, 2) + [1, 1], np.random.randn(10, 2)]

y = [1] * 10 + [-1] * 10

sample_weight_last_ten = abs(np.random.randn(len(X)))

sample_weight_constant = np.ones(len(X))

# and bigger weights to some outliers

sample_weight_last_ten[15:] *= 5

sample_weight_last_ten[9] *= 15

# for reference, first fit without sample weights

# fit the model

clf_weights = SVC(gamma=1)

clf_weights.fit(X, y, sample_weight=sample_weight_last_ten)

clf_no_weights = SVC(gamma=1)

clf_no_weights.fit(X, y)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(6*fig_scale, 2*fig_scale))

plot_decision_function(clf_no_weights, X, y, sample_weight_constant, axes[0],

"Constant weights")

plot_decision_function(clf_weights, X, y, sample_weight_last_ten, axes[1],

"Modified instance weights")

plot_instance_weights()

Cost-sensitive algorithms¶

Cost-sensitive algorithms

If misclassification cost of some classes is higher, we can give them higher weights

Some support cost matrix : costs for every possible type of error

Cost-sensitive ensembles: convert cost-insensitive classifiers into cost-sensitive ones

MetaCost: Build a model (ensemble) to learn the class probabilities

Relabel training data to minimize expected cost:

Accuracy may decrease but cost decreases as well.

AdaCost: Boosting with reweighting instances to reduce costs

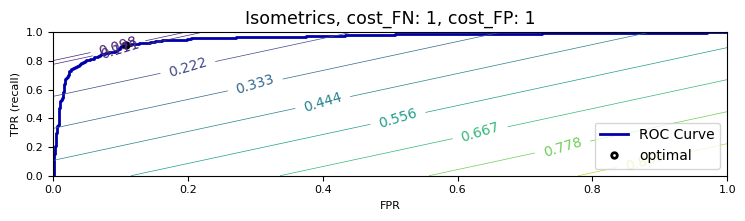

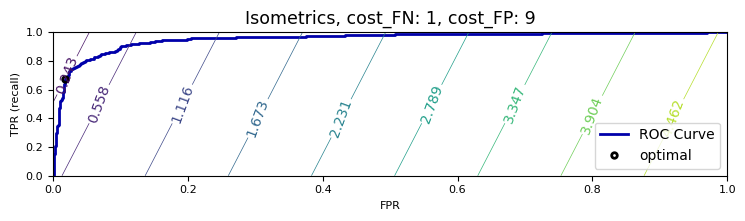

Tuning the decision threshold¶

If every FP or FN has a certain cost, we can compute the total cost for a given model:

This yields different isometrics (lines of equal cost) in ROC space

Optimal threshold is the point on the ROC curve where cost is minimal (line search)

Source

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interact_manual

# Cost function

def cost(fpr, tpr, cost_FN, cost_FP, ratio_P):

return fpr * cost_FP * ratio_P + (1 - tpr) * (1-ratio_P) * cost_FN;

@interact

def plot_isometrics(cost_FN=(1,10.0,1.0), cost_FP=(1,10.0,1.0)):

from sklearn.metrics import roc_curve

fpr, tpr, thresholds = roc_curve(yb_test, svc_roc.decision_function(Xb_test))

# get minimum

ratio_P = len(yb_test[yb_test==1]) / len(yb_test)

costs = [cost(fpr[x],tpr[x],cost_FN,cost_FP, ratio_P) for x in range(len(thresholds))]

min_cost = np.min(costs)

min_thres = np.argmin(costs)

# plot contours

x = np.arange(0.0, 1.1, 0.1)

y = np.arange(0.0, 1.1, 0.1)

XX, YY = np.meshgrid(x, y)

costs = [cost(f, t, cost_FN, cost_FP, ratio_P) for f, t in zip(XX,YY)]

if interactive:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(9*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

else:

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(6*fig_scale, 1.8*fig_scale))

plt.plot(fpr, tpr, label="ROC Curve", lw=2)

levels = np.linspace(np.array(costs).min(), np.array(costs).max(), 10)

levels = np.sort(np.append(levels, min_cost))

CS = plt.contour(XX, YY, costs, levels)

plt.clabel(CS, inline=1, fontsize=10)

plt.xlabel("FPR")

plt.ylabel("TPR (recall)")

# find threshold closest to zero:

plt.plot(fpr[min_thres], tpr[min_thres], 'o', markersize=4,

label="optimal", fillstyle="none", c='k', mew=2)

plt.legend(loc=4, prop={"size":10});

plt.title("Isometrics, cost_FN: {}, cost_FP: {}".format(cost_FN, cost_FP), fontsize=10*fig_scale)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_isometrics(1,1)

plot_isometrics(1,9)

Regression metrics¶

Most commonly used are

mean squared error:

root mean squared error (RMSE) often used as well

mean absolute error:

Less sensitive to outliers and large errors

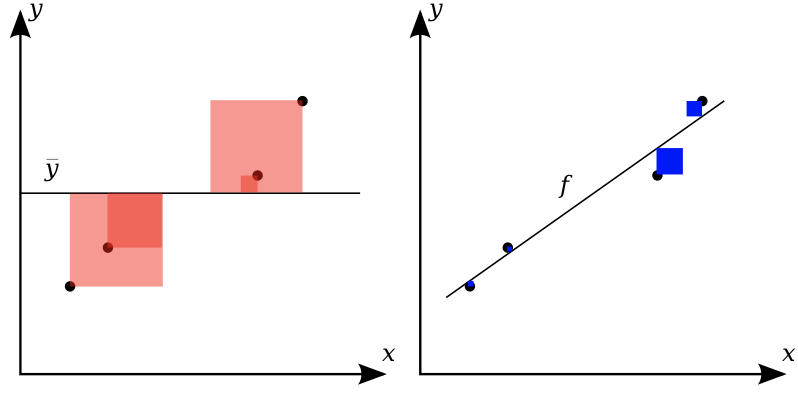

R squared¶

Ratio of variation explained by the model / total variation

Between 0 and 1, but negative if the model is worse than just predicting the mean

Easier to interpret (higher is better).

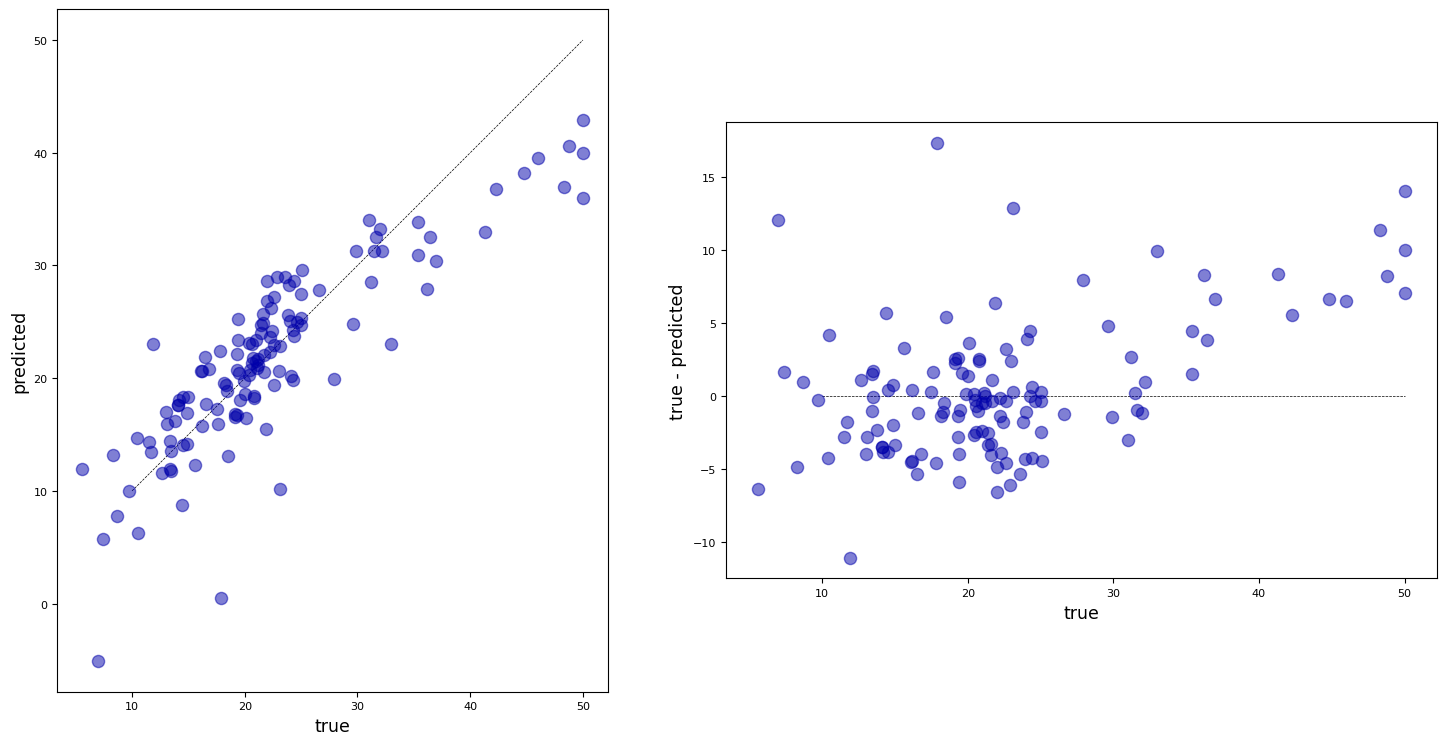

Visualizing regression errors¶

Prediction plot (left): predicted vs actual target values

Residual plot (right): residuals vs actual target values

Over- and underpredictions can be given different costs

Source

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

boston = fetch_openml(name="boston", as_frame=True)

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(boston.data, boston.target)

ridge_pipe = make_pipeline(StandardScaler(),Ridge())

pred = ridge_pipe.fit(X_train, y_train).predict(X_test)

plt.subplot(1, 2, 1)

plt.gca().set_aspect("equal")

plt.plot([10, 50], [10, 50], '--', c='k')

plt.plot(y_test, pred, 'o', alpha=.5, markersize=7*fig_scale)

plt.ylabel("predicted", fontsize=10*fig_scale)

plt.xlabel("true", fontsize=10*fig_scale);

plt.subplot(1, 2, 2)

plt.gca().set_aspect("equal")

plt.plot([10, 50], [0,0], '--', c='k')

plt.plot(y_test, y_test - pred, 'o', alpha=.5, markersize=7*fig_scale)

plt.xlabel("true", fontsize=10*fig_scale)

plt.ylabel("true - predicted", fontsize=10*fig_scale)

plt.tight_layout();

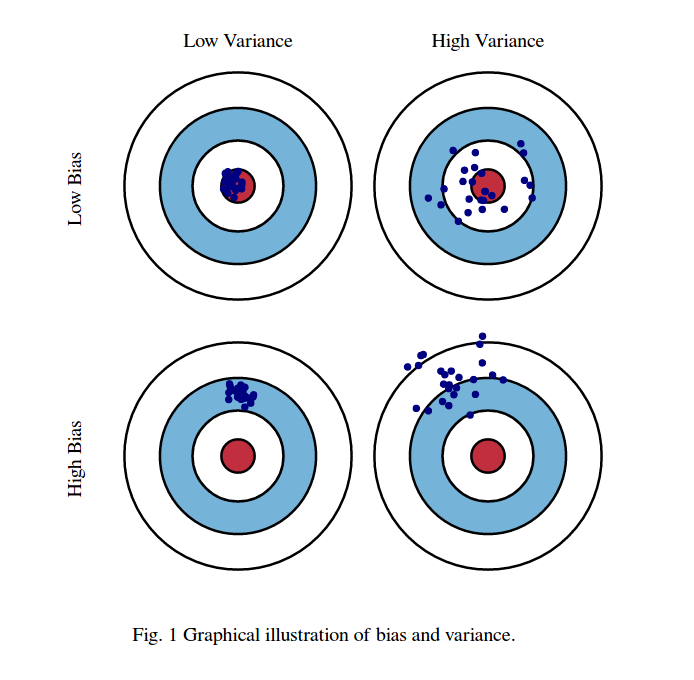

Bias-Variance decomposition¶

Evaluate the same algorithm multiple times on different random samples of the data

Two types of errors can be observed:

Bias error: systematic error, independent of the training sample

These points are predicted (equally) wrong every time

Variance error: error due to variability of the model w.r.t. the training sample

These points are sometimes predicted accurately, sometimes inaccurately

Computing bias and variance error¶

Take 100 or more bootstraps (or shuffle-splits)

Regression: for each data point x:

Classification: for each data point x:

= misclassification ratio

is ratio of class predictions

Total bias: : the percentage of times occurs in the test sets

Total variance:

Source

from sklearn.model_selection import ShuffleSplit, train_test_split, GridSearchCV

# Bias-Variance Computation

def compute_bias_variance(clf, X, y):

# Bootstraps

n_repeat = 40 # 40 is on the low side to get a good estimate. 100 is better.

shuffle_split = ShuffleSplit(test_size=0.33, n_splits=n_repeat, random_state=0)

# Store sample predictions

y_all_pred = [[] for _ in range(len(y))]

# Train classifier on each bootstrap and score predictions

for i, (train_index, test_index) in enumerate(shuffle_split.split(X)):

# Train and predict

clf.fit(X[train_index], y[train_index])

y_pred = clf.predict(X[test_index])

# Store predictions

for j,index in enumerate(test_index):

y_all_pred[index].append(y_pred[j])

# Compute bias, variance, error

bias_sq = sum([ (1 - x.count(y[i])/len(x))**2 * len(x)/n_repeat

for i,x in enumerate(y_all_pred)])

var = sum([((1 - ((x.count(0)/len(x))**2 + (x.count(1)/len(x))**2))/2) * len(x)/n_repeat

for i,x in enumerate(y_all_pred)])

error = sum([ (1 - x.count(y[i])/len(x)) * len(x)/n_repeat

for i,x in enumerate(y_all_pred)])

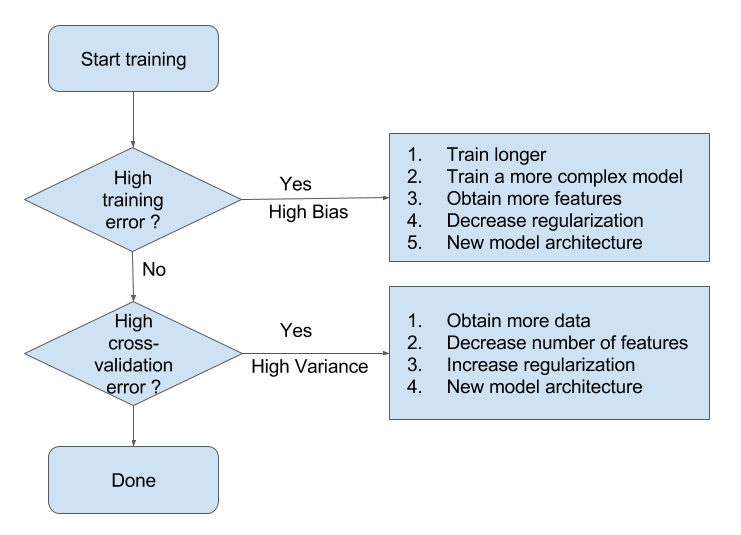

return np.sqrt(bias_sq), var, errorBias and variance, underfitting and overfitting¶

High variance means that you are likely overfitting

Use more regularization or use a simpler model

High bias means that you are likely underfitting

Do less regularization or use a more flexible/complex model

Ensembling techniques (see later) reduce bias or variance directly

Bagging (e.g. RandomForests) reduces variance, Boosting reduces bias

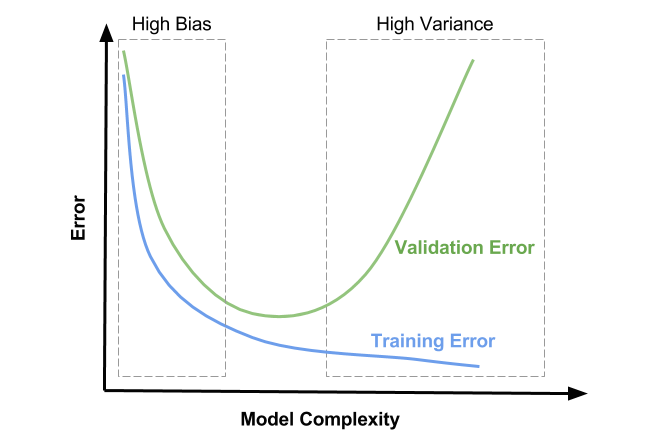

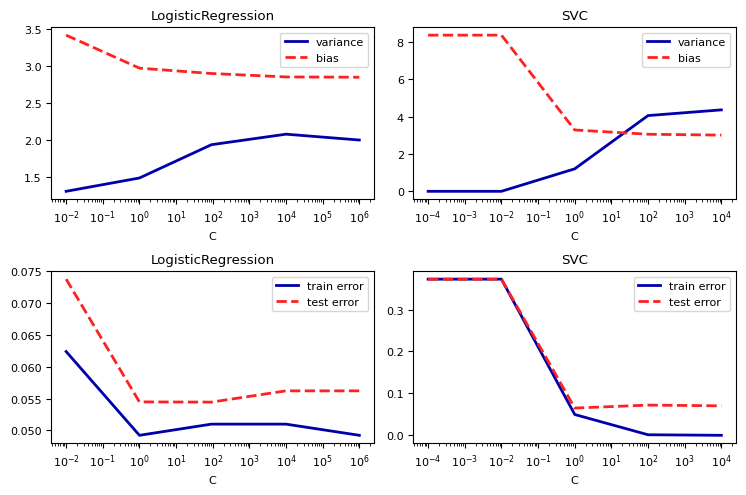

Understanding under- and overfitting¶

Regularization reduces variance error (increases stability of predictions)

But too much increases bias error (inability to learn ‘harder’ points)

High regularization (left side): Underfitting, high bias error, low variance error

High training error and high test error

Low regularization (right side): Overfitting, low bias error, high variance error

Low training error and higher test error

Source

from sklearn.datasets import load_breast_cancer

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestClassifier, AdaBoostClassifier

cancer = load_breast_cancer()

def plot_bias_variance(clf, param, X, y, ax):

bias_scores = []

var_scores = []

err_scores = []

name, vals = next(iter(param.items()))

for i in vals:

b,v,e = compute_bias_variance(clf.set_params(**{name:i}),X,y)

bias_scores.append(b)

var_scores.append(v)

err_scores.append(e)

ax.set_title(clf.__class__.__name__)

ax.plot(vals, var_scores,label ="variance", lw=2 )

ax.plot(vals, bias_scores,label ="bias", lw=2 )

ax.set_xscale('log')

ax.set_xlabel(name)

ax.legend(loc="best")

def plot_train_test(clf, param, X, y, ax):

gs = GridSearchCV(clf, param, cv=5, return_train_score=True).fit(X,y)

name, vals = next(iter(param.items()))

ax.set_title(clf.__class__.__name__)

ax.plot(vals, (1-gs.cv_results_['mean_train_score']),label ="train error", lw=2 )

ax.plot(vals, (1-gs.cv_results_['mean_test_score']),label ="test error", lw=2 )

ax.set_xscale('log')

ax.set_xlabel(name)

ax.legend(loc="best")

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(6*fig_scale, 4*fig_scale))

X, y = cancer.data, cancer.target

svm = SVC(gamma=2e-4, random_state=0)

param = {'C': [1e-4, 1e-2, 1, 1e2, 1e4]}

plot_bias_variance(svm, param, X, y, axes[0,1])

plot_train_test(svm, param, X, y, axes[1,1])

lr = LogisticRegression(random_state=0)

param = {'C': [1e-2, 1, 92, 1e4, 1e6]}

plot_bias_variance(lr, param, X, y, axes[0,0])

plot_train_test(lr, param, X, y, axes[1,0])

plt.tight_layout()

Summary Flowchart (by Andrew Ng)

Hyperparameter tuning¶

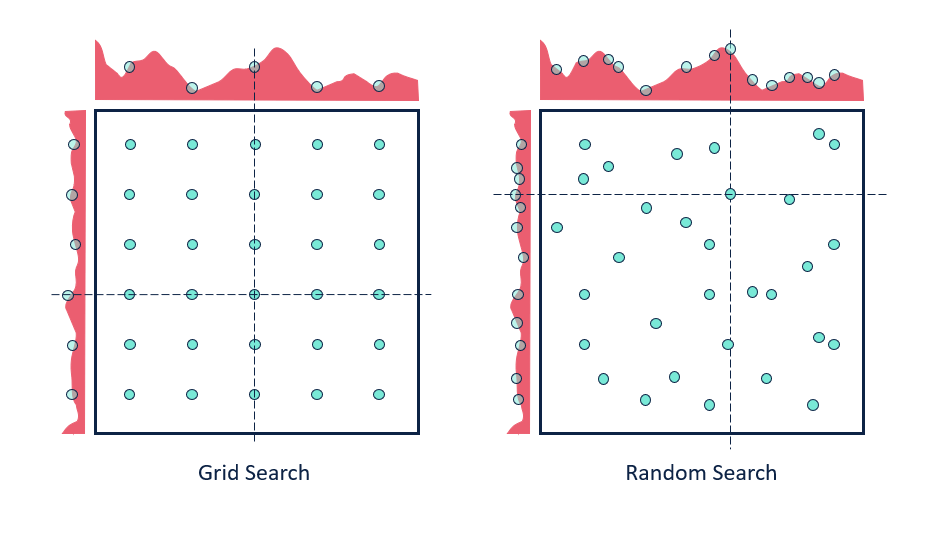

There exists a huge range of techniques to tune hyperparameters. The simplest:

Grid search: Choose a range of values for every hyperparameter, try every combination

Doesn’t scale to many hyperparameters (combinatorial explosion)

Random search: Choose random values for all hyperparameters, iterate times

Better, especially when some hyperparameters are less important

Many more advanced techniques exist, see lecture on Automated Machine Learning

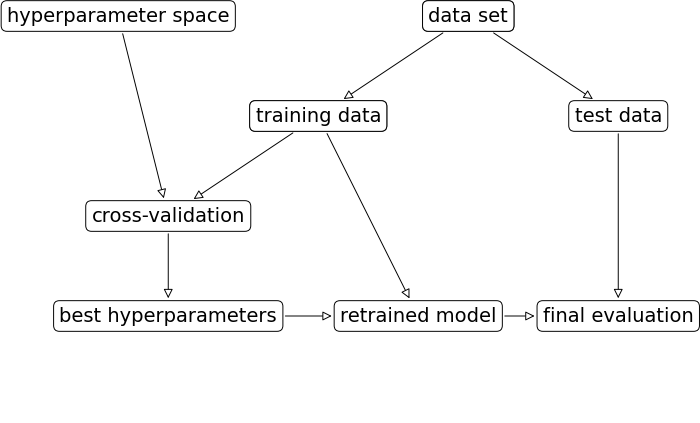

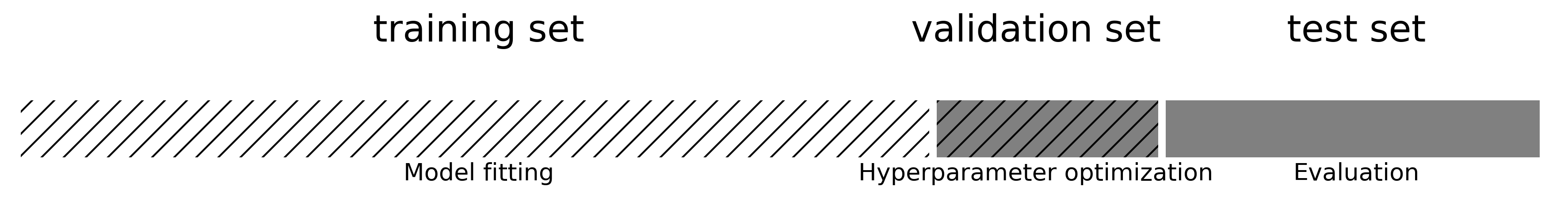

First, split the data in training and test sets (outer split)

Split up the training data again (inner cross-validation)

Generate hyperparameter configurations (e.g. random/grid search)

Evaluate all configurations on all inner splits, select the best one (on average)

Retrain best configurations on full training set, evaluate on held-out test data

Source

if interactive:

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi'] = 75

else:

plt.rcParams['figure.dpi'] = 70

mglearn.plots.plot_grid_search_overview()

plt.rcParams.update(print_config)

Source

from scipy.stats.distributions import exponNested cross-validation¶

Simplest approach: single outer split and single inner split (shown below)

Risk of over-tuning hyperparameters on specific train-test split

Only recommended for very large datasets

Nested cross-validation:

Outer loop: split full dataset in training and test splits

Inner loop: split training data into train and validation sets

This yields scores for possibly different hyperparameter settings

Average score is the expected performance of the tuned model

To use the model in practice, retune on the entire dataset

hps = {'C': expon(scale=100), 'gamma': expon(scale=.1)}

scores = cross_val_score(RandomizedSearchCV(SVC(), hps, cv=3), X, y, cv=5)Source

mglearn.plots.plot_threefold_split()

Summary¶

Split the data into training and test sets according to the application

Holdout only for large datasets, cross-validation for smaller ones

For classification, always use stratification

Grouped or ordered data requires special splitting

Choose a metric that fits your application

E.g. precision to avoid false positives, recall to avoid false negatives

Calibrate the decision threshold to fit your application

ROC curves or Precision-Recall curves can help to find a good tradeoff

If possible, include the actual or relative costs of misclassifications

Class weighting, instance weighting, ROC isometrics can help

Be careful with imbalanced or unrepresentative datasets

When using the predicted probabilities in applications, calibrate the models

Always tune the most important hyperparameters

Manual tuning: Use insight and train-test scores for guidance

Hyperparameter optimization: be careful not to over-tune