Basics of modeling, optimization, and regularization

Joaquin Vanschoren

Source

# Auto-setup when running on Google Colab

import os

if 'google.colab' in str(get_ipython()) and not os.path.exists('/content/master'):

!git clone -q https://github.com/ML-course/master.git /content/master

!pip --quiet install -r /content/master/requirements_colab.txt

%cd master/notebooks

# Global imports and settings

%matplotlib inline

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

from preamble import *

interactive = False # Set to True for interactive plots

if interactive:

fig_scale = 0.3

plt.rcParams.update(print_config)

else: # For printing

fig_scale = 0.3

plt.rcParams.update(print_config)Notation and Definitions¶

A scalar is a simple numeric value, denoted by an italic letter:

A vector is a 1D ordered array of n scalars, denoted by a bold letter:

denotes the th element of a vector, thus .

Note: some other courses use notation

A set is an unordered collection of unique elements, denote by caligraphic capital:

A matrix is a 2D array of scalars, denoted by bold capital:

denotes the th row of the matrix

denotes the th column

denotes the element in the th row, th column, thus

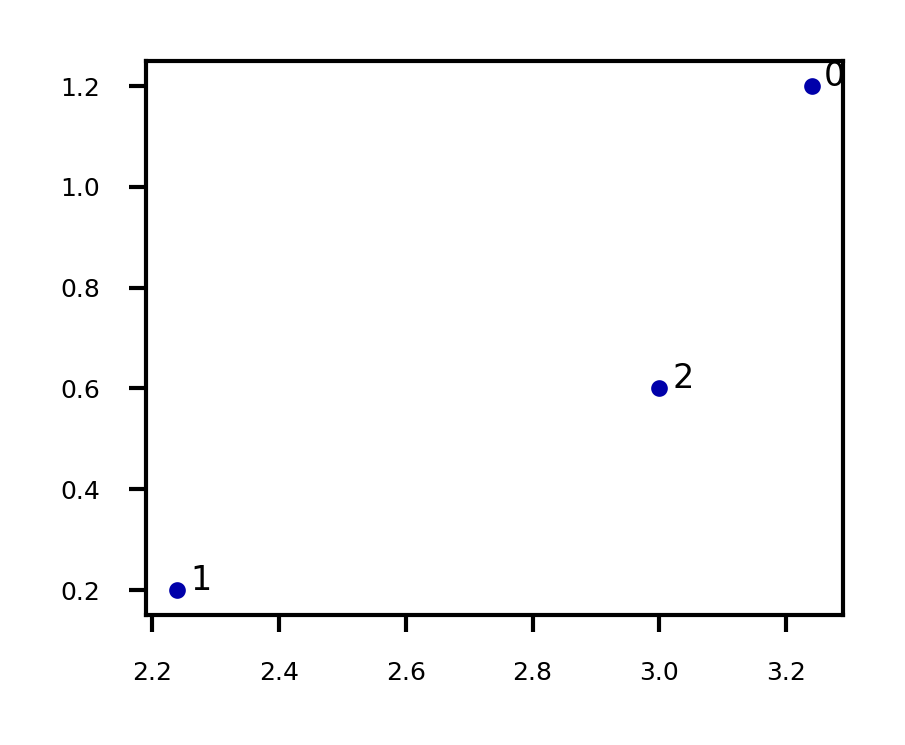

, an matrix, can represent data points in a -dimensional space

Every row is a vector that can represent a point in an p-dimensional space, given a basis.

The standard basis for a Euclidean space is the set of unit vectors

E.g. if

Source

X = np.array([[3.24 , 1.2 ],[2.24, 0.2],[3.0 , 0.6 ]])

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plt.scatter(X[:,0],X[:,1]);

for i in range(3):

plt.annotate(i, (X[i,0]+0.02, X[i,1]))

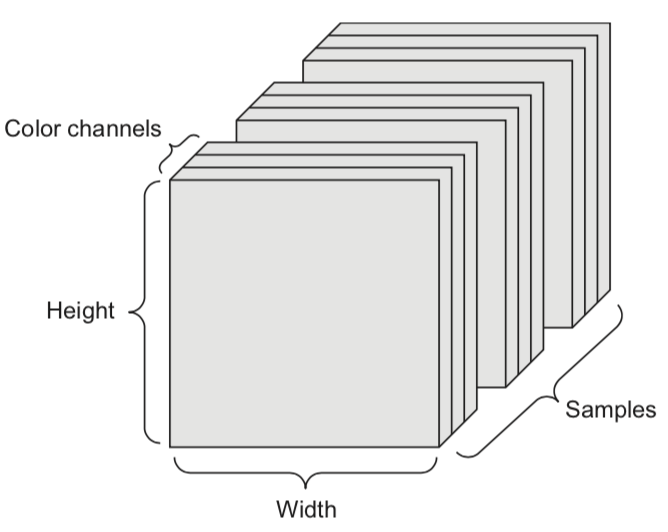

A tensor is an k-dimensional array of data, denoted by an italic capital:

k is also called the order, degree, or rank

denotes the element or sub-tensor in the corresponding position

A set of color images can be represented by:

a 4D tensor (sample x height x width x color channel)

a 2D tensor (sample x flattened vector of pixel values)

Basic operations¶

Sums and products are denoted by capital Sigma and capital Pi:

Operations on vectors are element-wise: e.g.

Dot product

Matrix product

A function relates an input element to an output

It has a local minimum at if in interval

It has a global minimum at if for any value for

A vector function consumes an input and produces a vector:

returns the largest value f(x) for any x

returns the element x that maximizes f(x)

Gradients¶

A derivative of a function describes how fast grows or decreases

The process of finding a derivative is called differentiation

Derivatives for basic functions are known

For non-basic functions we use the chain rule:

A function is differentiable if it has a derivative in any point of it’s domain

It’s continuously differentiable if is a continuous function

We say is smooth if it is infinitely differentiable, i.e., all exist

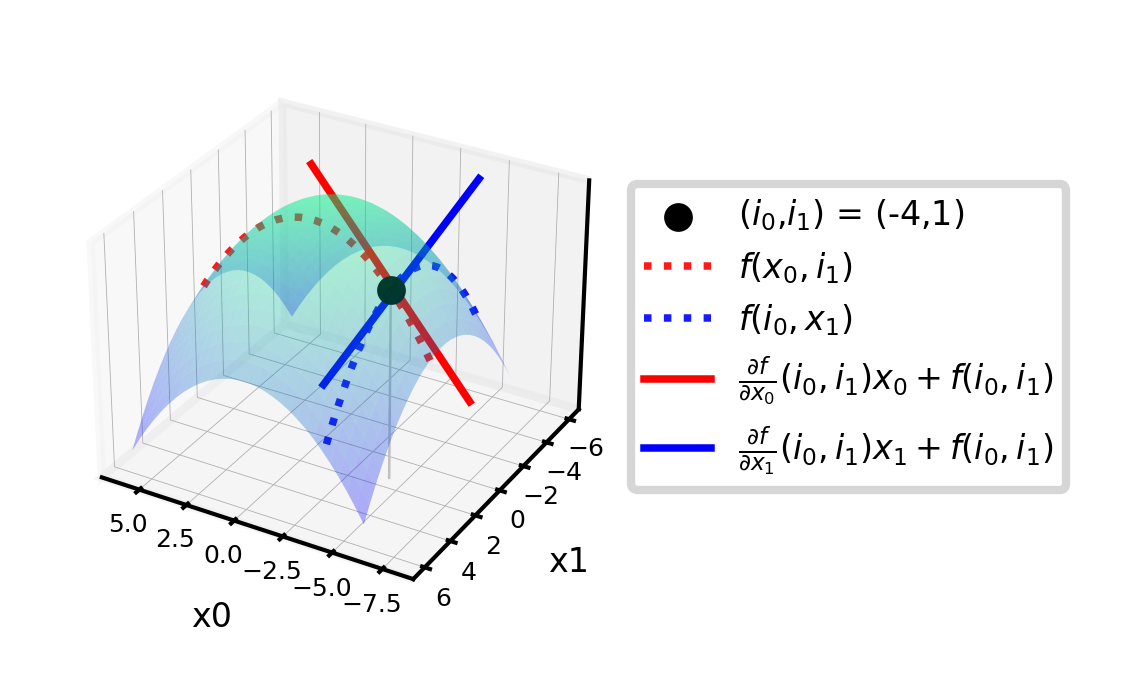

A gradient is the derivative of a function in multiple dimensions

It is a vector of partial derivatives:

E.g.

Example:

Evaluated at point (-4,1):

These are the slopes at point (-4,1) in the direction of and respectively

Source

from mpl_toolkits import mplot3d

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interact_manual

# f = -(x0^2 + x1^2)

def g_f(x0, x1):

return -(x0 ** 2 + x1 ** 2)

def g_dfx0(x0):

return -2 * x0

def g_dfx1(x1):

return -2 * x1

@interact

def plot_gradient(rotation=(0,240,10)):

# plot surface of f

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12*fig_scale,5*fig_scale))

ax = plt.axes(projection="3d")

x0 = np.linspace(-6, 6, 30)

x1 = np.linspace(-6, 6, 30)

X0, X1 = np.meshgrid(x0, x1)

ax.plot_surface(X0, X1, g_f(X0, X1), rstride=1, cstride=1,

cmap='winter', edgecolor='none',alpha=0.3)

# choose point to evaluate: (-4,1)

i0 = -4

i1 = 1

iz = np.linspace(g_f(i0,i1), -82, 30)

ax.scatter3D(i0, i1, g_f(i0,i1), c="k", s=20*fig_scale,label='($i_0$,$i_1$) = (-4,1)')

ax.plot3D([i0]*30, [i1]*30, iz, linewidth=1*fig_scale, c='silver', linestyle='-')

ax.set_zlim(-80,0)

# plot intersects

ax.plot3D(x0,[1]*30,g_f(x0, 1),linewidth=3*fig_scale,alpha=0.9,label='$f(x_0,i_1)$',c='r',linestyle=':')

ax.plot3D([-4]*30,x1,g_f(-4, x1),linewidth=3*fig_scale,alpha=0.9,label='$f(i_0,x_1)$',c='b',linestyle=':')

# df/dx0 is slope of line at the intersect point

x0 = np.linspace(-8, 0, 30)

ax.plot3D(x0,[1]*30,g_dfx0(i0)*x0-g_f(i0,i1),linewidth=3*fig_scale,label=r'$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_0}(i_0,i_1) x_0 + f(i_0,i_1)$',c='r',linestyle='-')

ax.plot3D([-4]*30,x1,g_dfx1(i1)*x1+g_f(i0,i1),linewidth=3*fig_scale,label=r'$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x_1}(i_0,i_1) x_1 + f(i_0,i_1)$',c='b',linestyle='-')

ax.set_xlabel('x0', labelpad=-4/fig_scale)

ax.set_ylabel('x1', labelpad=-4/fig_scale)

ax.get_zaxis().set_ticks([])

ax.view_init(30, rotation) # Use this to rotate the figure

ax.legend()

box = ax.get_position()

ax.set_position([box.x0, box.y0, box.width * 0.8, box.height])

ax.legend(loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1, 0.5))

ax.tick_params(axis='both', width=0, labelsize=10*fig_scale, pad=-6)

#plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_gradient(rotation=120)

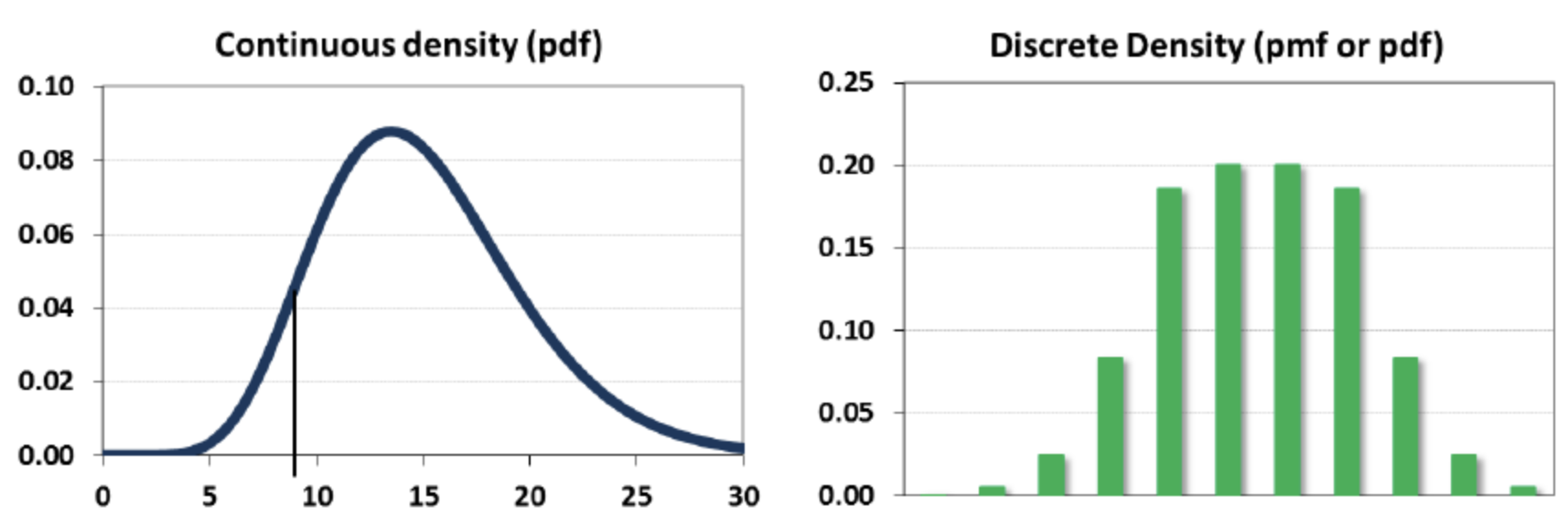

Distributions and Probabilities¶

The normal (Gaussian) distribution with mean and standard deviation is noted as

A random variable can be continuous or discrete

A probability distribution of a continuous variable : probability density function (pdf)

The expectation is given by

A probability distribution of a discrete variable: probability mass function (pmf)

The expectation (or mean)

Linear models¶

Linear models make a prediction using a linear function of the input features

Learn from , given a loss function :

Many algorithms with different : Least squares, Ridge, Lasso, Logistic Regression, Linear SVMs,...

Can be very powerful (and fast), especially for large datasets with many features.

Can be generalized to learn non-linear patterns: Generalized Linear Models

Features can be augmentented with polynomials of the original features

Features can be transformed according to a distribution (Poisson, Tweedie, Gamma,...)

Some linear models (e.g. SVMs) can be kernelized to learn non-linear functions

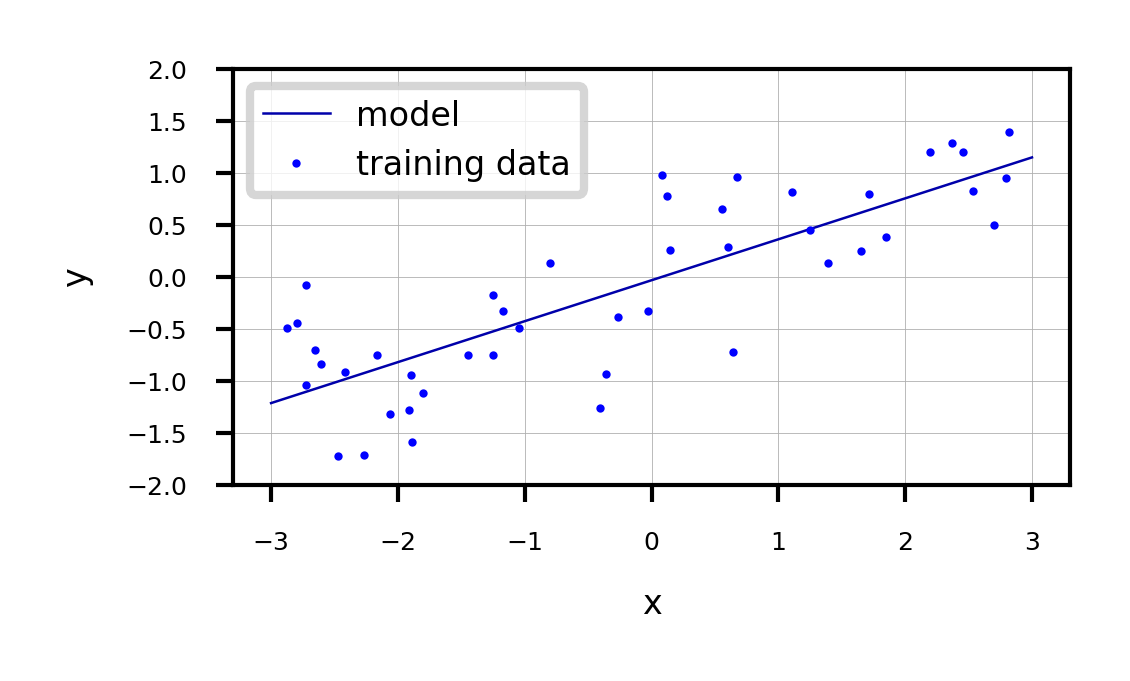

Linear models for regression¶

Prediction formula for input features x:

... usually called weights or coefficients , the bias or intercept

Assumes that errors are

Source

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from mglearn.datasets import make_wave

Xw, yw = make_wave(n_samples=60)

Xw_train, Xw_test, yw_train, yw_test = train_test_split(Xw, yw, random_state=42)

line = np.linspace(-3, 3, 100).reshape(-1, 1)

lr = LinearRegression().fit(Xw_train, yw_train)

print("w_1: %f w_0: %f" % (lr.coef_[0], lr.intercept_))

plt.figure(figsize=(6*fig_scale, 3*fig_scale))

plt.plot(line, lr.predict(line), lw=fig_scale)

plt.plot(Xw_train, yw_train, 'o', c='b')

#plt.plot(X_test, y_test, '.', c='r')

ax = plt.gca()

ax.grid(True)

ax.set_ylim(-2, 2)

ax.set_xlabel('x')

ax.set_ylabel('y')

ax.legend(["model", "training data"], loc="best");w_1: 0.393906 w_0: -0.031804

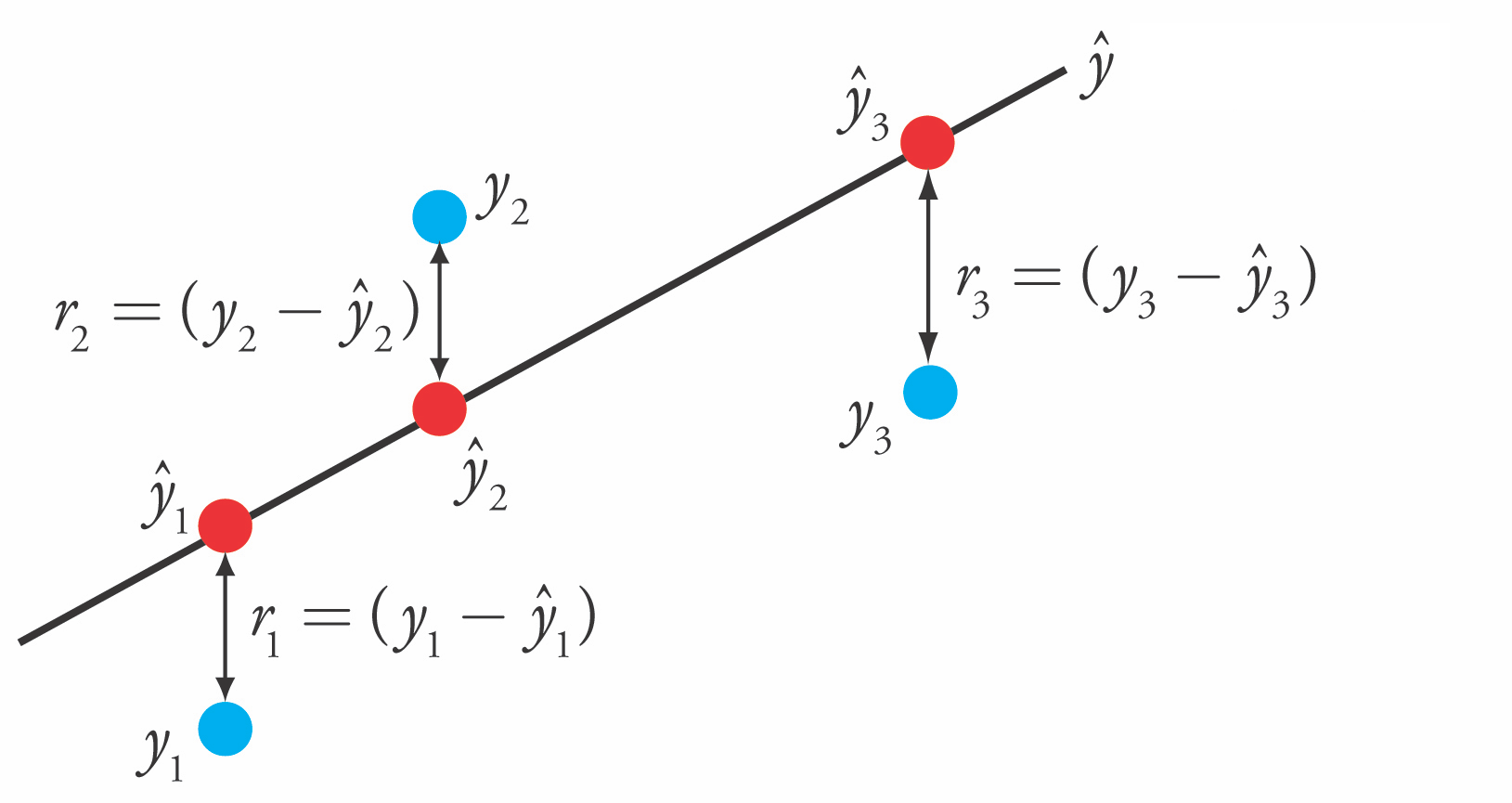

Linear Regression (aka Ordinary Least Squares)¶

Loss function is the sum of squared errors (SSE) (or residuals) between predictions (red) and the true regression targets (blue) on the training set.

Solving ordinary least squares¶

Convex optimization problem with unique closed-form solution:

Add a column of 1’s to the front of X to get

Slow. Time complexity is quadratic in number of features:

X has rows, features, hence has dimensionality

Only works if

Gradient Descent

Faster for large and/or high-dimensional datasets

When cannot be computed or takes too long ( or is too large)

When you want more control over the learning process

Very easily overfits.

coefficients become very large (steep incline/decline)

small change in the input x results in a very different output y

No hyperparameters that control model complexity

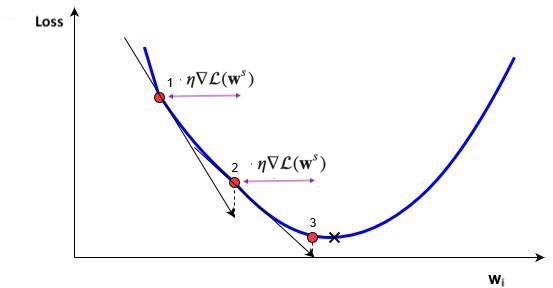

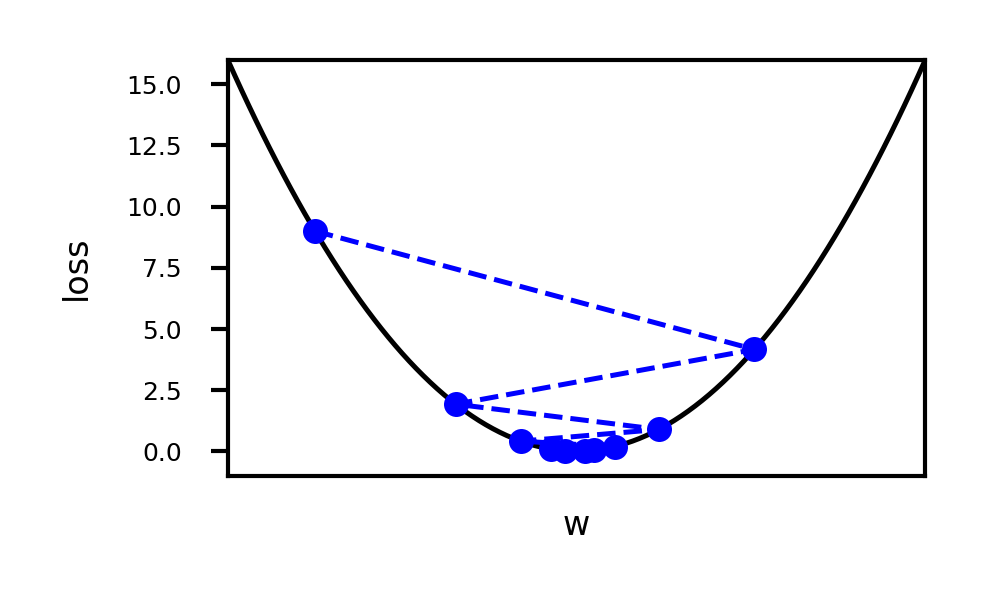

Gradient Descent¶

Start with an initial, random set of weights:

Given a differentiable loss function (e.g. ), compute

For least squares:

If feature is associated with big errors, the gradient wrt will be large

Update all weights slightly (by step size or learning rate ) in ‘downhill’ direction.

Basic update rule (step s):

Important hyperparameters

Learning rate

Too small: slow convergence. Too large: possible divergence

Maximum number of iterations

Too small: no convergence. Too large: wastes resources

Learning rate decay with decay rate

E.g. exponential (), inverse-time (),...

Many more advanced ways to control learning rate (see later)

Adaptive techniques: depend on how much loss improved in previous step

Source

import math

# Some convex function to represent the loss

def l_fx(x):

return (x * 4)**2

# Derivative to compute the gradient

def l_dfx0(x0):

return 8 * x0

@interact

def plot_learning_rate(learn_rate=(0.01,0.4,0.01), exp_decay=False):

w = np.linspace(-1,1,101)

f = [l_fx(i) for i in w]

w_current = -0.75

learn_rate_current = learn_rate

fw = [] # weight values

fl = [] # loss values

for i in range(10):

fw.append(w_current)

fl.append(l_fx(w_current))

# Decay

if exp_decay:

learn_rate_current = learn_rate * math.exp(-0.3*i)

# Update rule

w_current = w_current - learn_rate_current * l_dfx0(w_current)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(5*fig_scale,3*fig_scale))

ax.set_xlabel('w')

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_ylabel('loss')

ax.plot(w, f, lw=2*fig_scale, ls='-', c='k', label='Loss')

ax.plot(fw, fl, '--bo', lw=2*fig_scale, markersize=3)

plt.ylim(-1,16)

plt.xlim(-1,1)

plt.show()

Source

if not interactive:

plot_learning_rate(learn_rate=0.21, exp_decay=False)

import torch

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.colors import LogNorm

from ipywidgets import interact, interactive

# 1. Setup Device (GPU if available)

if torch.cuda.is_available(): # For CUDA based systems

device = torch.device("cuda")

if torch.backends.mps.is_available(): # For MPS (M1-M4 Mac) based systems

device = torch.device("mps")

# print(f"Used device: {device}")

# Toy surface (Beale function)

def f(x, y):

return (1.5 - x + x*y)**2 + (2.25 - x + x*y**2)**2 + (2.625 - x + x*y**3)**2

opt_names = ['sgd', 'sgd_decay']

cmap = plt.cm.get_cmap('tab10')

colors = [cmap(x/10) for x in range(10)]

# --- Training Loop 1: Compare Optimizers ---

all_paths = []

for name in opt_names:

# Initialize variables on GPU

x = torch.tensor(0.8, device=device, requires_grad=True)

y = torch.tensor(1.6, device=device, requires_grad=True)

# Initialize Optimizer

# Note: PyTorch optimizers need the parameters passed at creation.

lr = 0.01

if name == 'sgd':

opt = torch.optim.SGD([x, y], lr=lr)

scheduler = None

elif name == 'sgd_decay':

opt = torch.optim.SGD([x, y], lr=0.02)

# Emulate TF ExponentialDecay: decay_rate^(step/decay_steps).

# For per-step updates, gamma = decay_rate^(1/decay_steps)

gamma = 0.96**(1/100)

scheduler = torch.optim.lr_scheduler.ExponentialLR(opt, gamma=gamma)

x_history = []

y_history = []

z_prev = 0.0

max_steps = 100

for step in range(max_steps):

# 1. Forward pass

z = f(x, y)

# 2. Record history (Move to CPU/Numpy)

x_history.append(x.detach().cpu().item())

y_history.append(y.detach().cpu().item())

# Check convergence

if np.abs(z_prev - z.detach().cpu().item()) < 1e-6:

break

z_prev = z.detach().cpu().item()

# 3. Backward pass and Optimization

opt.zero_grad() # Clear previous gradients

z.backward() # Compute gradients

opt.step() # Update parameters

if scheduler:

scheduler.step()

# Process path for plotting

x_history = np.array(x_history)

y_history = np.array(y_history)

path = np.concatenate((np.expand_dims(x_history, 1), np.expand_dims(y_history, 1)), axis=1).T

all_paths.append(path)

# --- Plotting Setup ---

# (Calculations done on CPU for easier Matplotlib integration)

number_of_points = 50

minima = np.array([3., .5])

x_min, x_max = -2, 3.5

y_min, y_max = -3.5, 2

x_points = np.linspace(x_min, x_max, number_of_points)

y_points = np.linspace(y_min, y_max, number_of_points)

x_mesh, y_mesh = np.meshgrid(x_points, y_points)

# Calculate Z mesh (pure numpy is sufficient for grid generation)

z_grid = np.array([f(xps, yps) for xps, yps in zip(x_mesh, y_mesh)])

def plot_optimizers(ax, iterations, optimizers_to_show):

ax.contour(x_mesh, y_mesh, z_grid, levels=np.logspace(-0.5, 5, 25), norm=LogNorm(), cmap=plt.cm.jet, linewidths=fig_scale, zorder=-1)

ax.plot(*minima, 'r*', markersize=20*fig_scale)

for name, path, color in zip(opt_names, all_paths, colors):

if name in optimizers_to_show:

p = path[:, :iterations]

if p.shape[1] > 0: # Ensure we have data

ax.plot([], [], color=color, label=name, lw=3*fig_scale, linestyle='-')

if p.shape[1] > 1:

ax.quiver(p[0,:-1], p[1,:-1], p[0,1:]-p[0,:-1], p[1,1:]-p[1,:-1], scale_units='xy', angles='xy', scale=1, color=color, lw=4)

ax.set_xlim((x_min, x_max))

ax.set_ylim((y_min, y_max))

ax.legend(loc='lower left', prop={'size': 15*fig_scale})

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.tight_layout()

# --- Training Loop 2: Learning Rate Sweep ---

all_lr_paths = []

lr_range = [0.005 * i for i in range(1, 11)] # Adjusted range slightly to avoid 0.0

for lr in lr_range:

# Re-init variables on GPU

x = torch.tensor(0.8, device=device, requires_grad=True)

y = torch.tensor(1.6, device=device, requires_grad=True)

# Init Optimizer

opt = torch.optim.SGD([x, y], lr=lr)

x_history = []

y_history = []

z_prev = 0.0

max_steps = 100

for step in range(max_steps):

z = f(x, y)

x_history.append(x.detach().cpu().item())

y_history.append(y.detach().cpu().item())

if np.abs(z_prev - z.detach().cpu().item()) < 1e-6:

break

z_prev = z.detach().cpu().item()

opt.zero_grad()

z.backward()

opt.step()

x_history = np.array(x_history)

y_history = np.array(y_history)

path = np.vstack((x_history, y_history))

all_lr_paths.append(path)

# --- Plotting LR Sweep ---

def plot_learning_rate_optimizers(ax, iterations, lr):

ax.contour(x_mesh, y_mesh, z_grid, levels=np.logspace(-0.5, 5, 25), norm=LogNorm(), cmap=plt.cm.jet, linewidths=1, zorder=-1)

ax.plot(*minima, 'r*', markersize=20)

for path, lrate in zip(all_lr_paths, lr_range):

# Comparison with tolerance for float equality

if abs(lrate - lr) < 1e-5:

p = path[:, :iterations]

if p.shape[1] > 0:

ax.plot([], [], color='b', label=f"Learning rate {round(lr, 3)}", lw=3, linestyle='-')

if p.shape[1] > 1:

ax.quiver(p[0, :-1], p[1, :-1], p[0, 1:] - p[0, :-1], p[1, 1:] - p[1, :-1], scale_units='xy', angles='xy', scale=1, color='b', lw=4)

ax.set_xlim((x_min, x_max))

ax.set_ylim((y_min, y_max))

ax.legend(loc='lower left', prop={'size': 6})

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.tight_layout()Effect of learning rate

Source

@interact

def plot_lr(iterations=(1, 100, 1), learning_rate=(0.005, 0.045, 0.005)): # Fixed range

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6 * fig_scale, 4 * fig_scale))

plot_learning_rate_optimizers(ax, iterations, learning_rate)

plt.show()

if not interactive:

plot_lr(iterations=50, learning_rate=0.02)Effect of learning rate decay

Source

@interact

def compare_optimizers(iterations=(1,100,1), optimizer1=opt_names, optimizer2=opt_names):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plot_optimizers(ax,iterations,[optimizer1,optimizer2])

plt.show()

if not interactive:

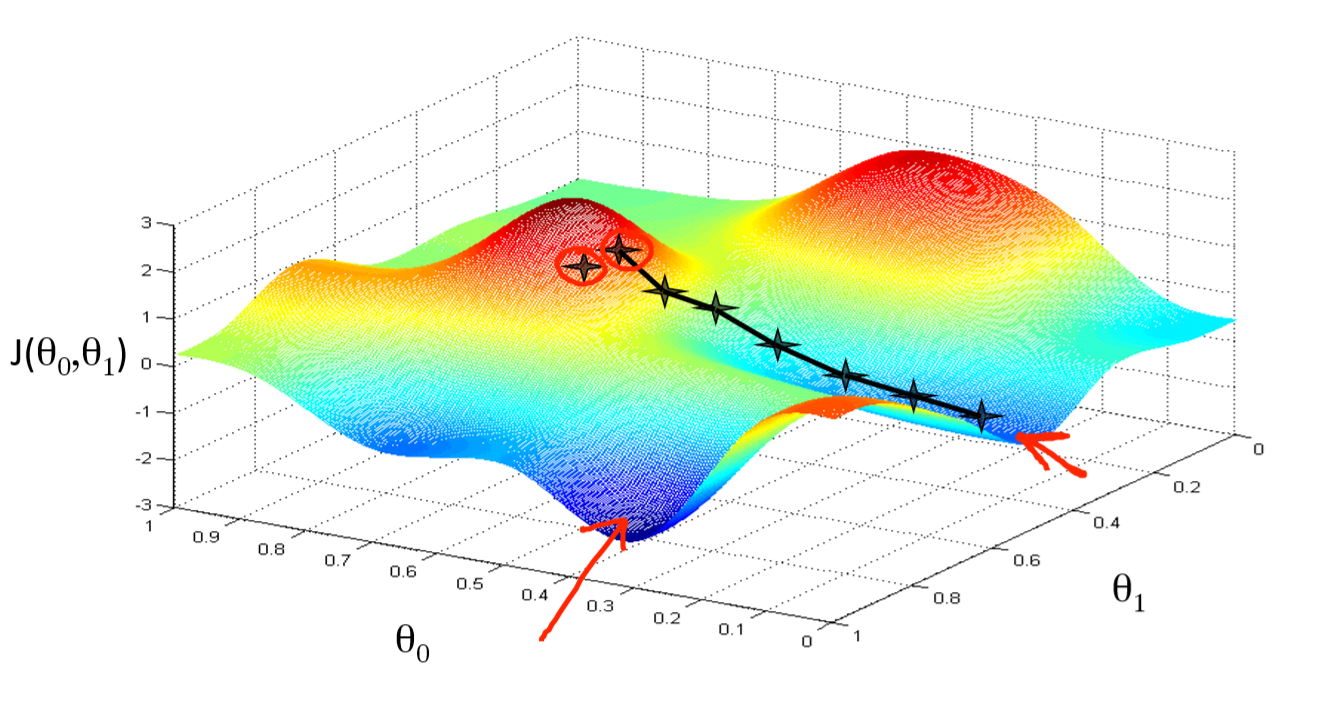

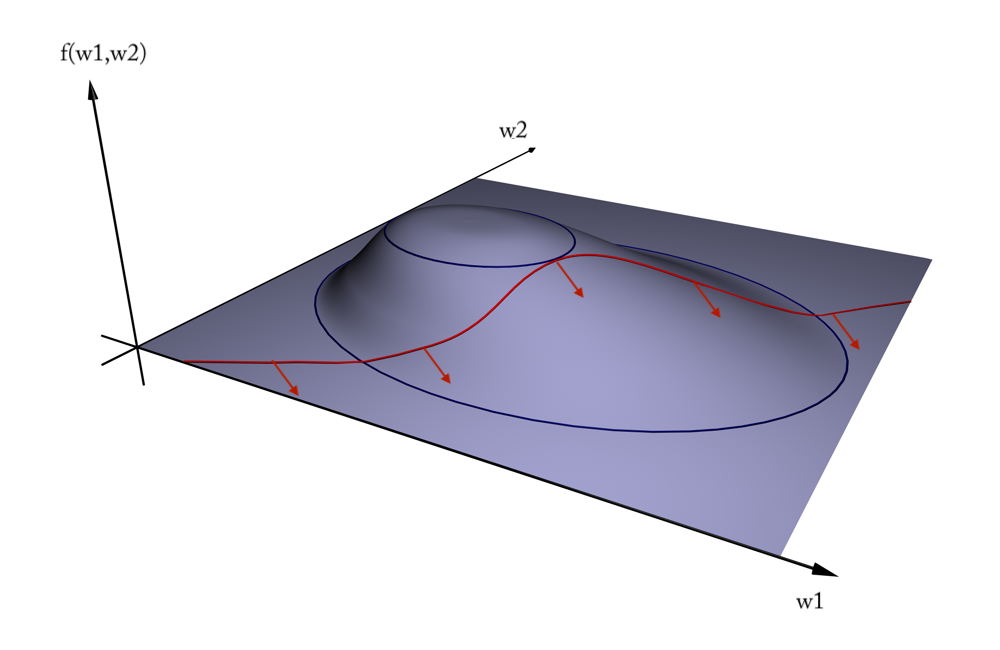

compare_optimizers(iterations=50, optimizer1="sgd", optimizer2="sgd_decay")In two dimensions:

You can get stuck in local minima (if the loss is not fully convex)

If you have many model parameters, this is less likely

You always find a way down in some direction

Models with many parameters typically find good local minima

Intuition: walking downhill using only the slope you “feel” nearby

(Image by A. Karpathy)

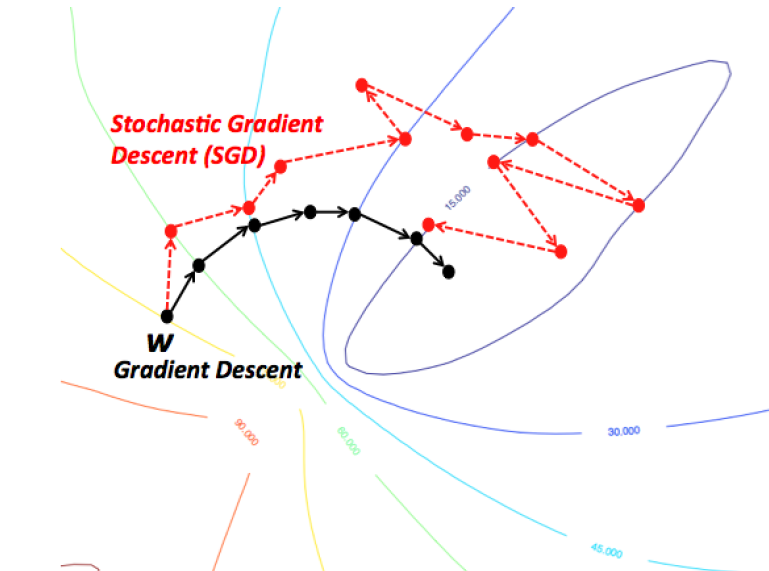

Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD)¶

Compute gradients not on the entire dataset, but on a single data point at a time

Gradient descent:

Stochastic Gradient Descent:

Many smoother variants, e.g.

Minibatch SGD: compute gradient on batches of data:

Stochastic Average Gradient Descent (SAG, SAGA). With randomly chosen per iteration:

Incremental gradient: with

In practice¶

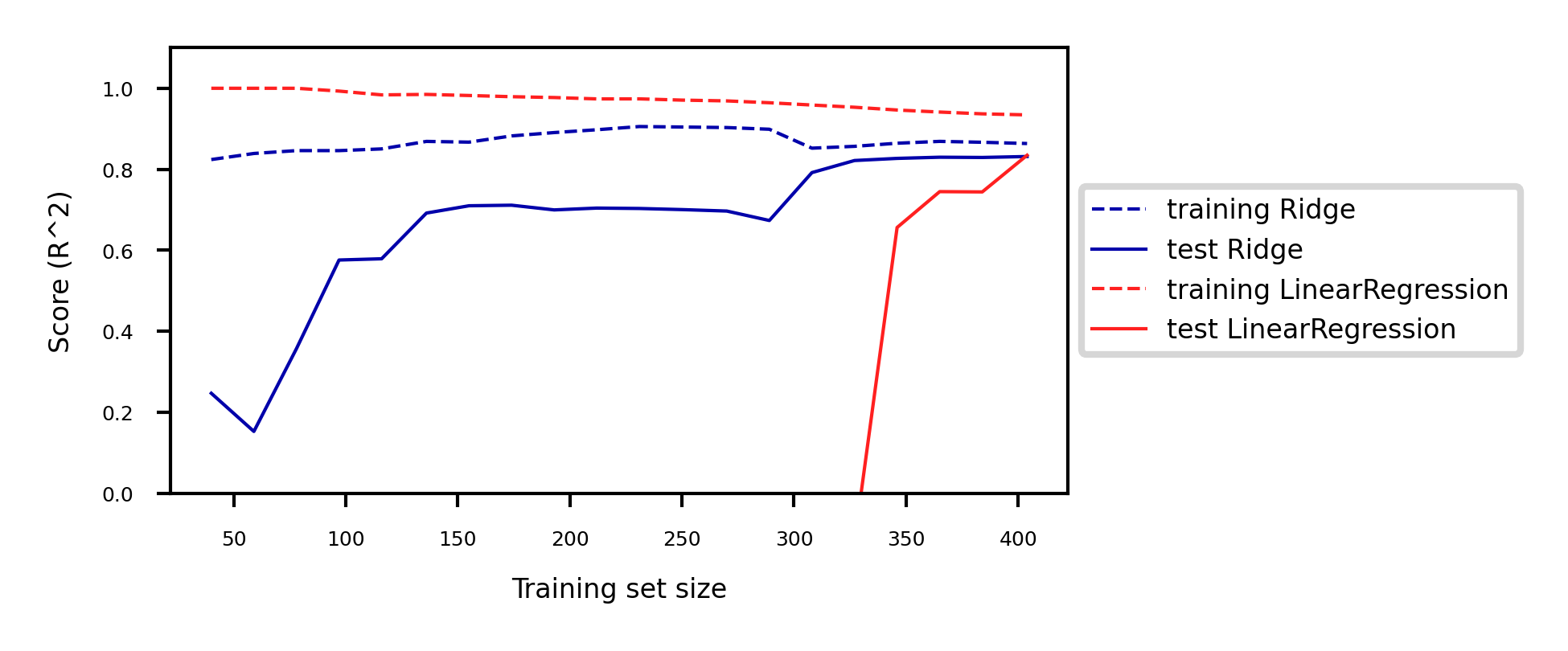

Linear regression can be found in

sklearn.linear_model. We’ll evaluate it on the Boston Housing dataset.LinearRegressionuses closed form solution,SGDRegressorwithloss='squared_loss'uses Stochastic Gradient DescentLarge coefficients signal overfitting

Test score is much lower than training score

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

lr = LinearRegression().fit(X_train, y_train)Source

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

X_B, y_B = mglearn.datasets.load_extended_boston()

X_B_train, X_B_test, y_B_train, y_B_test = train_test_split(X_B, y_B, random_state=0)

lr = LinearRegression().fit(X_B_train, y_B_train)Source

print("Weights (coefficients): {}".format(lr.coef_[0:40]))

print("Bias (intercept): {}".format(lr.intercept_))Weights (coefficients): [ -412.711 -52.243 -131.899 -12.004 -15.511 28.716 54.704

-49.535 26.582 37.062 -11.828 -18.058 -19.525 12.203

2980.781 1500.843 114.187 -16.97 40.961 -24.264 57.616

1278.121 -2239.869 222.825 -2.182 42.996 -13.398 -19.389

-2.575 -81.013 9.66 4.914 -0.812 -7.647 33.784

-11.446 68.508 -17.375 42.813 1.14 ]

Bias (intercept): 30.93456367364383

Source

print("Training set score (R^2): {:.2f}".format(lr.score(X_B_train, y_B_train)))

print("Test set score (R^2): {:.2f}".format(lr.score(X_B_test, y_B_test)))Training set score (R^2): 0.95

Test set score (R^2): 0.61

Ridge regression¶

Adds a penalty term to the least squares loss function:

Model is penalized if it uses large coefficients ()

Each feature should have as little effect on the outcome as possible

We don’t want to penalize , so we leave it out

Regularization: explicitly restrict a model to avoid overfitting.

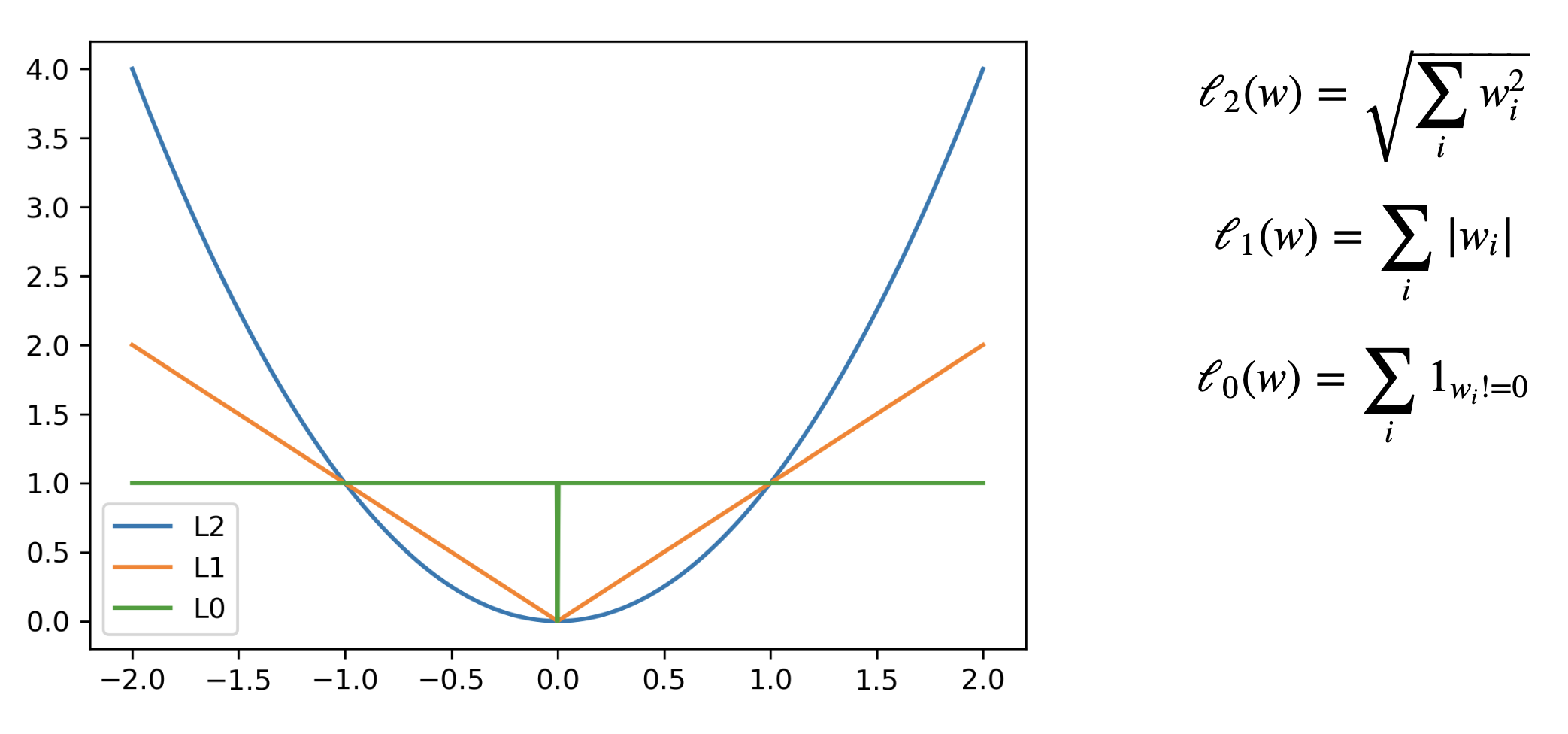

Called L2 regularization because it uses the L2 norm:

The strength of the regularization can be controlled with the hyperparameter.

Increasing causes more regularization (or shrinkage). Default is 1.0.

Still convex. Can be optimized in different ways:

Closed form solution (a.k.a. Cholesky):

Gradient descent and variants, e.g. Stochastic Average Gradient (SAG,SAGA)

Conjugate gradient (CG): each new gradient is influenced by previous ones

Use Cholesky for smaller datasets, Gradient descent for larger ones

In practice¶

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

lr = Ridge().fit(X_train, y_train)Source

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

ridge = Ridge().fit(X_B_train, y_B_train)

print("Weights (coefficients): {}".format(ridge.coef_[0:40]))

print("Bias (intercept): {}".format(ridge.intercept_))

print("Training set score: {:.2f}".format(ridge.score(X_B_train, y_B_train)))

print("Test set score: {:.2f}".format(ridge.score(X_B_test, y_B_test)))Weights (coefficients): [-1.414 -1.557 -1.465 -0.127 -0.079 8.332 0.255 -4.941 3.899 -1.059

-1.584 1.051 -4.012 0.334 0.004 -0.849 0.745 -1.431 -1.63 -1.405

-0.045 -1.746 -1.467 -1.332 -1.692 -0.506 2.622 -2.092 0.195 -0.275

5.113 -1.671 -0.098 0.634 -0.61 0.04 -1.277 -2.913 3.395 0.792]

Bias (intercept): 21.390525958609953

Training set score: 0.89

Test set score: 0.75

Test set score is higher and training set score lower: less overfitting!

We can plot the weight values for differents levels of regularization to explore the effect of .

Increasing regularization decreases the values of the coefficients, but never to 0.

Source

from __future__ import print_function

import ipywidgets as widgets

from ipywidgets import interact, interact_manual

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge

@interact

def plot_ridge(alpha=(0,10.0,0.05)):

r = Ridge(alpha=alpha).fit(X_B_train, y_B_train)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,1.5*fig_scale))

ax.plot(r.coef_, 'o', markersize=3)

ax.set_title("alpha {}, test score {:.2f} (training score {:.2f})".format(alpha, r.score(X_B_test, y_B_test), r.score(X_B_train, y_B_train)))

ax.set_xlabel("Coefficient index")

ax.set_ylabel("Coefficient magnitude")

ax.hlines(0, 0, len(r.coef_))

ax.set_ylim(-25, 25)

ax.set_xlim(0, 50);

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

for alpha in [0.1, 10]:

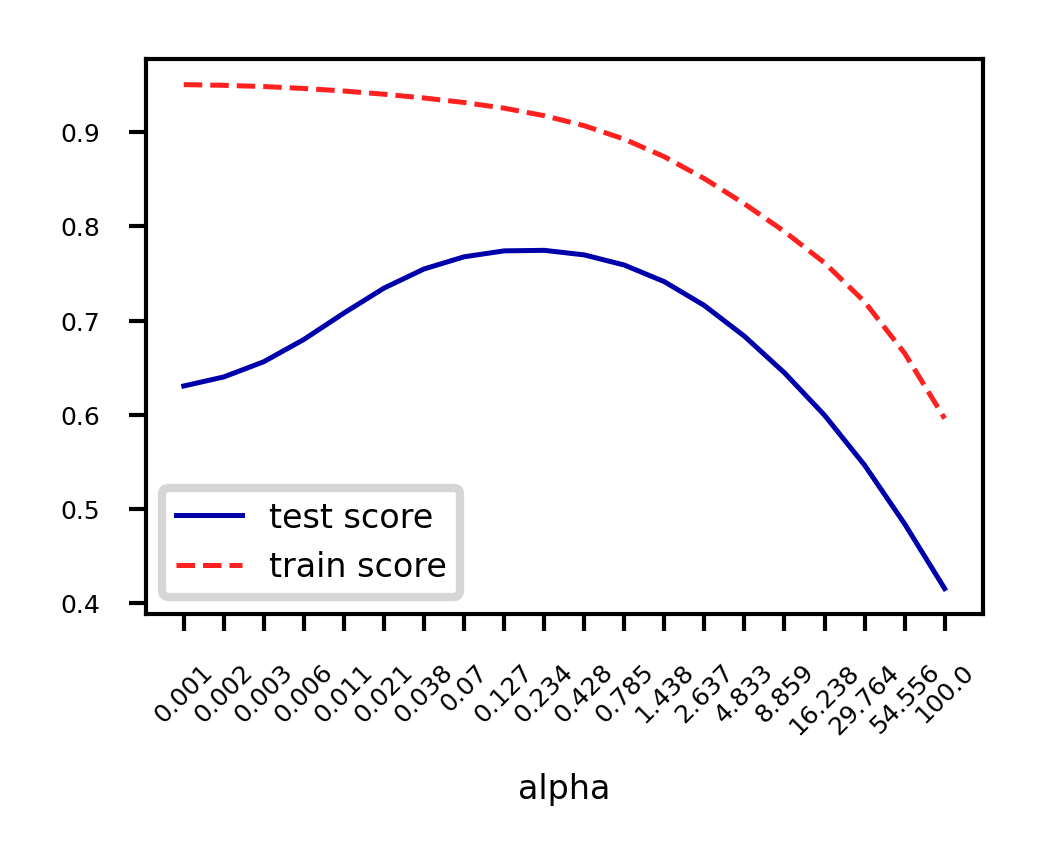

plot_ridge(alpha)When we plot the train and test scores for every value, we see a sweet spot around

Models with smaller are overfitting

Models with larger are underfitting

Source

alpha=np.logspace(-3,2,num=20)

ai = list(range(len(alpha)))

test_score=[]

train_score=[]

for a in alpha:

r = Ridge(alpha=a).fit(X_B_train, y_B_train)

test_score.append(r.score(X_B_test, y_B_test))

train_score.append(r.score(X_B_train, y_B_train))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

ax.set_xticks(range(20))

ax.set_xticklabels(np.round(alpha,3))

ax.set_xlabel('alpha')

ax.plot(test_score, lw=2*fig_scale, label='test score')

ax.plot(train_score, lw=2*fig_scale, label='train score')

ax.legend()

plt.xticks(rotation=45);

Other ways to reduce overfitting¶

Add more training data: with enough training data, regularization becomes less important

Ridge and ordinary least squares will have the same performance

Use fewer features: remove unimportant ones or find a low-dimensional embedding (e.g. PCA)

Fewer coefficients to learn, reduces the flexibility of the model

Scaling the data typically helps (and changes the optimal value)

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

mglearn.plots.plot_ridge_n_samples(ax)

Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator)¶

Adds a different penalty term to the least squares sum:

Called L1 regularization because it uses the L1 norm

Will cause many weights to be exactly 0

Same parameter to control the strength of regularization.

Will again have a ‘sweet spot’ depending on the data

No closed-form solution

Convex, but no longer strictly convex, and not differentiable

Weights can be optimized using coordinate descent

Analyze what happens to the weights:

L1 prefers coefficients to be exactly zero (sparse models)

Some features are ignored entirely: automatic feature selection

How can we explain this?

Source

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

@interact

def plot_lasso(alpha=(0,0.5,0.005)):

r = Lasso(alpha=alpha).fit(X_B_train, y_B_train)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,1.5*fig_scale))

ax.plot(r.coef_, 'o', markersize=6*fig_scale)

ax.set_title("alpha {}, score {:.2f} (training score {:.2f})".format(alpha, r.score(X_B_test, y_B_test), r.score(X_B_train, y_B_train)), pad=0.5)

ax.set_xlabel("Coefficient index", labelpad=0)

ax.set_ylabel("Coefficient magnitude")

ax.hlines(0, 0, len(r.coef_))

ax.set_ylim(-25, 25);

ax.set_xlim(0, 50);

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

for alpha in [0.00001, 0.01]:

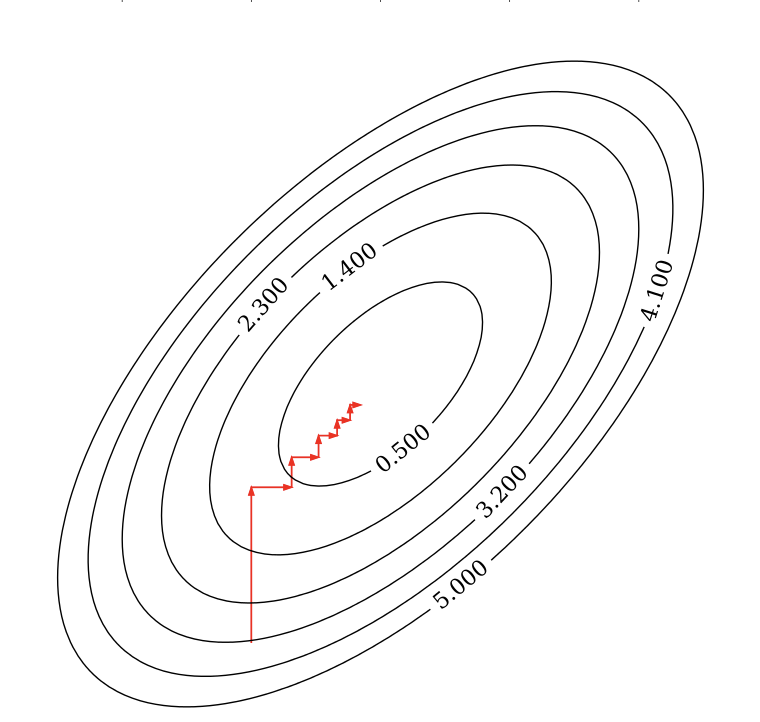

plot_lasso(alpha)Coordinate descent¶

Alternative for gradient descent, supports non-differentiable convex loss functions (e.g. )

In every iteration, optimize a single coordinate (find minimum in direction of )

Continue with another coordinate, using a selection rule (e.g. round robin)

Faster iterations. No need to choose a step size (learning rate).

May converge more slowly. Can’t be parallellized.

Coordinate descent with Lasso¶

Remember that

For one :

The L1 term is not differentiable but convex: we can compute the subgradient

Unique at points where is differentiable, a range of all possible slopes [a,b] where it is not

For , the subgradient =

Subdifferential if and are both convex

To find the optimum for Lasso , solve

In which is the part of excluding (assume for now)

can be seen as the ‘solution’: if

We found:

The Lasso solution has the form of a soft thresholding function

Small weights (all weights between and ) become 0: sparseness!

If the data is not normalized, with constant

Ridge solution: , thus

Source

@interact

def plot_rho(alpha=(0,2.0,0.05)):

w = np.linspace(-2,2,101)

r = w/(1+2*alpha)

l = [x+alpha if x <= -alpha else (x-alpha if x > alpha else 0) for x in w]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,3*fig_scale))

ax.set_xlabel(r'$\rho$')

ax.set_ylabel(r'$w^{*}$')

ax.plot(w, w, lw=2*fig_scale, c='g', label='Ordinary Least Squares (SSE)')

ax.plot(w, r, lw=2*fig_scale, c='b', label='Ridge with alpha={}'.format(alpha))

ax.plot(w, l, lw=2*fig_scale, c='r', label='Lasso with alpha={}'.format(alpha))

ax.legend()

plt.grid()

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_rho(alpha=1)Least Squares Loss + L1 or L2

The Lasso curve has 3 parts (,,) corresponding to the thresholding function

For any minimum of least squares, L2 will be smaller, and L1 is more likely be exactly 0

Source

def c_fx(x):

fX = ((x * 2 - 1)**2) # Some convex function to represent the loss

return fX/9 # Scaling

def c_fl2(x,alpha):

return c_fx(x) + alpha * x**2

def c_fl1(x,alpha):

return c_fx(x) + alpha * abs(x)

def l2(x,alpha):

return alpha * x**2

def l1(x,alpha):

return alpha * abs(x)

@interact

def plot_losses(alpha=(0,1.0,0.05)):

w = np.linspace(-1,1,101)

f = [c_fx(i) for i in w]

r = [c_fl2(i,alpha) for i in w]

l = [c_fl1(i,alpha) for i in w]

rp = [l2(i,alpha) for i in w]

lp = [l1(i,alpha) for i in w]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

ax.set_xlabel('w')

ax.set_ylabel('loss')

ax.plot(w, rp, lw=1.5*fig_scale, ls=':', c='b', label='L2 with alpha={}'.format(alpha))

ax.plot(w, lp, lw=1.5*fig_scale, ls=':', c='r', label='L1 with alpha={}'.format(alpha))

ax.plot(w, f, lw=2*fig_scale, ls='-', c='k', label='Least Squares loss')

ax.plot(w, r, lw=2*fig_scale, ls='-', c='b', label='Loss + L2 (Ridge)'.format(alpha))

ax.plot(w, l, lw=2*fig_scale, ls='-', c='r', label='Loss + L1 (Lasso)'.format(alpha))

opt_f = np.argmin(f)

ax.scatter(w[opt_f], f[opt_f], c="k", s=50*fig_scale)

opt_r = np.argmin(r)

ax.scatter(w[opt_r], r[opt_r], c="b", s=50*fig_scale)

opt_l = np.argmin(l)

ax.scatter(w[opt_l], l[opt_l], c="r", s=50*fig_scale)

ax.legend()

box = ax.get_position()

ax.set_position([box.x0, box.y0, box.width * 0.8, box.height])

ax.legend(loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1, 0.5))

plt.ylim(-0.1,1)

plt.grid()

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

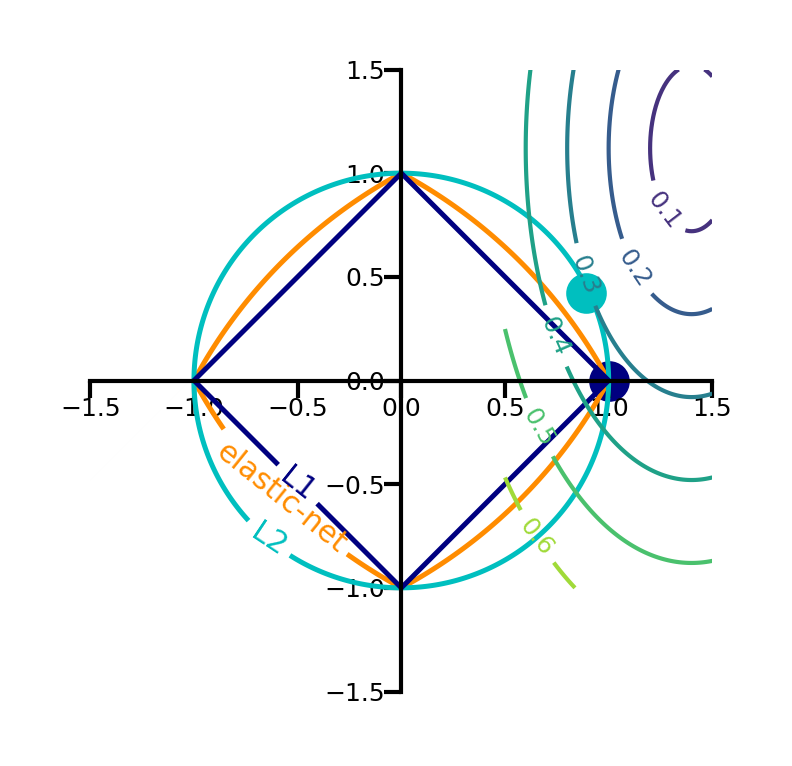

plot_losses(alpha=0.5)In 2D (for 2 model weights and )

The least squared loss is a 2D convex function in this space (ellipses on the right)

For illustration, assume that L1 loss = L2 loss = 1

L1 loss (): the optimal {} (blue dot) falls on the diamond

L2 loss (): the optimal {} (cyan dot) falls on the circle

For L1, the loss is minimized if or is 0 (rarely so for L2)

Source

def plot_loss_interpretation():

line = np.linspace(-1.5, 1.5, 1001)

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(line, line)

l2 = xx ** 2 + yy ** 2

l1 = np.abs(xx) + np.abs(yy)

rho = 0.7

elastic_net = rho * l1 + (1 - rho) * l2

plt.figure(figsize=(5*fig_scale, 4*fig_scale))

ax = plt.gca()

elastic_net_contour = plt.contour(xx, yy, elastic_net, levels=[1], linewidths=2*fig_scale, colors="darkorange")

l2_contour = plt.contour(xx, yy, l2, levels=[1], linewidths=2*fig_scale, colors="c")

l1_contour = plt.contour(xx, yy, l1, levels=[1], linewidths=2*fig_scale, colors="navy")

ax.set_aspect("equal")

ax.spines['left'].set_position('center')

ax.spines['right'].set_color('none')

ax.spines['bottom'].set_position('center')

ax.spines['top'].set_color('none')

plt.clabel(elastic_net_contour, inline=1, fontsize=12*fig_scale,

fmt={1.0: 'elastic-net'}, manual=[(-0.6, -0.6)])

plt.clabel(l2_contour, inline=1, fontsize=12*fig_scale,

fmt={1.0: 'L2'}, manual=[(-0.5, -0.5)])

plt.clabel(l1_contour, inline=1, fontsize=12*fig_scale,

fmt={1.0: 'L1'}, manual=[(-0.5, -0.5)])

x1 = np.linspace(0.5, 1.5, 100)

x2 = np.linspace(-1.0, 1.5, 100)

X1, X2 = np.meshgrid(x1, x2)

Y = np.sqrt(np.square(X1/2-0.7) + np.square(X2/4-0.28))

cp = plt.contour(X1, X2, Y)

plt.clabel(cp, inline=1, fontsize=3)

ax.tick_params(axis='both', pad=0)

ax.scatter(1, 0, c="navy", s=50*fig_scale)

ax.scatter(0.89, 0.42, c="c", s=50*fig_scale)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

plot_loss_interpretation()

Elastic-Net¶

Adds both L1 and L2 regularization:

is the L1 ratio

With ,

With ,

sets a trade-off between L1 and L2.

Allows learning sparse models (like Lasso) while maintaining L2 regularization benefits

E.g. if 2 features are correlated, Lasso likely picks one randomly, Elastic-Net keeps both

Weights can be optimized using coordinate descent (similar to Lasso)

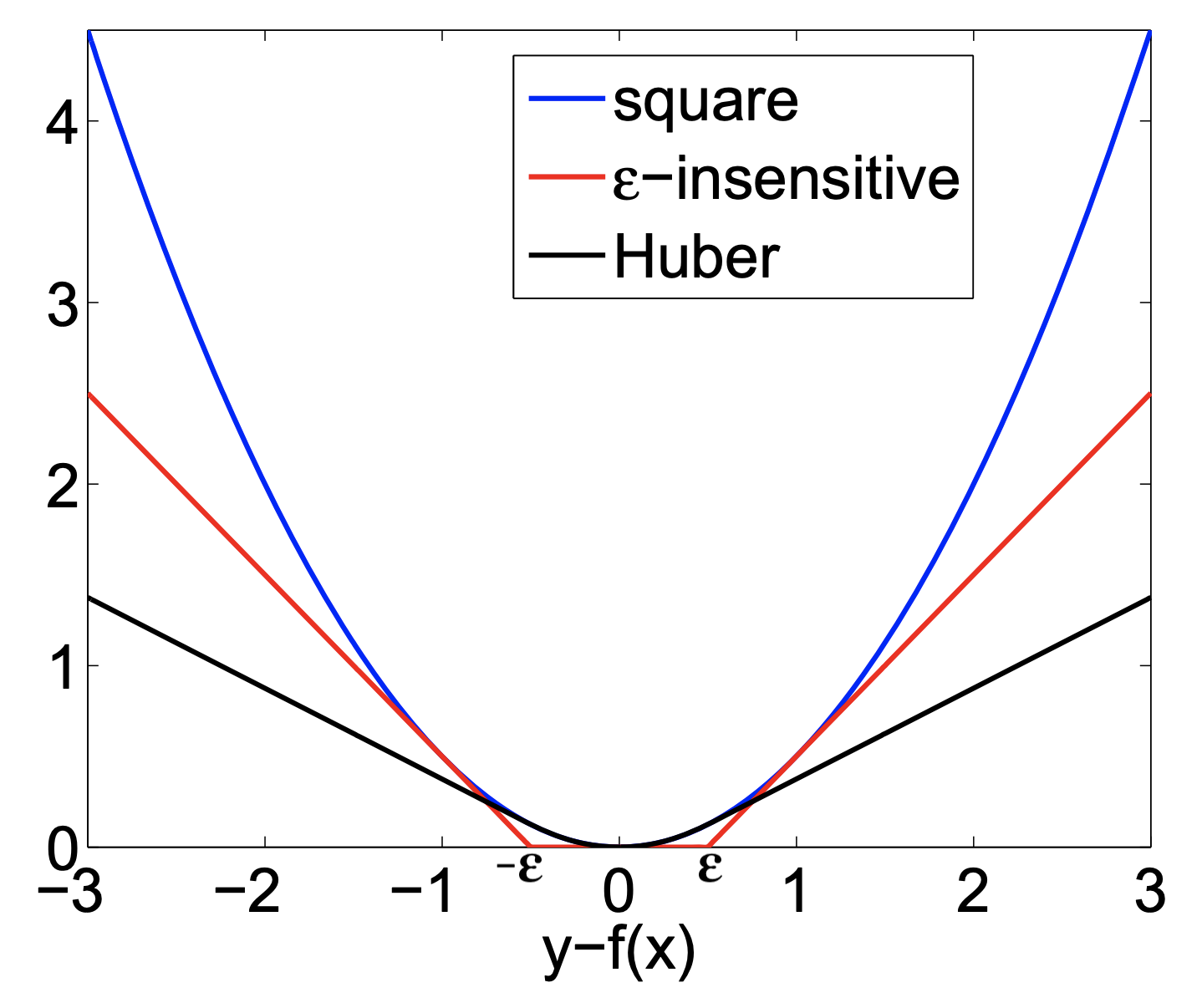

Other loss functions for regression¶

Huber loss: switches from squared loss to linear loss past a value

More robust against outliers

Epsilon insensitive: ignores errors smaller than , and linear past that

Aims to fit function so that residuals are at most

Also known as Support Vector Regression (

SVRin sklearn)

Squared Epsilon insensitive: ignores errors smaller than , and squared past that

These can all be solved with stochastic gradient descent

SGDRegressorin sklearn

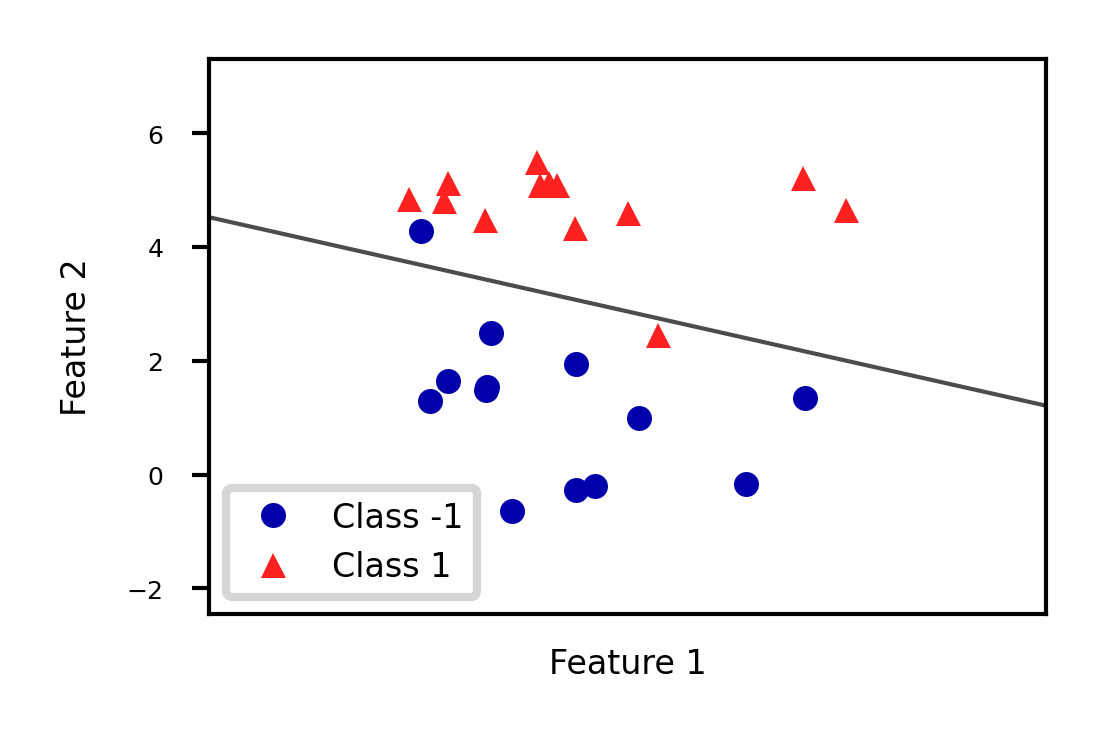

Linear models for Classification¶

Aims to find a hyperplane that separates the examples of each class.

For binary classification (2 classes), we aim to fit the following function:

When , predict class -1, otherwise predict class +1

Source

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.svm import LinearSVC

Xf, yf = mglearn.datasets.make_forge()

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

clf = LogisticRegression().fit(Xf, yf)

mglearn.tools.plot_2d_separator(clf, Xf,

ax=ax, alpha=.7, cm=mglearn.cm2)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xf[:, 0], Xf[:, 1], yf, ax=ax, s=10*fig_scale)

ax.set_xlabel("Feature 1")

ax.set_ylabel("Feature 2")

ax.legend(['Class -1','Class 1']);

There are many algorithms for linear classification, differing in loss function, regularization techniques, and optimization method

Most common techniques:

Convert target classes {neg,pos} to {0,1} and treat as a regression task

Logistic regression (Log loss)

Ridge Classification (Least Squares + L2 loss)

Find hyperplane that maximizes the margin between classes

Linear Support Vector Machines (Hinge loss)

Neural networks without activation functions

Perceptron (Perceptron loss)

SGDClassifier: can act like any of these by choosing loss function

Hinge, Log, Modified_huber, Squared_hinge, Perceptron

Logistic regression¶

Aims to predict the probability that a point belongs to the positive class

Converts target values {negative (blue), positive (red)} to {0,1}

Fits a logistic (or sigmoid or S curve) function through these points

Maps (-Inf,Inf) to a probability [0,1]

E.g. in 1D:

Source

def sigmoid(x,w1,w0):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-(x*w1+w0)))

@interact

def plot_logreg(w0=(-10.0,5.0,1),w1=(-1.0,3.0,0.3)):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,3*fig_scale))

red = [Xf[i, 1] for i in range(len(yf)) if yf[i]==1]

blue = [Xf[i, 1] for i in range(len(yf)) if yf[i]==0]

ax.scatter(red, [1]*len(red), c='r', label='Positive class')

ax.scatter(blue, [0]*len(blue), c='b', label='Negative class')

x = np.linspace(min(-1, -w0/w1),max(6, -w0/w1))

ax.plot(x,sigmoid(x,w1,w0),lw=2*fig_scale,c='g', label='logistic(x*w1+w0)'.format(np.round(w0,2),np.round(w1,2)))

ax.axvline(x=(-w0/w1), ymin=0, ymax=1, label='Decision boundary')

ax.plot(x,x*w1+w0,lw=2*fig_scale,c='k',linestyle=':', label='y=x*w1+w0')

ax.set_xlabel("Feature")

ax.set_ylabel("y")

ax.set_ylim(-0.05,1.05)

ax.legend(loc='center left', bbox_to_anchor=(1, 0.5))

box = ax.get_position()

ax.set_position([box.x0, box.y0, box.width * 0.8, box.height]);

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

# fitted solution

clf2 = LogisticRegression(C=100).fit(Xf[:, 1].reshape(-1, 1), yf)

w0 = clf2.intercept_

w1 = clf2.coef_[0][0]

plot_logreg(w0=w0,w1=w1)Fitted solution to our 2D example:

To get a binary prediction, choose a probability threshold (e.g. 0.5)

Source

lr_clf = LogisticRegression(C=100).fit(Xf, yf)

def sigmoid2d(x1,x2,w0,w1,w2):

return 1 / (1 + np.exp(-(x2*w2+x1*w1+w0)))

@interact

def plot_logistic_fit(rotation=(0,360,10)):

w0 = lr_clf.intercept_

w1 = lr_clf.coef_[0][0]

w2 = lr_clf.coef_[0][1]

# plot surface of f

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7*fig_scale,5*fig_scale))

ax = plt.axes(projection="3d")

x0 = np.linspace(8, 16, 30)

x1 = np.linspace(-1, 6, 30)

X0, X1 = np.meshgrid(x0, x1)

# Surface

ax.plot_surface(X0, X1, sigmoid2d(X0, X1, w0, w1, w2), rstride=1, cstride=1,

cmap='bwr', edgecolor='none',alpha=0.5,label='sigmoid')

# Points

c=['b','r']

ax.scatter3D(Xf[:, 0], Xf[:, 1], yf, c=[c[i] for i in yf], s=10*fig_scale)

# Decision boundary

# x2 = -(x1*w1 + w0)/w2

ax.plot3D(x0,-(x0*w1 + w0)/w2,[0.5]*len(x0), lw=1*fig_scale, c='k', linestyle=':')

z = np.linspace(0, 1, 31)

XZ, Z = np.meshgrid(x0, z)

YZ = -(XZ*w1 + w0)/w2

ax.plot_wireframe(XZ, YZ, Z, rstride=5, lw=1*fig_scale, cstride=5, alpha=0.3, color='k',label='decision boundary')

ax.tick_params(axis='both', width=0, labelsize=10*fig_scale, pad=-4)

ax.set_xlabel('x0', labelpad=-6)

ax.set_ylabel('x1', labelpad=-6)

ax.get_zaxis().set_ticks([])

ax.view_init(30, rotation) # Use this to rotate the figure

plt.tight_layout()

#plt.legend() # Doesn't work yet, bug in matplotlib

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

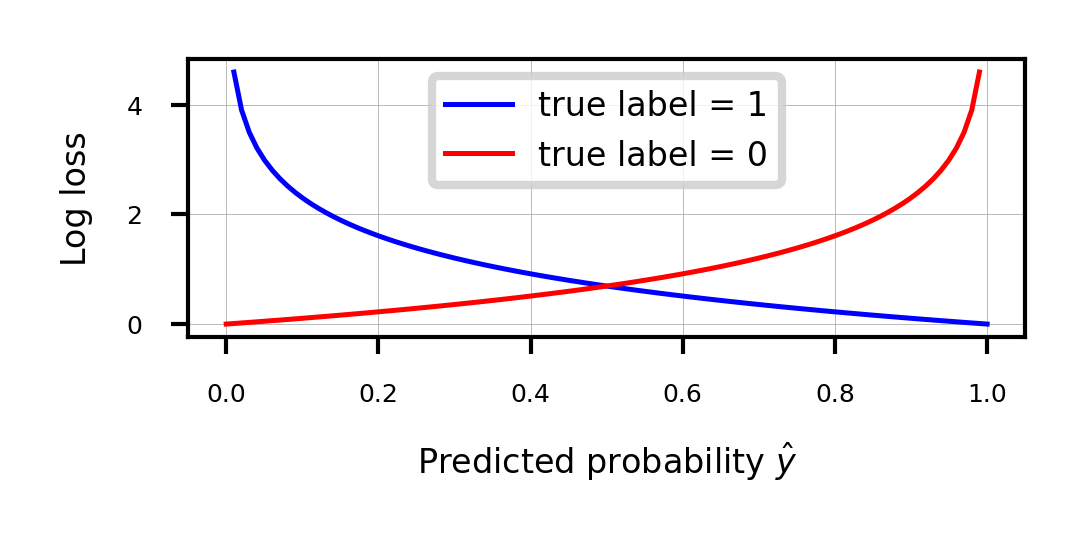

plot_logistic_fit(rotation=150)Loss function: Cross-entropy¶

Models that return class probabilities can use cross-entropy loss

Also known as log loss, logistic loss, or maximum likelihood

Based on true probabilities (0 or 1) and predicted probabilities over instances and classes

Binary case (C=2):

Penalty (a.k.a. ‘surprise’) grows exponentially as difference between and increases

If you are sure of an answer (high ) and it’s wrong (low ), you definitely want to learn

Often used together with L2 (or L1) loss:

Source

def cross_entropy(yHat, y):

if y == 1:

return -np.log(yHat)

else:

return -np.log(1 - yHat)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,2*fig_scale))

x = np.linspace(0,1,100)

ax.plot(x,cross_entropy(x, 1),lw=2*fig_scale,c='b',label='true label = 1', linestyle='-')

ax.plot(x,cross_entropy(x, 0),lw=2*fig_scale,c='r',label='true label = 0', linestyle='-')

ax.set_xlabel(r"Predicted probability $\hat{y}$")

ax.set_ylabel("Log loss")

plt.grid()

plt.legend();

Optimization methods (solvers) for cross-entropy loss¶

Gradient descent (only supports L2 regularization)

Log loss is differentiable, so we can use (stochastic) gradient descent

Variants thereof, e.g. Stochastic Average Gradient (SAG, SAGA)

Coordinate descent (supports both L1 and L2 regularization)

Faster iteration, but may converge more slowly, has issues with saddlepoints

Called

liblinearin sklearn. Can’t run in parallel.

Newton-Rhapson or Newton Conjugate Gradient (only L2):

Uses the Hessian :

Slow for large datasets. Works well if solution space is (near) convex

Quasi-Newton methods (only L2)

Approximate, faster to compute

E.g. Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (

lbfgs)Default in sklearn for Logistic Regression

Some hints on choosing solvers

Data scaling helps convergence, minimizes differences between solvers

In practice¶

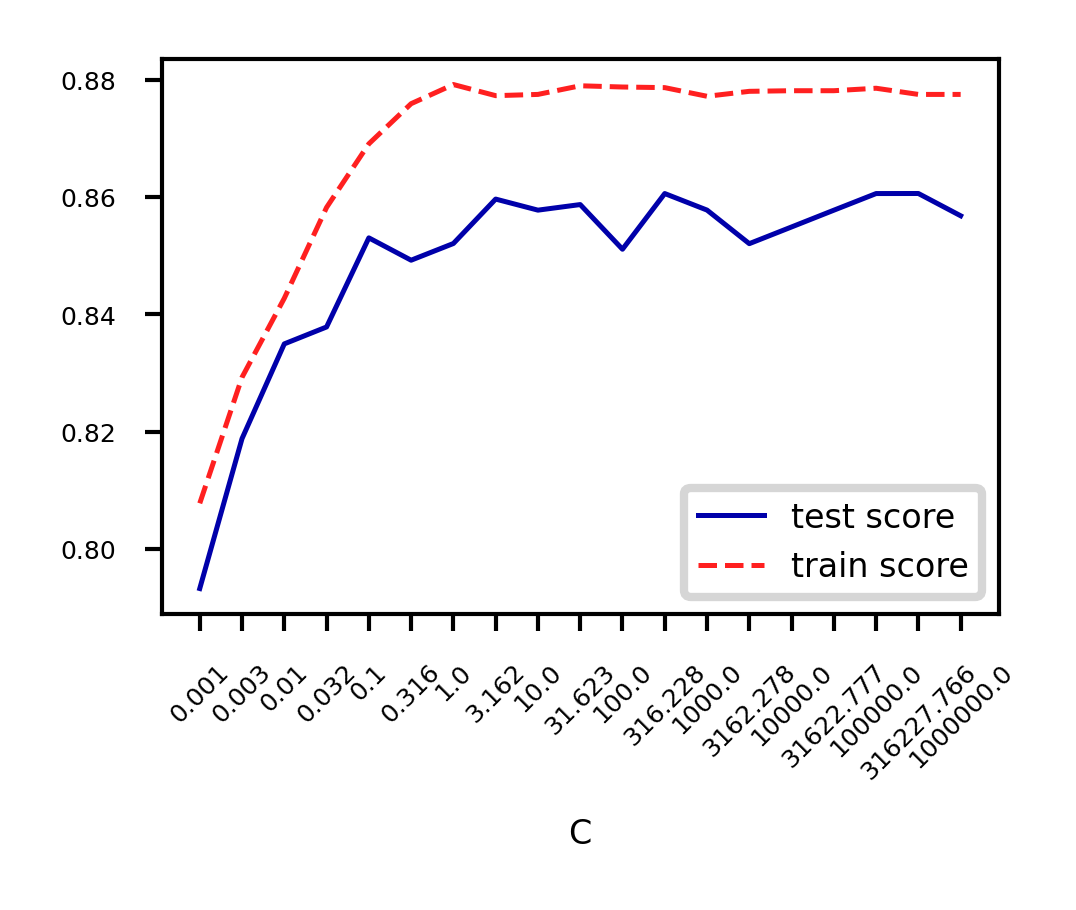

Logistic regression can also be found in

sklearn.linear_model.Chyperparameter is the inverse regularization strength:penalty: type of regularization: L1, L2 (default), Elastic-Net, or Nonesolver: newton-cg, lbfgs (default), liblinear, sag, saga

Increasing C: less regularization, tries to overfit individual points

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

lr = LogisticRegression(C=1).fit(X_train, y_train)Optimization methods (solvers) for cross-entropy loss¶

Gradient descent (only supports L2 regularization)

Log loss is differentiable, so we can use (stochastic) gradient descent

Variants thereof, e.g. Stochastic Average Gradient (SAG, SAGA)

Coordinate descent (supports both L1 and L2 regularization)

Faster iteration, but may converge more slowly, has issues with saddlepoints

Called

liblinearin sklearn. Can’t run in parallel.

Newton-Rhapson or Newton Conjugate Gradient (only L2):

Uses the Hessian :

Slow for large datasets. Works well if solution space is (near) convex

Quasi-Newton methods (only L2)

Approximate, faster to compute

E.g. Limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (

lbfgs)Default in sklearn for Logistic Regression

Some hints on choosing solvers

Data scaling helps convergence, minimizes differences between solvers

Source

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

@interact

def plot_lr(C_log=(-3,4,0.1)):

# Still using artificial data

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,3*fig_scale))

mglearn.discrete_scatter(Xf[:, 0], Xf[:, 1], yf, ax=ax, s=10*fig_scale)

lr = LogisticRegression(C=10**C_log).fit(Xf, yf)

w = lr.coef_[0]

xx = np.linspace(7, 13)

yy = (-w[0] * xx - lr.intercept_[0]) / w[1]

ax.plot(xx, yy, c='k')

ax.set_xticks(())

ax.set_yticks(())

ax.set_title("C = {:.3f}, w1={:.3f}, w2={:.3f}".format(10**C_log,w[0],w[1]))

ax.legend(loc="best");

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_lr(C_log=(4))Analyze behavior on the breast cancer dataset

Underfitting if C is too small, some overfitting if C is too large

We use cross-validation because the dataset is small

Source

from sklearn.datasets import fetch_openml

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_validate

spam_data = fetch_openml(name="qsar-biodeg", as_frame=True)

X_C, y_C = spam_data.data, spam_data.target

C=np.logspace(-3,6,num=19)

test_score=[]

train_score=[]

for c in C:

lr = LogisticRegression(C=c)

scores = cross_validate(lr,X_C,y_C,cv=10, return_train_score=True)

test_score.append(np.mean(scores['test_score']))

train_score.append(np.mean(scores['train_score']))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

ax.set_xticks(range(19))

ax.set_xticklabels(np.round(C,3))

ax.set_xlabel('C')

ax.plot(test_score, lw=2*fig_scale, label='test score')

ax.plot(train_score, lw=2*fig_scale, label='train score')

ax.legend()

plt.xticks(rotation=45);

Again, choose between L1 or L2 regularization (or elastic-net)

Small C overfits, L1 leads to sparse models

Source

X_C_train, X_C_test, y_C_train, y_C_test = train_test_split(X_C, y_C, random_state=0)

@interact

def plot_logreg(C=(0.01,1000.0,0.1), penalty=['l1','l2']):

r = LogisticRegression(C=C, penalty=penalty, solver='liblinear').fit(X_C_train, y_C_train)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,1.9*fig_scale))

ax.plot(r.coef_.T, 'o', markersize=6*fig_scale)

ax.set_title("C: {:.3f}, penalty: {}, score {:.2f} (training score {:.2f})".format(C, penalty, r.score(X_C_test, y_C_test), r.score(X_C_train, y_C_train)),pad=0)

ax.set_xlabel("Coefficient index", labelpad=0)

ax.set_ylabel("Coeff. magnitude", labelpad=0, fontsize=10*fig_scale)

ax.tick_params(axis='both', pad=0)

ax.hlines(0, 40, len(r.coef_)-1)

ax.set_ylim(-10, 10)

ax.set_xlim(0, 40);

plt.tight_layout();

plt.show();Source

if not interactive:

plot_logreg(0.001, 'l2')

plot_logreg(100, 'l2')

plot_logreg(100, 'l1')Ridge Classification¶

Instead of log loss, we can also use ridge loss:

In this case, target values {negative, positive} are converted to {-1,1}

Can be solved similarly to Ridge regression:

Closed form solution (a.k.a. Cholesky)

Gradient descent and variants

E.g. Conjugate Gradient (CG) or Stochastic Average Gradient (SAG,SAGA)

Use Cholesky for smaller datasets, Gradient descent for larger ones

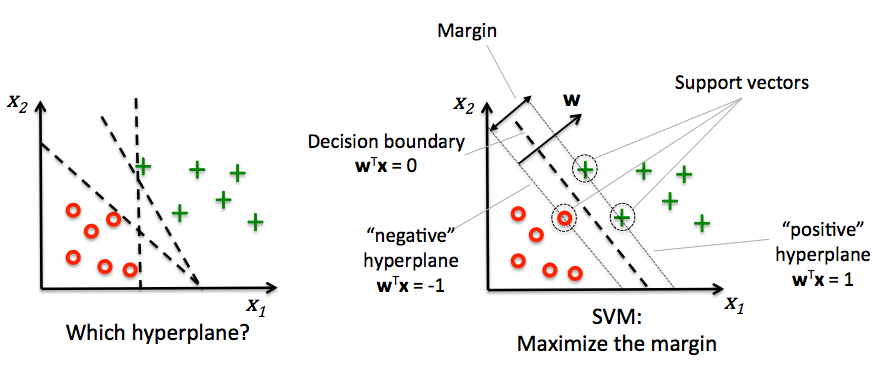

Support vector machines¶

Decision boundaries close to training points may generalize badly

Very similar (nearby) test point are classified as the other class

Choose a boundary that is as far away from training points as possible

The support vectors are the training samples closest to the hyperplane

The margin is the distance between the separating hyperplane and the support vectors

Hence, our objective is to maximize the margin

Solving SVMs with Lagrange Multipliers¶

Imagine a hyperplane (green) that has slope , value ‘+1’ for the positive (red) support vectors, and ‘-1’ for the negative (blue) ones

Margin between the boundary and support vectors is , with

We want to find the weights that maximize . We can also do that by maximizing

Source

from sklearn.svm import SVC

# we create 40 separable points

np.random.seed(0)

sX = np.r_[np.random.randn(20, 2) - [2, 2], np.random.randn(20, 2) + [2, 2]]

sY = [0] * 20 + [1] * 20

# fit the model

s_clf = SVC(kernel='linear')

s_clf.fit(sX, sY)

@interact

def plot_svc_fit(rotationX=(0,20,1),rotationY=(90,180,1)):

# get the separating hyperplane

w = s_clf.coef_[0]

a = -w[0] / w[1]

xx = np.linspace(-5, 5)

yy = a * xx - (s_clf.intercept_[0]) / w[1]

zz = np.linspace(-2, 2, 30)

# plot the parallels to the separating hyperplane that pass through the

# support vectors

b = s_clf.support_vectors_[0]

yy_down = a * xx + (b[1] - a * b[0])

b = s_clf.support_vectors_[-1]

yy_up = a * xx + (b[1] - a * b[0])

# plot the line, the points, and the nearest vectors to the plane

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7*fig_scale,4.5*fig_scale))

ax = plt.axes(projection="3d")

ax.plot3D(xx, yy, [0]*len(xx), 'k-')

ax.plot3D(xx, yy_down, [0]*len(xx), 'k--')

ax.plot3D(xx, yy_up, [0]*len(xx), 'k--')

ax.scatter3D(s_clf.support_vectors_[:, 0], s_clf.support_vectors_[:, 1], [0]*len(s_clf.support_vectors_[:, 0]),

s=85*fig_scale, edgecolors='k', c='w')

ax.scatter3D(sX[:, 0], sX[:, 1], [0]*len(sX[:, 0]), c=sY, cmap=plt.cm.bwr, s=10*fig_scale )

# Planes

XX, YY = np.meshgrid(xx, yy)

if interactive:

ZZ = w[0]*XX+w[1]*YY+clf.intercept_[0]

else: # rescaling (for prints) messes up the Z values

ZZ = w[0]*XX/fig_scale+w[1]*YY/fig_scale+clf.intercept_[0]*fig_scale/2

ax.plot_wireframe(XX, YY, XX*0, rstride=5, cstride=5, alpha=0.3, color='k', label='XY plane')

ax.plot_wireframe(XX, YY, ZZ, rstride=5, cstride=5, alpha=0.3, color='g', label='hyperplane')

ax.set_axis_off()

ax.view_init(rotationX, rotationY) # Use this to rotate the figure

ax.dist = 6

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Source

if not interactive:

plot_svc_fit(9,135)Geometric interpretation¶

We want to maximize (blue contours)

The hyperplane (red) must be for all positive examples:

Find the weights that satify but maximize

Solution¶

A quadratic loss function with linear constraints can be solved with Lagrangian multipliers

This works by assigning a weight (called a dual coefficient) to every data point

They reflect how much individual points influence the weights

The points with non-zero are the support vectors

Next, solve the following Primal objective:

is the correct class for example

so that

It has a Dual formulation as well (See ‘Elements of Statistical Learning’ for the full derivation):

so that

Computes the dual coefficients directly. A number of these are non-zero (sparseness).

Dot product can be interpreted as the closeness between points and

We can replace the dot product with other similarity functions (kernels)

increases if nearby support vectors with high weights have different class

also increases with the number of support vectors and their weights

Can be solved with quadratic programming, e.g. Sequential Minimal Optimization (SMO)

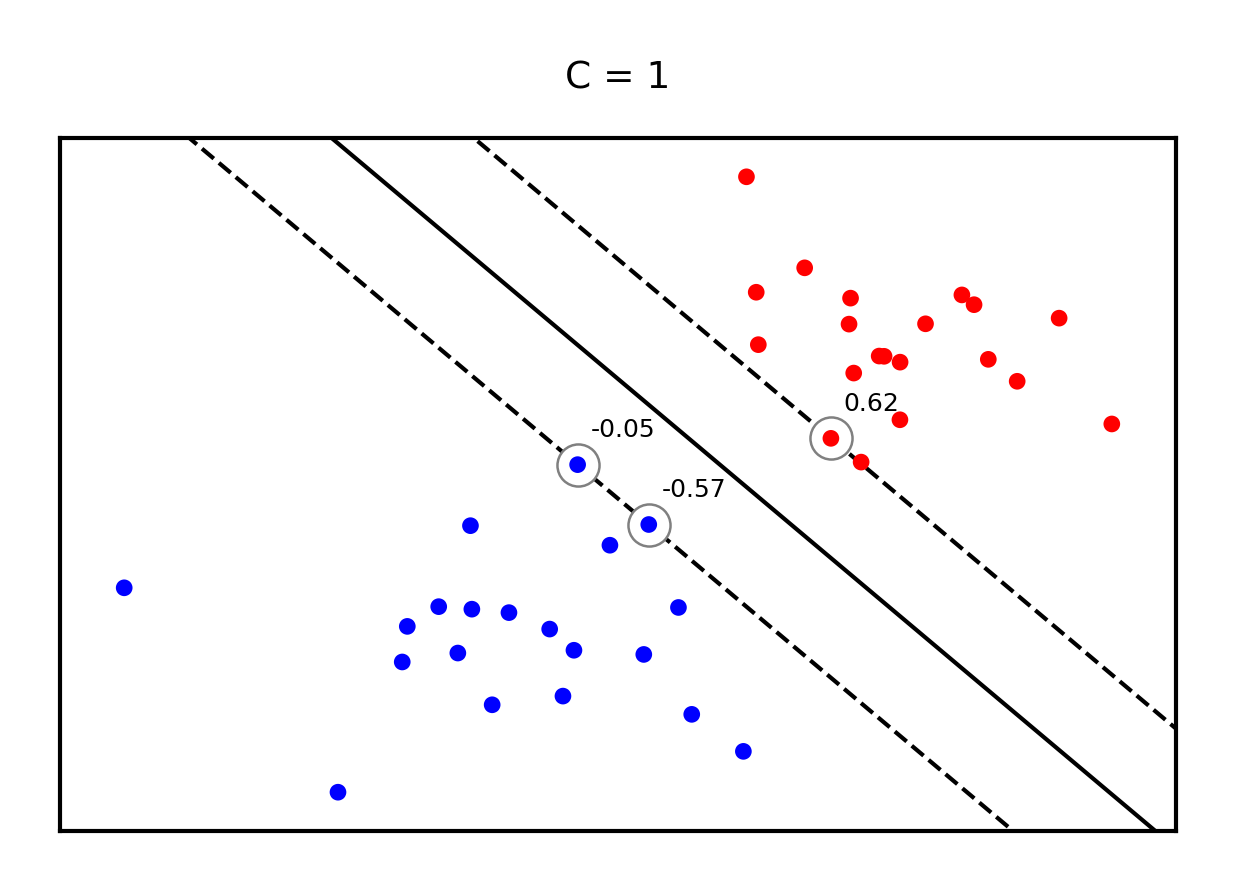

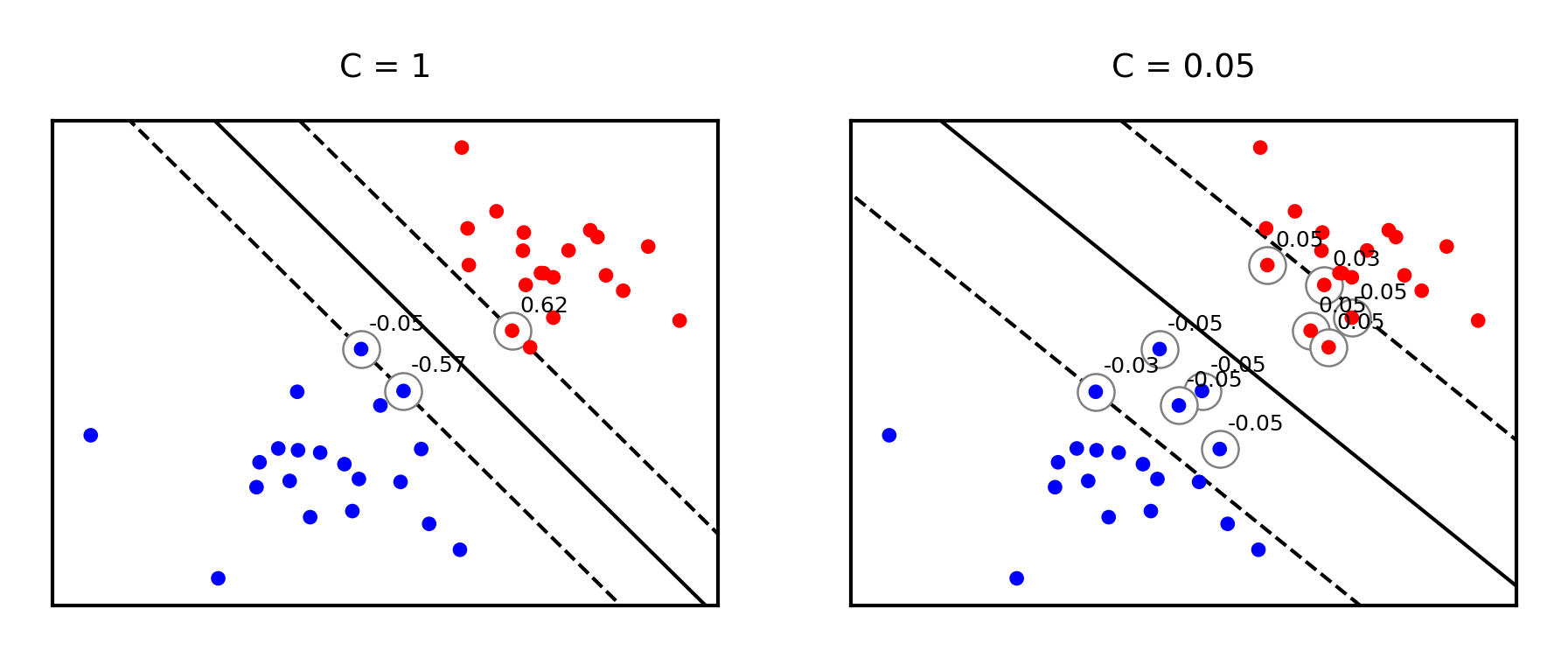

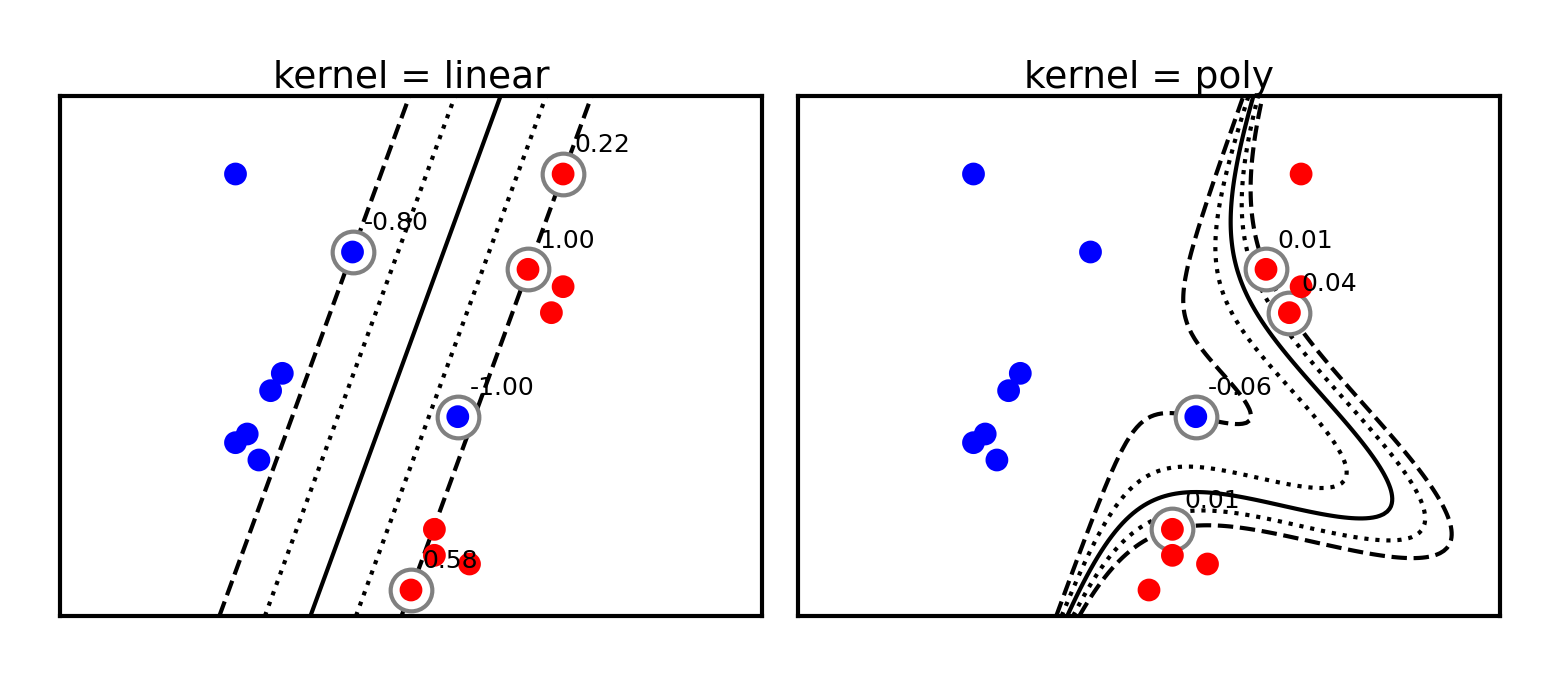

Example result. The circled samples are support vectors, together with their coefficients.

Source

from sklearn.svm import SVC

# Plot SVM support vectors

def plot_linear_svm(X,y,C,ax):

clf = SVC(kernel='linear', C=C)

clf.fit(X, y)

# get the separating hyperplane

w = clf.coef_[0]

a = -w[0] / w[1]

xx = np.linspace(-5, 5)

yy = a * xx - (clf.intercept_[0]) / w[1]

# plot the parallels to the separating hyperplane

yy_down = (-1-w[0]*xx-clf.intercept_[0])/w[1]

yy_up = (1-w[0]*xx-clf.intercept_[0])/w[1]

# plot the line, the points, and the nearest vectors to the plane

ax.set_title('C = %s' % C)

ax.plot(xx, yy, 'k-')

ax.plot(xx, yy_down, 'k--')

ax.plot(xx, yy_up, 'k--')

ax.scatter(clf.support_vectors_[:, 0], clf.support_vectors_[:, 1],

s=85*fig_scale, edgecolors='gray', c='w', zorder=10, lw=1*fig_scale)

ax.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=y, zorder=10, cmap=plt.cm.bwr)

ax.axis('tight')

# Add coefficients

for i, coef in enumerate(clf.dual_coef_[0]):

ax.annotate("%0.2f" % (coef), (clf.support_vectors_[i, 0]+0.1,clf.support_vectors_[i, 1]+0.35), fontsize=10*fig_scale, zorder=11)

ax.set_xlim(np.min(X[:, 0])-0.5, np.max(X[:, 0])+0.5)

ax.set_ylim(np.min(X[:, 1])-0.5, np.max(X[:, 1])+0.5)

ax.set_xticks(())

ax.set_yticks(())

# we create 40 separable points

np.random.seed(0)

svm_X = np.r_[np.random.randn(20, 2) - [2, 2], np.random.randn(20, 2) + [2, 2]]

svm_Y = [0] * 20 + [1] * 20

svm_fig, svm_ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,5*fig_scale))

plot_linear_svm(svm_X,svm_Y,1,svm_ax)

Making predictions¶

will be 0 if the training point lies on the right side of the decision boundary and outside the margin

The training samples for which is not 0 are the support vectors

Hence, the SVM model is completely defined by the support vectors and their dual coefficients (weights)

Knowing the dual coefficients , we can find the weights for the maximal margin separating hyperplane

And we could classify a new sample by looking at the sign of

However, we don’t need to compute to make predictions. We only need to look at the support vectors.

SVMs and kNN¶

Remember, we will classify a new point by looking at the sign of:

Weighted k-nearest neighbor is a generalization of the k-nearest neighbor classifier. It classifies points by evaluating:

Hence: SVM’s predict much the same way as k-NN, only:

They only consider the truly important points (the support vectors): much faster

The number of neighbors is the number of support vectors

The distance function is an inner product of the inputs (or another kernel)

Given , we predict by looking at the classes of the support vectors, weighted by their distance.

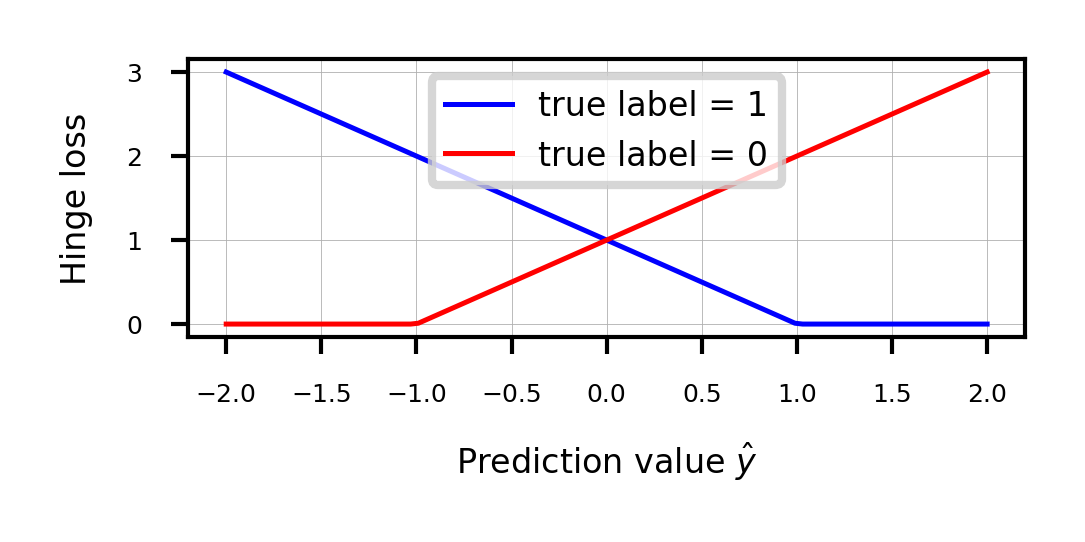

Regularized (soft margin) SVMs¶

If the data is not linearly separable, (hard) margin maximization becomes meaningless

Relax the contraint by allowing an error :

Or (since ):

The sum over all points is called hinge loss:

Attenuating the error component with a hyperparameter , we get the objective

Can still be solved with quadratic programming

Source

def hinge_loss(yHat, y):

if y == 1:

return np.maximum(0,1-yHat)

else:

return np.maximum(0,1+yHat)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,2*fig_scale))

x = np.linspace(-2,2,100)

ax.plot(x,hinge_loss(x, 1),lw=2*fig_scale,c='b',label='true label = 1', linestyle='-')

ax.plot(x,hinge_loss(x, 0),lw=2*fig_scale,c='r',label='true label = 0', linestyle='-')

ax.set_xlabel(r"Prediction value $\hat{y}$")

ax.set_ylabel("Hinge loss")

plt.grid()

plt.legend();

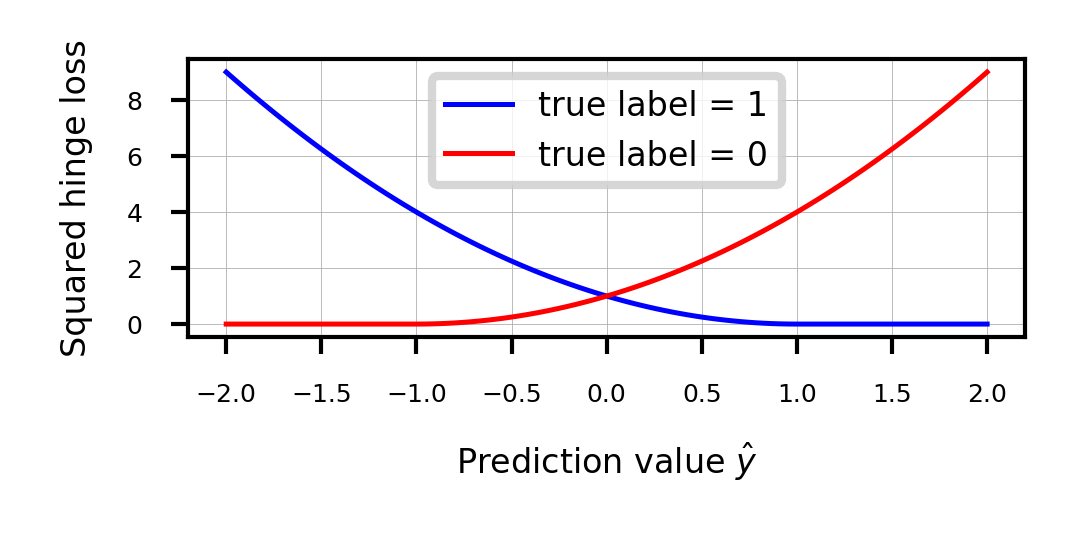

Sidenote: Least Squares SVMs¶

We can also use the squares of all the errors, or squared hinge loss:

This yields the Least Squares SVM objective

Can be solved with Lagrangian Multipliers and a set of linear equations

Still yields support vectors and still allows kernelization

Support vectors are not sparse, but pruning techniques exist

Source

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6*fig_scale,2*fig_scale))

x = np.linspace(-2,2,100)

ax.plot(x,hinge_loss(x, 1)** 2,lw=2*fig_scale,c='b',label='true label = 1', linestyle='-')

ax.plot(x,hinge_loss(x, 0)** 2,lw=2*fig_scale,c='r',label='true label = 0', linestyle='-')

ax.set_xlabel(r"Prediction value $\hat{y}$")

ax.set_ylabel("Squared hinge loss")

plt.grid()

plt.legend();

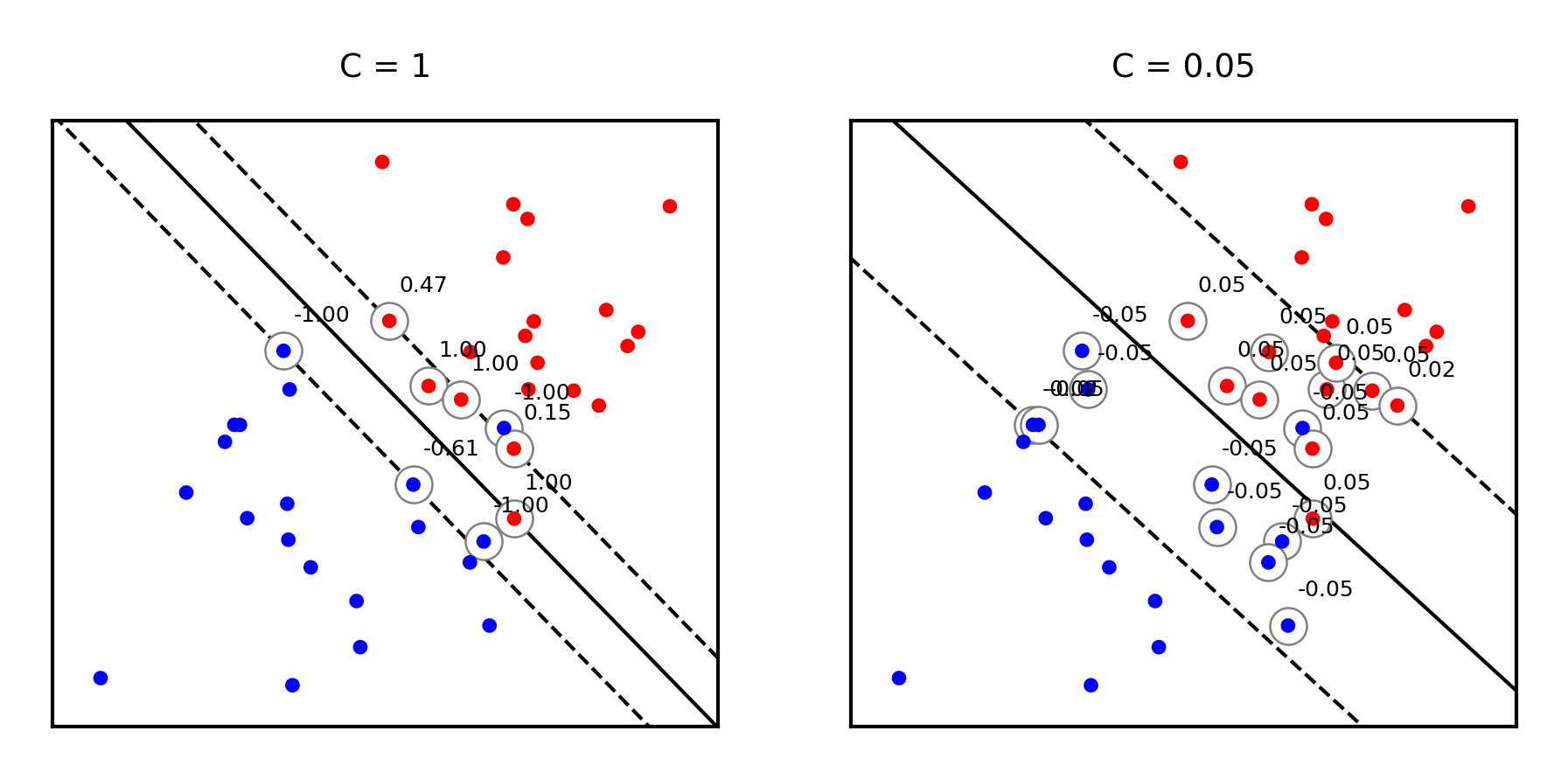

Effect of regularization on margin and support vectors¶

SVM’s Hinge loss acts like L1 regularization, yields sparse models

C is the inverse regularization strength (inverse of in Lasso)

Larger C: fewer support vectors, smaller margin, more overfitting

Smaller C: more support vectors, wider margin, less overfitting

Needs to be tuned carefully to the data

Source

fig, svm_axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(12*fig_scale, 4*fig_scale))

plot_linear_svm(svm_X,svm_Y,1,svm_axes[0])

plot_linear_svm(svm_X,svm_Y,0.05,svm_axes[1])

Same for non-linearly separable data

Source

svm_X = np.r_[np.random.randn(20, 2) - [1, 1], np.random.randn(20, 2) + [1, 1]]

fig, svm_axes = plt.subplots(nrows=1, ncols=2, figsize=(12*fig_scale, 5*fig_scale))

plot_linear_svm(svm_X,svm_Y,1,svm_axes[0])

plot_linear_svm(svm_X,svm_Y,0.05,svm_axes[1])

Large C values can lead to overfitting (e.g. fitting noise), small values can lead to underfitting

Source

mglearn.plots.plot_linear_svc_regularization()

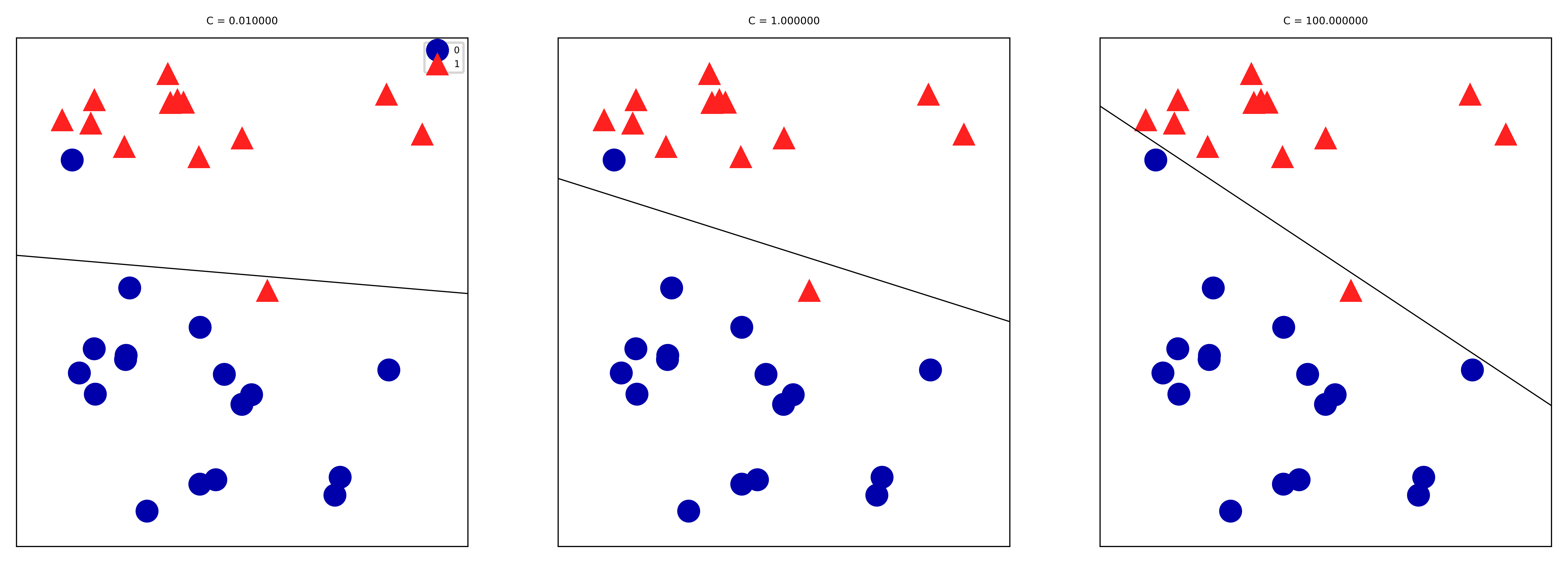

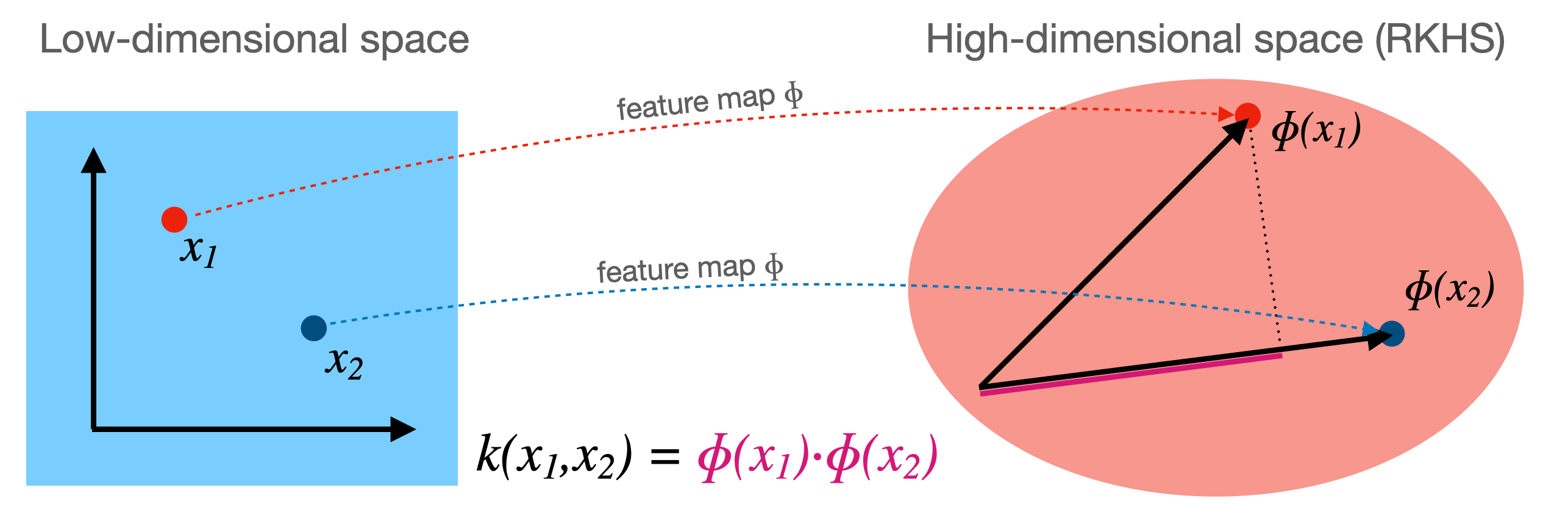

Kernelization¶

Sometimes we can separate the data better by first transforming it to a higher dimensional space

This transformation is called a feature map (but can be expensive)

For certain , we know the function that computes the dot product in :

This kernel function computes the dot product without having to construct (reproduce)

Kernel trick: if your loss function has a dot product, you can simply replace it with a kernel!

For SVMs (in dual form), replacing yields a kernelized SVM:

Polynomial kernel¶

The polynomial kernel (for degree ) reproduces the polynomial feature map

It can be easily computed from the original dot product:

It has two more hyperparameters, but you can usually leave them at default

is a scaling hyperparameter (default )

is a hyperparameter (default 1) to trade off influence of higher-order terms

By simply replacing the dot product with a kernel we can learn non-linear SVMs!

It is technically still linear in , but in our original space the boundary becomes a polynomial curve

Prediction still happens as before, but the influence of each support vector drops of polynomially (with degree )

from sklearn import svm

def plot_svm_kernels(kernels, poly_degree=3, gamma=2, C=1, size=4):

# Our dataset and targets

X = np.c_[(.4, -.7),

(-1.5, -1),

(-1.4, -.9),

(-1.3, -1.2),

(-1.1, -.2),

(-1.2, -.4),

(-.5, 1.2),

(-1.5, 2.1),

(1, 1),

# --

(1.3, .8),

(1.2, .5),

(.2, -2),

(.5, -2.4),

(.2, -2.3),

(0, -2.7),

(1.3, 2.1)].T

Y = [0] * 8 + [1] * 8

# figure number

fig, axes = plt.subplots(-(-len(kernels)//3), min(len(kernels),3), figsize=(min(len(kernels),3)*size*1.2*fig_scale, -(-len(kernels)//3)*size*fig_scale), tight_layout=True)

if len(kernels) == 1:

axes = np.array([axes])

if not isinstance(gamma,list):

gamma = [gamma]*len(kernels)

if not isinstance(C,list):

C = [C]*len(kernels)

# fit the model

for kernel, ax, g, c in zip(kernels,axes.reshape(-1),gamma,C):

clf = svm.SVC(kernel=kernel, gamma=g, C=c, degree=poly_degree)

clf.fit(X, Y)

# plot the line, the points, and the nearest vectors to the plane

if kernel == 'rbf':

ax.set_title(r"kernel = {}, $\gamma$={}, C={}".format(kernel, g, c), pad=0.1)

else:

ax.set_title('kernel = %s' % kernel,pad=0.1)

ax.scatter(clf.support_vectors_[:, 0], clf.support_vectors_[:, 1],

s=25, edgecolors='grey', c='w', zorder=10, linewidths=0.5)

ax.scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], c=Y, zorder=10, cmap=plt.cm.bwr, s=10*fig_scale)

for i, coef in enumerate(clf.dual_coef_[0]):

ax.annotate("%0.2f" % (coef), (clf.support_vectors_[i, 0]+0.1,clf.support_vectors_[i, 1]+0.25), zorder=11, fontsize=3)

ax.axis('tight')

x_min = -3

x_max = 3

y_min = -3

y_max = 3

XX, YY = np.mgrid[x_min:x_max:200j, y_min:y_max:200j]

Z = clf.decision_function(np.c_[XX.ravel(), YY.ravel()])

# Put the result into a color plot

Z = Z.reshape(XX.shape)

#plt.pcolormesh(XX, YY, Z > 0, cmap=plt.cm.bwr, alpha=0.1)

ax.contour(XX, YY, Z, colors=['k', 'k', 'k', 'k', 'k'], linestyles=['--', ':', '-', ':', '--'],

levels=[-1, -0.5, 0, 0.5, 1])

ax.set_xlim(x_min, x_max)

ax.set_ylim(y_min, y_max)

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

plot_svm_kernels(['linear', 'poly'],poly_degree=3,size=3.5)

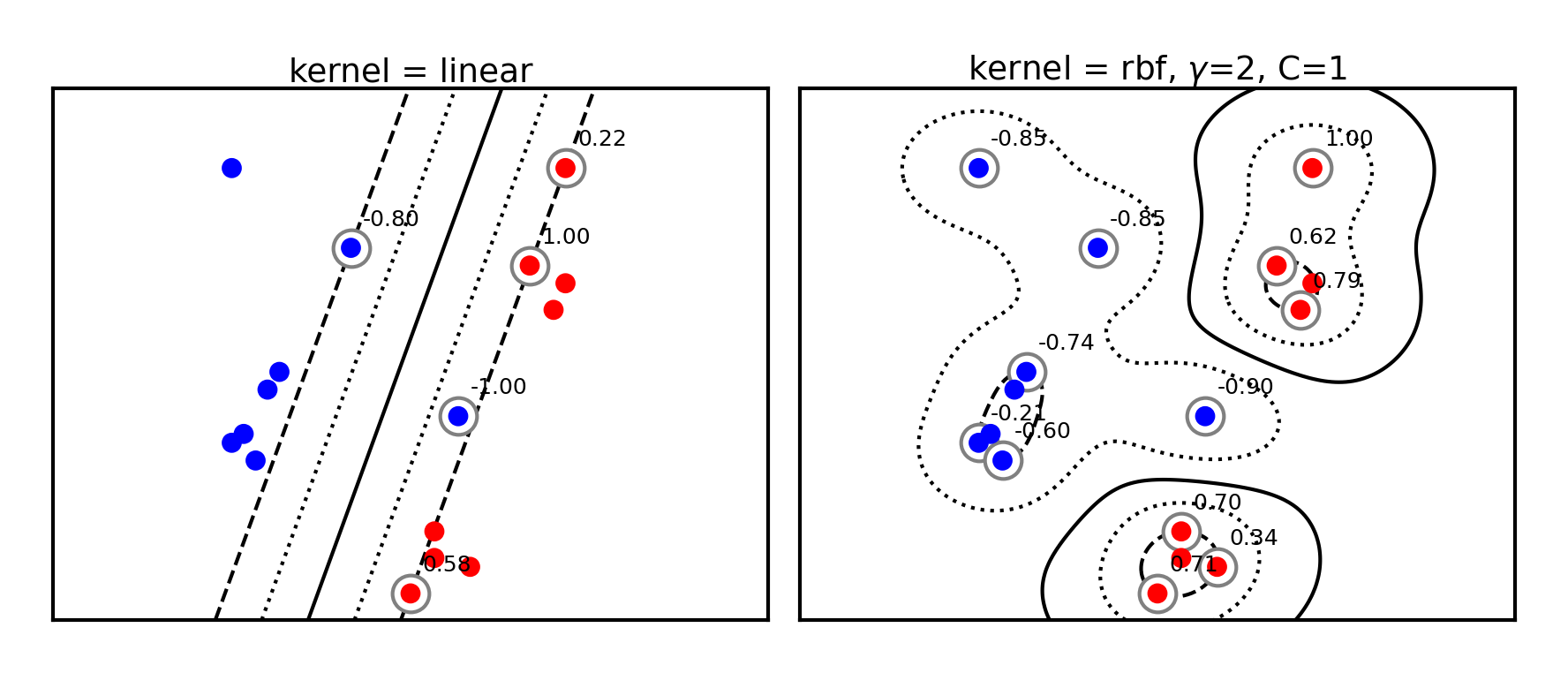

Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel¶

The RBF or Gaussian kernel (of width ) is related to the Taylor series expansion of

It is a function of how closely together two data points are:

The influence of a point on point drops off exponentially with its distance to

The influence of each support vector now drops of exponentially

Hence, predictions are only affected by very nearby support vectors

RBF kernels are therefore called local kernels

plot_svm_kernels(['linear', 'rbf'],poly_degree=3,gamma=2,size=4)

The kernel width () defines how sharply the local influence decays

Acts as a regularizer: low causes underfitting and high causes overfitting

SVM’s C parameter (inverse regularizer) is still at play and thus interacts with

@interact

def plot_rbf_data(gamma=(0.1,10,0.5),C=(0.01,5,0.1)):

plot_svm_kernels(['rbf'],gamma=gamma,C=C,size=5)if not interactive:

plot_svm_kernels(['rbf'],gamma=0.5,C=1,size=5)Kernelization sidenotes (optional)¶

You can invent many more feature maps and corresponding kernels (eg. for text, graphs,...)

However, learning deep learning embeddings from lots of data often works better

You can also kernelize Ridge regression, Logistic regression, Perceptrons, Support Vector Regression,...

The Representer theorem will give you the corresponding loss function

For more detail see the Kernelization lecture under extra materials.

SVMs in scikit-learn¶

svm.LinearSVC: faster for large datasetsAllows choosing between the primal or dual. Primal recommended when >>

Returns

coef_() andintercept_()

svm.SVCallows different kernels to be usedAlso returns

support_vectors_(the support vectors) and thedual_coef_Scales at least quadratically with the number of samples

svm.LinearSVRandsvm.SVRare variants for regression

clf = svm.SVC(kernel='linear') # or 'RBF' or 'Poly'

clf.fit(X, Y)

print("Support vectors:", clf.support_vectors_[:])

print("Coefficients:", clf.dual_coef_[:])Source

from sklearn import svm

# Linearly separable dat

np.random.seed(0)

X = np.r_[np.random.randn(20, 2) - [2, 2], np.random.randn(20, 2) + [2, 2]]

Y = [0] * 20 + [1] * 20

# Fit the model

clf = svm.SVC(kernel='linear')

clf.fit(X, Y)

# Get the support vectors and weights

print("Support vectors:")

print(clf.support_vectors_[:])

print("Coefficients:")

print(clf.dual_coef_[:])Support vectors:

[[-1.021 0.241]

[-0.467 -0.531]

[ 0.951 0.58 ]]

Coefficients:

[[-0.048 -0.569 0.617]]

Solving SVMs with Gradient Descent¶

SVMs can, alternatively, be solved using gradient decent

Good for large datasets, but does not yield support vectors or kernelization

Hinge loss is not differentiable but convex, and has a subgradient:

Can be solved with (stochastic) gradient descent

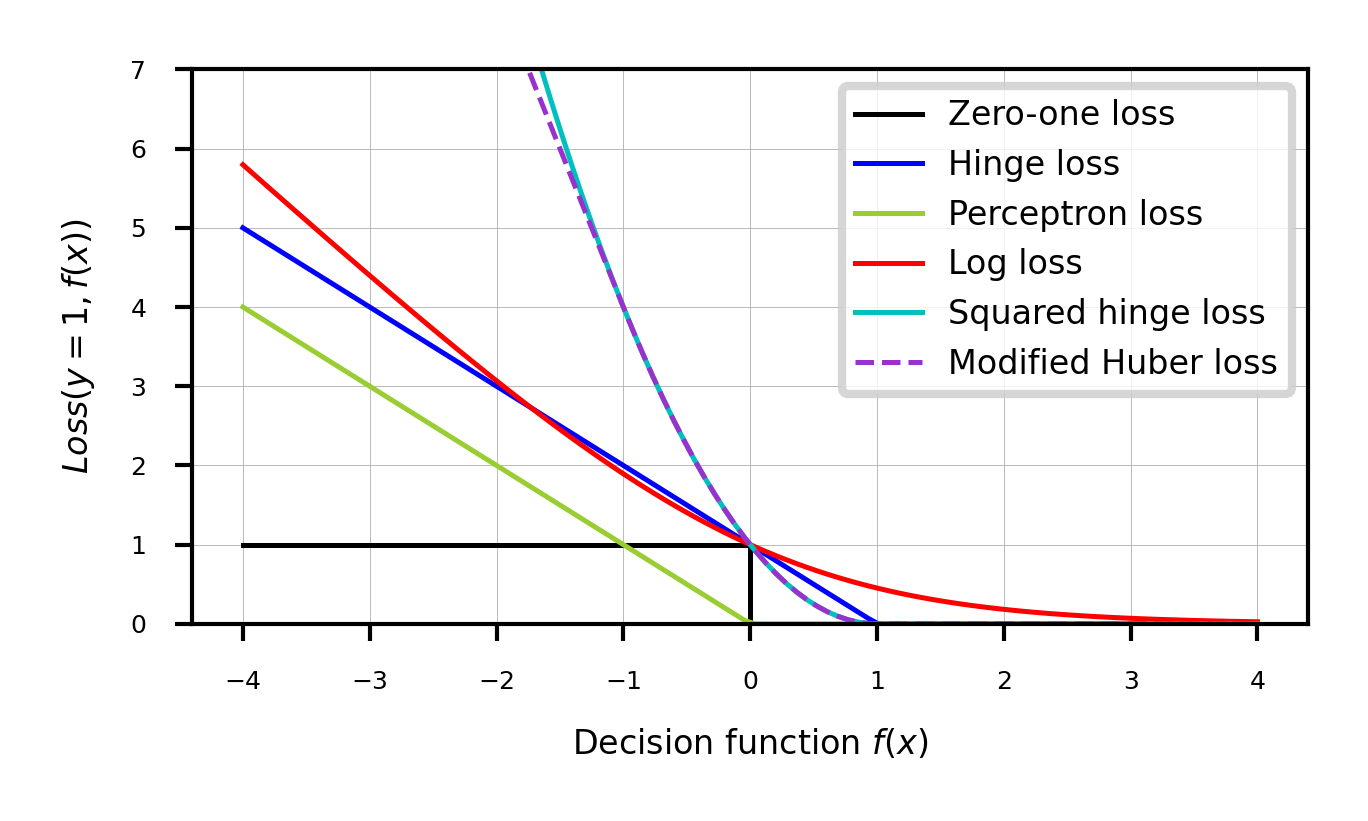

Generalized SVMs¶

There are many smoothed versions of hinge loss:

Squared hinge loss:

Also known as Ridge classification

Least Squares SVM: allows kernelization (using a linear equation solver)

Modified Huber loss: squared hinge, but linear after -1. Robust against outliers

Log loss: equivalent to logistic regression

In sklearn,

SGDClassifiercan be used with any of these. Good for large datasets.

Source

def modified_huber_loss(y_true, y_pred):

z = y_pred * y_true

loss = -4 * z

loss[z >= -1] = (1 - z[z >= -1]) ** 2

loss[z >= 1.] = 0

return loss

xmin, xmax = -4, 4

xx = np.linspace(xmin, xmax, 100)

lw = 2*fig_scale

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8*fig_scale,4*fig_scale))

plt.plot([xmin, 0, 0, xmax], [1, 1, 0, 0], 'k-', lw=lw,

label="Zero-one loss")

plt.plot(xx, np.where(xx < 1, 1 - xx, 0), 'b-', lw=lw,

label="Hinge loss")

plt.plot(xx, -np.minimum(xx, 0), color='yellowgreen', lw=lw,

label="Perceptron loss")

plt.plot(xx, np.log2(1 + np.exp(-xx)), 'r-', lw=lw,

label="Log loss")

plt.plot(xx, np.where(xx < 1, 1 - xx, 0) ** 2, 'c-', lw=lw,

label="Squared hinge loss")

plt.plot(xx, modified_huber_loss(xx, 1), color='darkorchid', lw=lw,

linestyle='--', label="Modified Huber loss")

plt.ylim((0, 7))

plt.legend(loc="upper right")

plt.xlabel(r"Decision function $f(x)$")

plt.ylabel("$Loss(y=1, f(x))$")

plt.grid()

plt.legend();

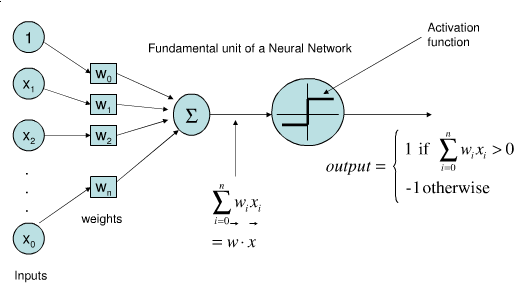

Perceptron¶

Represents a single neuron (node) with inputs , a bias , and output

Each connection has a (synaptic) weight . The node outputs

The activation function (neuron output) is 1 if , -1 otherwise

Idea: Update synapses only on misclassification, correct output by exactly

Weights can be learned with (stochastic) gradient descent and Hinge(0) loss

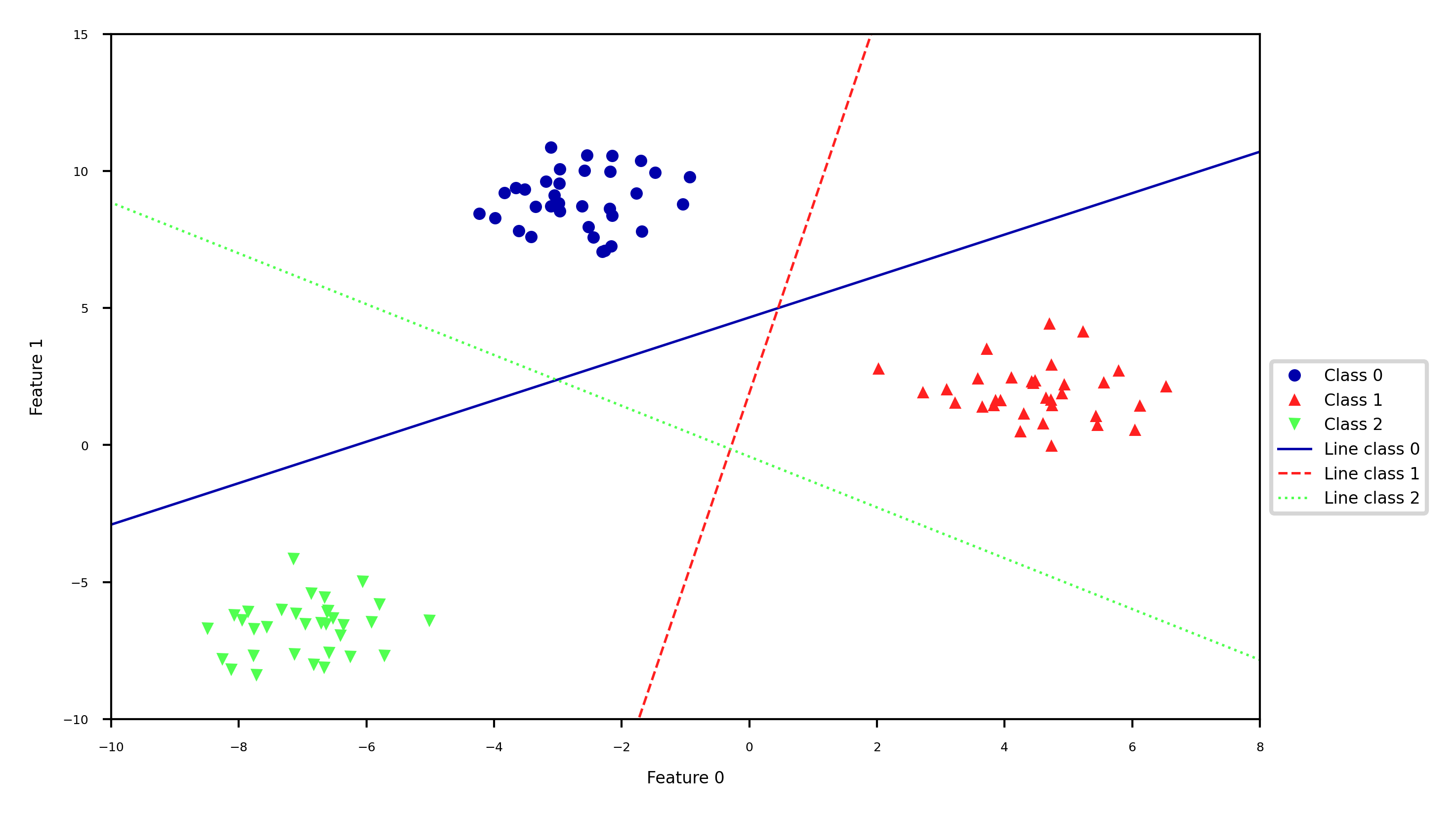

Linear Models for multiclass classification¶

one-vs-rest (aka one-vs-all)¶

Learn a binary model for each class vs. all other classes

Create as many binary models as there are classes

Source

from sklearn.datasets import make_blobs

X, y = make_blobs(random_state=42)

linear_svm = LinearSVC().fit(X, y)

#plt.rcParams["figure.figsize"] = (7*fig_scale,5*fig_scale)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], y, s=10*fig_scale)

line = np.linspace(-15, 15)

for coef, intercept, color in zip(linear_svm.coef_, linear_svm.intercept_,

mglearn.cm3.colors):

plt.plot(line, -(line * coef[0] + intercept) / coef[1], c=color, lw=2*fig_scale)

plt.ylim(-10, 15)

plt.xlim(-10, 8)

plt.xlabel("Feature 0")

plt.ylabel("Feature 1")

plt.legend(['Class 0', 'Class 1', 'Class 2', 'Line class 0', 'Line class 1',

'Line class 2'], loc=(1.01, 0.3));

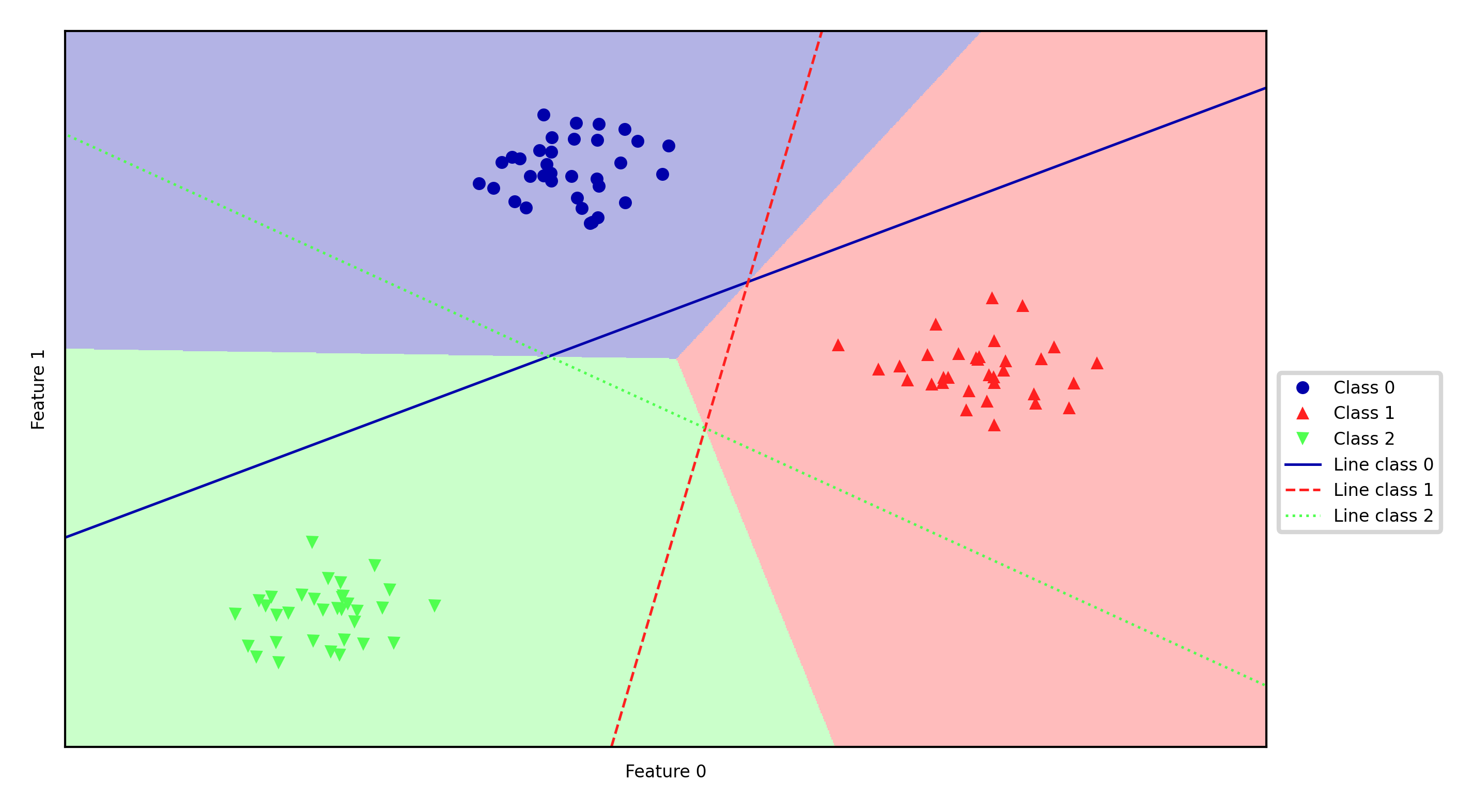

Every binary classifiers makes a prediction, the one with the highest score (>0) wins

Source

mglearn.plots.plot_2d_classification(linear_svm, X, fill=True, alpha=0.3)

mglearn.discrete_scatter(X[:, 0], X[:, 1], y, s=10*fig_scale)

line = np.linspace(-15, 15)

for coef, intercept, color in zip(linear_svm.coef_, linear_svm.intercept_,

mglearn.cm3.colors):

plt.plot(line, -(line * coef[0] + intercept) / coef[1], c=color, lw=2*fig_scale)

plt.legend(['Class 0', 'Class 1', 'Class 2', 'Line class 0', 'Line class 1',

'Line class 2'], loc=(1.01, 0.3))

plt.xlabel("Feature 0")

plt.ylabel("Feature 1");

one-vs-one¶

An alternative is to learn a binary model for every combination of two classes

For classes, this results in binary models

Each point is classified according to a majority vote amongst all models

Can also be a ‘soft vote’: sum up the probabilities (or decision values) for all models. The class with the highest sum wins.

Requires more models than one-vs-rest, but training each one is faster

Only the examples of 2 classes are included in the training data

Recommended for algorithms than learn well on small datasets

Especially SVMs and Gaussian Processes

Source

#%%HTML

#<style>

#td {font-size: 16px}

#th {font-size: 16px}

#.rendered_html table, .rendered_html td, .rendered_html th {

# font-size: 16px;

#}

#</style>Linear models overview¶

| Name | Representation | Loss function | Optimization | Regularization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least squares | Linear function (R) | SSE | CFS or SGD | None |

| Ridge | Linear function (R) | SSE + L2 | CFS or SGD | L2 strength () |

| Lasso | Linear function (R) | SSE + L1 | Coordinate descent | L1 strength () |

| Elastic-Net | Linear function (R) | SSE + L1 + L2 | Coordinate descent | , L1 ratio () |

| SGDRegressor | Linear function (R) | SSE, Huber, -ins,... + L1/L2 | SGD | L1/L2, |

| Logistic regression | Linear function (C) | Log + L1/L2 | SGD, coordinate descent,... | L1/L2, |

| Ridge classification | Linear function (C) | SSE + L2 | CFS or SGD | L2 strength () |

| Linear SVM | Support Vectors | Hinge(1) | Quadratic programming or SGD | Cost (C) |

| Kernelized SVM | Support Vectors | Hinge(1) | Quadratic programming or SGD | Cost (C), ,... |

| Least Squares SVM | Support Vectors | Squared Hinge | Linear equations or SGD | Cost (C) |

| Perceptron | Linear function (C) | Hinge(0) | SGD | None |

| SGDClassifier | Linear function (C) | Log, (Sq.) Hinge, Mod. Huber,... | SGD | L1/L2, |

SSE: Sum of Squared Errors

CFS: Closed-form solution

SGD: (Stochastic) Gradient Descent and variants

(R)egression, (C)lassification

Summary¶

Linear models

Good for very large datasets (scalable)

Good for very high-dimensional data (not for low-dimensional data)

Can be used to fit non-linear or low-dim patterns as well (see later)

Preprocessing: e.g. Polynomial or Poisson transformations

Generalized linear models (kernelization)

Regularization is important. Tune the regularization strength ()

Ridge (L2): Good fit, sometimes sensitive to outliers

Lasso (L1): Sparse models: fewer features, more interpretable, faster

Elastic-Net: Trade-off between both, e.g. for correlated features

Most can be solved by different optimizers (solvers)

Closed form solutions or quadratic/linear solvers for smaller datasets

Gradient descent variants (SGD,CD,SAG,CG,...) for larger ones

Multi-class classification can be done using a one-vs-all approach